Changing Stock-Based Compensation Financial Reporting Solutions: What You Need to Know

Thinking about transitioning to a new provider or platform for stock-based compensation reporting?

We’ve seen a lot of these transitions over the years, both as direct participants and as industry observers. When transitions are managed well, companies quickly unlock new capabilities and efficiency. But when critical elements are left to chance, internal stakeholders feel like they’re stuck in the middle seat of a flight that’s indefinitely delayed.

Migrating to a new stock-based compensation reporting solution can be a high-profile initiative given methodology differences and the potential for a true-up or true-down adjustment to previously-reported financial results. Accounting bugs and unexplained variances can attract the concern of senior leaders. In most cases, and when managed proactively, the adjustment is immaterial—a change in accounting estimate (“change in estimate”) as opposed to the more worrisome change in accounting principle.

Here we discuss our experiences in helping companies change stock-based compensation financial reporting platforms. Whether we’ve been asked to implement our own solution, manage a short-term transition project, or perform emergency surgery on a stalled migration, success hinges on quickly grasping the specific differences between reporting systems, along with how to treat them as part of the provider transition.

Defining a Change in Accounting Estimate

A new solution nearly always requires a one-time adjustment. This adjustment is the difference between the actual life-to-date (LTD) expense you’ve recognized on the old system and the LTD expense that would have been recognized had you been using the new system all along. Typically, this is done for the full population of awards via a point-in-time calculation, whenever the formal transition takes place.

For companies without detailed records of LTD expense, a slightly lower-quality alternative is to compare the remaining unamortized expense. In theory, this is the other side of the same coin, as LTD expense plus unamortized expense should equal the total value of the award. If you go this route, be sure to use the total unamortized expense (i.e. every dollar not expensed) rather than a forfeiture rate-effected number.

Assuming there aren’t any material changes to how awards are being reported, this expense difference is considered a change in accounting estimate. ASC 250-10-45-17 explains how to account for such a change:

A change in accounting estimate shall be accounted for in the period change if the change affects that period only or in the period of change and future periods if the change affects both. A change in accounting estimate shall not be accounted for by restating or retrospectively adjusting amounts reported in financial statements of prior periods or by reporting pro forma amounts for prior periods.

Naturally, companies want to avoid the alternative—a change in accounting principle—since this gives rise to onerous retrospective restatement obligations (see ASC 250-10-45-5). In a provider transition, the case for considering the adjustment a change in estimate gains further support from the way ASC 250, in its glossary, defines a change in accounting principle:

A change from one generally accepted accounting principle to another generally accepted accounting principle when there are two or more generally accepted accounting principles that apply or when the accounting principle formerly used is no longer generally accepted.

A platform transition may yield greater precision, granularity, flexibility, and accuracy. But that doesn’t mean you have to adopt an altogether different generally accepted accounting principle. The usual view is that, within a given principle, there is a spectrum of reasonable ways to arrive at a calculation.

In addition to distinguishing between a change in estimate and change in accounting principle, there’s also the possibility that the transition process uncovers an error. We’ll discuss errors in more detail next.

Data Integrity (Start Here)

The first, and often most important, step in implementing a new financial reporting solution is to ensure the integrity of the data in the new system. This means comparing what goes into the new system with what was in the prior system. Data to reconcile include:

- Total number of awards granted

- Number of shares granted for each award

- Vesting schedules

- Fair values

- Performance multipliers

- Forfeiture rates

Ensuring these inputs are consistent in both systems is the first step to getting reliable reports out of the new system. It’s also easier to explain trickier variances when the underlying data is consistent between systems.

With such a detailed review, expect to catch past issues or inaccuracies in the data. In fact, it’s not a bad idea to treat the review like a “60,000-mile checkup” of your data. Remember, though: If there are major reconciling differences, these could rise to the level of an error. ASC 250-10-45-23 prescribes the same treatment to an error as it does a change in accounting principle, which is a full restatement. ASC 250-10-45-27 applies a customary materiality threshold to errors.

If you’re familiar with system reconciliations, you’ll appreciate the importance of clean comparisons. Key to these are snapshots at the most granular level showing the pre- and post-migration data. Work with the stock plan services department to explain any differences and decide what to do about them. Sometimes the problem isn’t the data at all, but how it was moved from the legacy provider to the new one.

Drivers of Change in Accounting Estimate

Even when the underlying data inputs are the same, two different reporting systems will almost certainly derive slightly different results. It’s best to examine any variance at the grant or tranche level to understand its root cause(s). This is worthwhile even when dealing with large populations of awards, since small percentage variances can add up to a fairly high-dollar impact.

Here are the most common system-related drivers of variance that we see:

| Driver | Consideration |

|---|---|

| Forfeiture Rate Methodology | Different systems deploy different forfeiture rate application methods. Even buzzwords like “dynamic” and “static” forfeiture rate have nuances across providers. For an overview of the different forfeiture rate methodologies, please see our forfeiture rate issue brief.

Many systems apply the popular dynamic forfeiture rate methodology. However, performing the dynamic true-up at the grant level or tranche level of an award can yield markedly different results. |

| Day Count Convention | Some systems begin expensing on the grant date, whereas others begin the day after. Similarly, some expense through the vest date (or applicable requisite service period end date), whereas others finish the day before the vest date. While one day may seem trivial for a tranche that’s vesting over a year or more, the effect adds up across a large population of awards. |

| Amortization Methodology | Textbook examples of straight-line attribution look so simple. But this amortization method is actually much harder to operationalize than the FIN 28 (or “graded”) technique. That’s because it blurs tranches, even though concepts like retirement eligibility, vesting accelerations, and the floor provision must be analyzed at the tranche level.

Therefore, don’t ever assume that two straight-line amortization models will yield the same pattern of expense. In fact, we’ve seen some that follow a “ratable” approach that recognizes the value of each tranche over its own tranche-level service period. While this often gives a similar answer as straight-line amortization, the ratable method is never mentioned in ASC 718 and could cause unacceptable reconciling differences. |

| Floor Provision and Other “Anti-Abuse” Guidance | ASC 718 is filled with niche rules that must accompany the overarching principles. A good example is the floor provision in ASC 718-10-35-3, which stipulates that the expense recognized at any given point in time must at least equal the value of vested shares. The floor provision can interact with the straight-line attribution method in unusual ways.

Front-loaded vesting awards are most affected by the floor provision, as these have more shares vesting upfront. |

| Modifications and Assumed Awards | Modification accounting in ASC 718 is complex. Many providers struggle with it, and end up using highly imperfect shortcuts. If you have modifications, be sure to study how the old and new providers treat them.

Awards assumed during acquisitions pose similar problems. Like modifications, their administration and accounting are often based on imperfect shortcuts. For instance, the number of shares may be reduced by a semi-arbitrary amount to account for the fact that a portion of expense was recognized before the acquisition and shouldn’t be double-counted. (For more about the data considerations of assumed awards, see our Business Combinations White Paper.) |

| Exotic Performance or Other Provisions | Many systems don’t handle exotic performance awards well. For example, multi-metric performance awards or awards with catch-up clauses can be subject to crude workarounds that give rise to a variance when transitioning systems.

The same thing can happen for cases where the service inception date precedes the grant date. For example, clients who have transitioned to using our service often couldn’t begin recognizing expense at the earlier service inception date in the legacy system and, instead, were forced to start expense at grant. |

Two points worth reiterating:

Review expense variances at as granular a level as possible to ensure that large positive and negative variances are not present but simply offsetting one another. It’s easy to gain a false sense of security when the net expense difference is small. In reality, large differences on an absolute basis could be lurking in the background. And if they are, they could yield unpleasant surprises down the road.

Discuss your expense variance analysis with management as well as auditors to ensure everyone is comfortable with the results. Keep in mind that while you and your provider may be experts in these topics, senior management often views stock-based compensation as a black box. Therefore, how you summarize and report the conclusions of your reconciliation process will go a long way to secure understanding and buy-in. Confirm upfront that you can recalculate the values in the new reports, and that any provider you consider has independent calculation reperformance tools for you to use.

Where to Book the Change in Accounting Estimate

Once you’ve locked down the expense difference between the old and new systems as of a chosen time, you’re ready to record the one-time adjusting entry.

While many companies book the change in estimate at the “top of the house,” companies that use direct tracing may elect to push the adjustment down to each segment. Doing so most likely requires calculating the change in estimate at the grant or tranche level in order to accurately map to the segment or cost center, as applicable. Equally important, make sure your segments know the adjustment is coming and what to expect going forward. For instance, moving from a “static” to a “dynamic” forfeiture rate model may create more volatility than segment managers are used to.

Keep in mind that the adjusting expense entry to true-up or true-down expense can be booked as a one-off entry before the new system goes live. Alternatively, you can lump it into the first period of live reporting in the new system.

Extending to EPS, Tax, and Disclosure

In a new system, expense is the first priority for reconciliation. But expense reporting is hardly the only place you’ll see differences in methodology between reporting systems. Earnings per share (EPS) dilution, tax, and disclosure reports all often have slight variation in calculations as well.

One example is the average unrecognized compensation cost (or UCC) component of total proceeds within the treasury stock method (used to calculate diluted EPS). Some systems use a simple two-point average of unrecognized expense at the beginning and end of the period. More sophisticated systems use a daily weighted average to calculate the unrecognized expense.

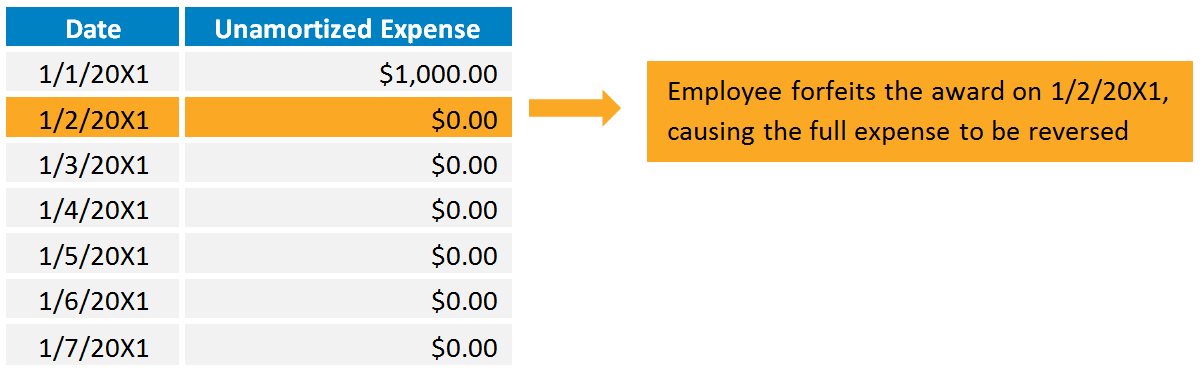

To understand how this difference might have a meaningful impact, let’s look at a very basic scenario. Suppose an award was outstanding at the beginning of the year, but then forfeits on the second day of a seven-day reporting period (thank goodness we don’t have financial closes this frequently!). If a reporting system is applying a two-point average, the UCC for the period will be $500 (($100+$0)/2); however, a daily weighted average calculation would weigh each day equally to calculate the UCC as $142.86 (($100+$0+$0+$0+$0+$0+$0)/7).

The two-point approach versus daily average approach is a common driver of variance in the UCC calculation, but it can also apply to any average number in an EPS report. Most notably, the number of weighted shares outstanding would be much higher under a two-point average in the scenario above. Some of the effects of different approaches will wash out over large populations with frequent activity. However, we constantly see a push for more precision in accounting for share-based compensation.

Tax reporting is affected in a similar way as expense. The deferred tax asset (DTA) balance needs an adjustment entry as a result of the change to expense since the DTA is the tax-affected book expense recognized on unsettled shares.

While DTA is naturally a life-to-date figure, be careful with other tax-related items such as actual tax benefits. It may make more sense to review year-to-date or quarter-to-date activity if older transactions are unreliable or if tax teams have been making adjustments after receiving preliminary figures from the old system. As with any project, even a quick meeting with each of the reporting groups today can prevent considerable headache tomorrow.

Footnote disclosures aren’t as affected by a change of reporting providers. But here, too, you need to know what methodological differences exist between systems. For instance, we’ve seen systems that consider shares which are retirement eligible (or have had expense accelerated because the employee was terminated) as vested for disclosure roll forwards. Another example is assumed awards, where one system lumps them with actual new grants and the other system puts them on a separate line item.

Dealing with Very Large Variances

While under the hood (so to speak), you may spot such a major difference in variance that resolving it could be construed as a change in accounting principle.

Improbable though this is, you should consider it when encountering very large variances. Whatever determination you make, document it thoroughly in case you need to revisit it later.

Wrap Up

Some providers are more helpful than others in carrying out a transition. Our view is that the service provider must play a major role in any reconciliation exercise because they know their system best. One of the top reasons behind failed implementations is an inability to reconcile why the legacy system is producing a different cumulative expense amount than the new system. Getting to the root of the problem requires working with granular datasets and drilling into accounting methodology conventions.

While this article is by no means an exhaustive “how-to” guide, it captures some of the techniques we believe are essential in a transition and that have worked well in our client work. We invite you to reach out with questions and thoughts as they arise.

Don’t miss another topic! Get insights about HR advisory, financial reporting, and valuation directly via email:

subscribe