Incentive Stock Option Accounting and Strategy Considerations

Pre-IPO and newly public companies are the most prevalent granters of employee stock options.[1] These awards create an opportunity for significant upside. Not only that, one flavor—the incentive stock option (ISO) as defined in Section 422 of the Internal Revenue Code—also confers favorable tax treatment to the recipient.

This article is part of a broader series on pre-IPO equity compensation and how companies navigate compensation strategy and financial reporting decisions. Here we focus on the decision to grant incentive stock options, including why they’re attractive and, more importantly, the complications companies face when accounting for ISOs.

Background

ISOs are attractive equity instruments for employees due to the preferential tax treatment. Employees aren’t taxed on their ISOs until the day they sell them. They also benefit from lower long-term capital gains tax rates if they hold the stock for the required period of time (one year from the exercise date and two years from the grant date).

Early-stage pre-IPO companies tend to favor ISOs because the preferential tax treatment can be extremely valuable to employees. Imagine receiving options on stock that starts out at $0.50, appreciates at a significant multiple by some eventual IPO date, and leaves you owing tax on that appreciation only at the long-term capital gains tax rate instead of at the ordinary income rate. To make matters more pragmatic, the issuing company is most likely unprofitable, meaning it doesn’t need the corporate tax deduction it misses out on by granting ISOs.

As pre-IPO companies mature and progress toward an eventual liquidity event, you’ll tend to see ISO granting prevalence levels decrease. There are many reasons. One is a desire to capture the corporate tax deduction. Another is to reduce the administrative headaches of ISOs. A third is the view that employees will prioritize liquidity over favorable tax treatment—that is, they’ll violate the ISO rules and voluntarily give up taxation at the long-term capital gains rate. Nonetheless, even when companies transition away from granting ISOs, they must still track and account for outstanding ISOs.

What’s our view? We think it’s valuable to offer tax-efficient equity vehicles, especially at early stages in an organization’s life. This is also why you see 83(b) elections at these same early stages. We focus on the complexities of ISOs in this article not to dissuade their use, but to highlight the issues that need to be managed so you can plan accordingly. In our experience, proper planning and administration allows effective ISO granting during a pivotal period in the organization’s scaling journey.

ISO $100K Limit

ISOs have many limiting conditions, a particularly important one being what’s called the $100k limit. That is, the aggregate grant date fair market value of ISOs that become exercisable for an employee cannot exceed $100,000 in any calendar year, as noted in Internal Revenue Code Section 422(d). If the value exceeds that limit, the excess amount that becomes exercisable in the calendar year loses its preferential tax benefit, effectively turning into a non-qualified stock option (NSO). To ensure proper tax treatment and tracking, companies often split the original award into ISO and NSO portions, which can be administratively difficult.

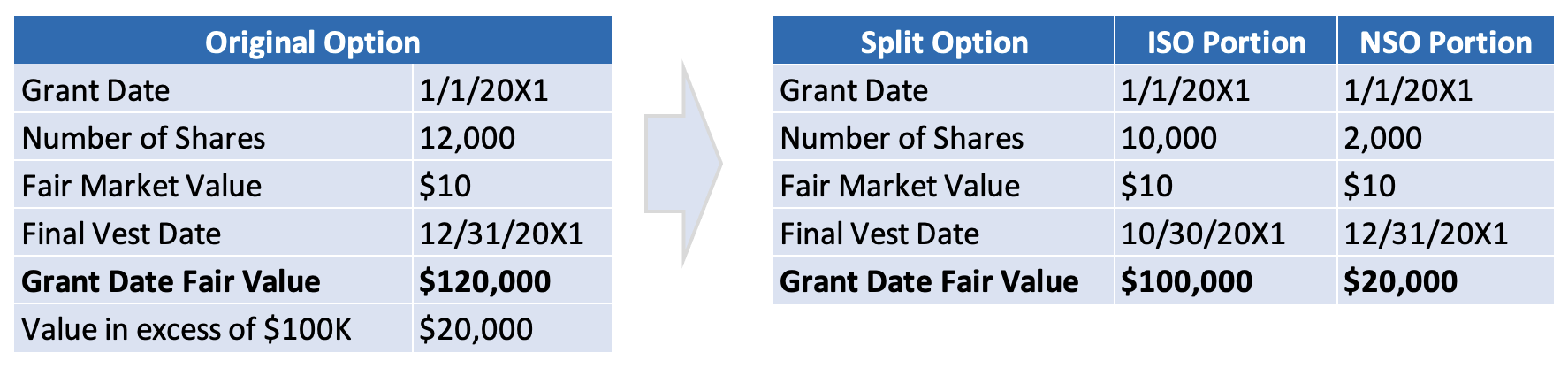

Let’s consider an example. On 1/1/20X1, employee A is awarded 12,000 ISOs with a grant date fair market value and a strike price of $10. The award has a monthly vesting schedule with a vest end date on 12/31/20X1. As a result, there will be a total grant date fair market value of $120,000 exercisable in 20X1, $20,000 above the $100,000 limit.

To properly track the tax treatment for this award, the company will classify $100,000 of the award as ISOs and the remaining $20,000 as NSOs. This is achieved by artificially splitting the award into two different awards. The two awards have the same grant date and strike price, but different vesting schedules. Table 1 shows how the award is bifurcated.

Due to this split, the administration system now shows that employee A received two separate awards, one with an award type of ISO and one with an award type of NSO. There are several administration and reporting considerations to be aware of when accounting for these split awards, especially when it comes to stock administration, valuation, expense recognition, tax, and financial statement disclosure. Let’s discuss these considerations in detail.

Stock Administration Considerations

Most stock administration systems have matured to handle the dynamics of ISO/NSO splits, leaving primary complexity with the accounting. Nevertheless, HR and legal need to ensure the stock system is correctly implemented to result in a smooth participant experience. As ISO/NSO splits are implemented, you need to consider all ISOs that are becoming exercisable in the year. If there are multiple grants resulting in exercisable ISOs in a particular year, the aggregate amount needs to be referenced when performing the split. This could cut across multiple grants, giving rise to participant confusion.

One reason the ISO split confuses participants is the tax treatment. Since ISOs that breach the $100,000 watermark are converted to NSOs, they’re consequentially taxed like NSOs. Participants may be surprised as they see tax withholding taking place on the newly created NSOs. Another complication to navigate is how a cancellation event, acceleration, vesting modification, or leave of absence influences the application of the $100,000 rule. Cancellations will pull exercisable shares off the table, therefore reducing shares converted to NSOs. Accelerations are likely to do the opposite. Leaves of absence usually freeze the vesting schedule, but this will depend on the specific plan rules.

One specific challenge to highlight is related to mergers and acquisitions. Many merger agreements allow for accelerations upon a change in control. In that case, when an acquisition occurs, some or all of the unvested options are accelerated. In practice, the acquirer generally only assumes the outstanding options, and thus the vested and exercised options won’t be loaded into the acquirer’s administration system before the acquisition. But those vested and exercised options need to be taken into consideration when determining the $100K limit when the outstanding ISOs are accelerated. When that happens, additional steps are required to split the outstanding ISO awards correctly. Assumed options with double-trigger provisions will also add complexity given the shares will be accelerated and become exercisable upon termination events, which potentially requires more ISOs to be converted into NSOs.

Valuation Considerations

Stock options are generally valued using the Black-Scholes-Merton (BSM) formula. One of the key inputs into this model is the expected term, which is an estimate of when the employee will exercise. When the option is split into two portions (ISO and NSO), companies should be careful not to value them separately even though they’re presented as two different awards in the stock administration system. While conceptually the split may influence exercise behavior and exercise sequencing decisions, adequate historical data to prove this is rarely available.

In our experience reviewing ISO/NQ setups, we occasionally see different valuations between the split award types. But when drilling into the reason, we don’t find empirical support or a deliberate valuation premise for assigning different values. Instead, it’s because the system inadvertently applied different assumptions as a result of the differential vesting schedules.

Using the same example as earlier, the expected term for the ISO portion would theoretically be shorter than the NSO portion since the time to vest is shorter (i.e., 10 months at the longest for the ISOs and 12 months at the longest for the NSOs). If companies use default tools in the reporting system to value these options, they may inadvertently apply different fair values to each portion of the option due to the differences in expected terms. However, insofar as legacy “term-from-vest” expected term estimation methods have lost their appeal, the most common practice is to apply an aggregate expected term assumption to the entire award.

For simplicity and given data limitations, the two award components are generally given the same fair value. Arriving at this outcome may require workarounds and careful modeling to avoid unintended outcomes.

Expense Calculations

Similar to the valuation treatment, the total grant date fair value of the ISO and NSO portions of the option should be amortized as if they were a single combined award. At the end of the day, the employee was granted a single award that was artificially split for tax reasons. As noted, the ISO/NSO split grants are commonly shown as two separate awards granted on the same grant date, with separate vesting schedules depending on when the $100K limit is hit.

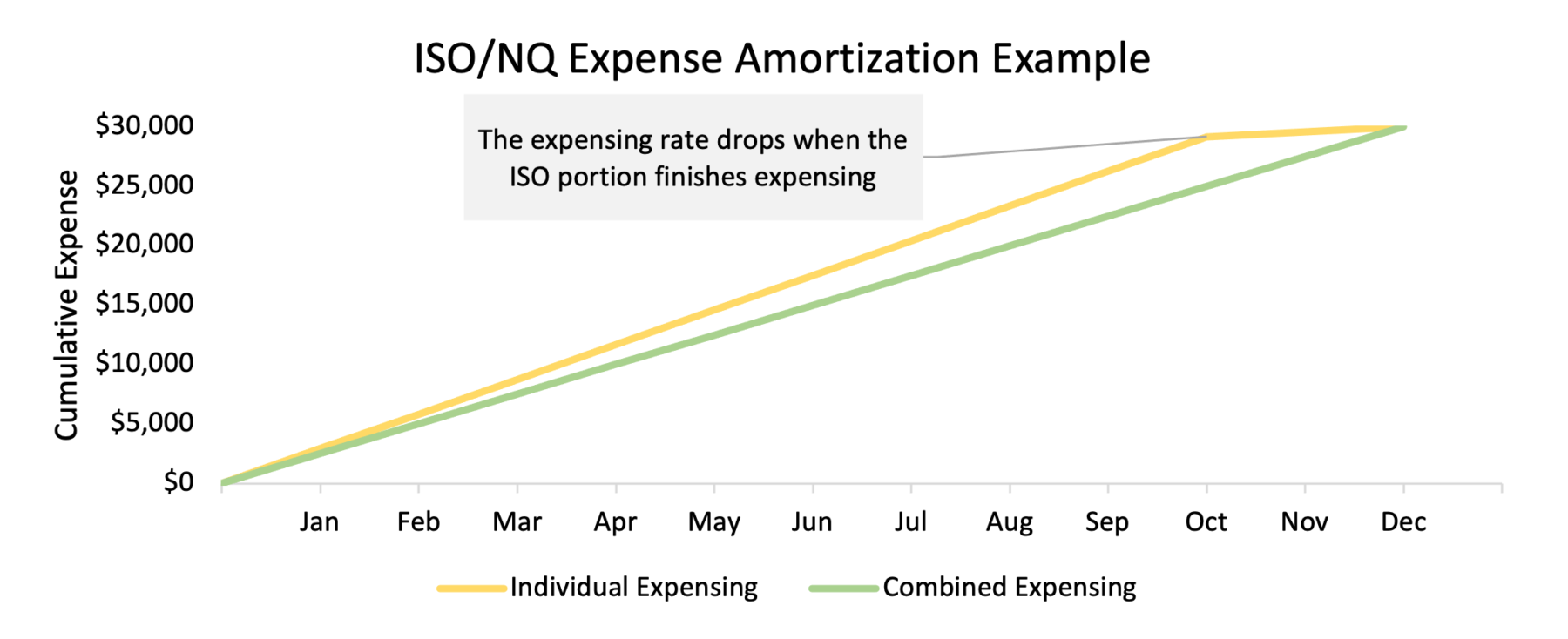

Use caution when using standard expense reports from off-the-shelf financial reporting software tools. Such tools may assume that both portions of the awards will start expensing from the grant date to the respective vest dates. This would result in frontloading expense, with more expense being recognized earlier in the vesting life—rather than straightlining expense for the combined award over the full life of the award. Figure 1 illustrates this risk.

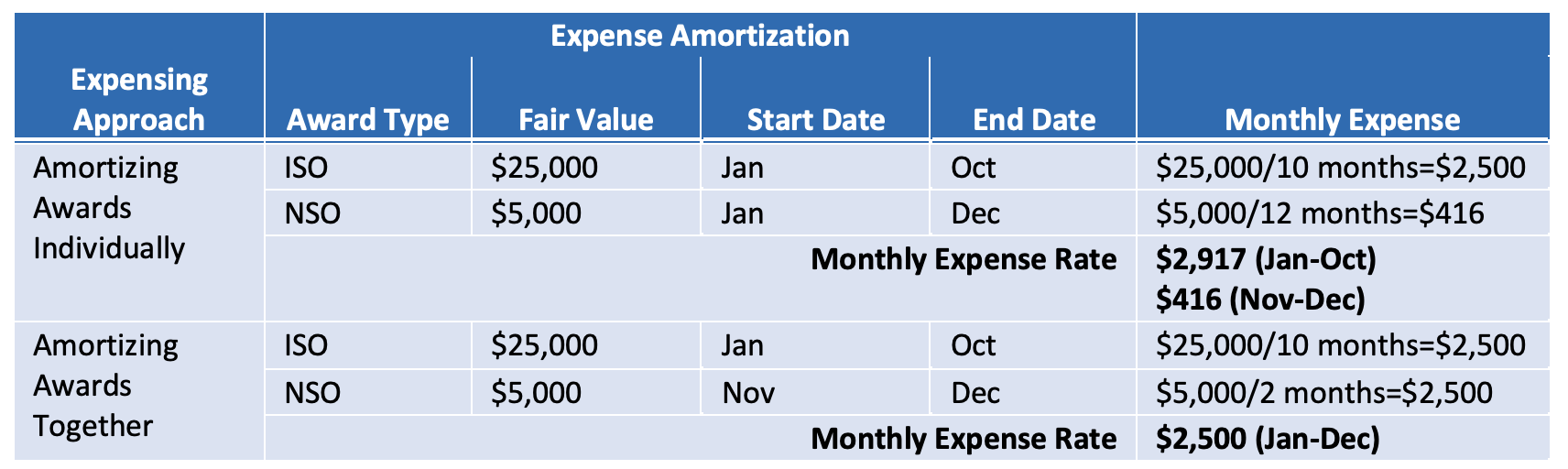

To illustrate further, let’s dive deeper into the calculations. Assume that the total grant date fair value of the award using the BSM formula is $30,000 (not to be confused with the grant date fair market value, which is based off the stock price at grant). The expensing methodology will result in different monthly expense amounts, as shown in Table 2.

In some financial reporting systems, companies may be able to fix the expense pattern problem by overriding the service inception date (also known as the expense start date) for the NSO portion. However, it can be a manual and burdensome process given that awards can be split in various ways. Let’s look at a more complex award example in Table 3.

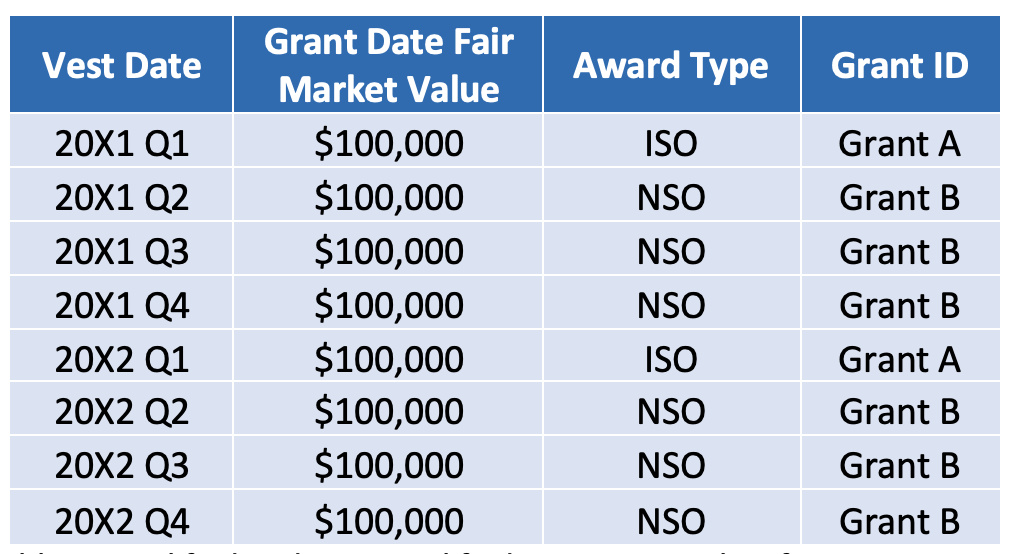

This first tranche of the award is qualified for the preferential tax treatment while the remaining tranches vesting in the current year become non-qualified. Then the following year, the $100,000 limitation resets for another tranche, and the remaining tranches are again classified as NSOs.

In this case, we need to analyze the expensing start and end date for each vesting tranche to preserve the straight-line expense. For instance, the 20X2 Q1 tranche should not start expensing when the previous tranche of the award (i.e., the Q1 20X1 tranche) vests. Instead, the expense should commence when the Q4 2021 tranche vests.

The process gets even more complicated when companies grant awards that vest monthly over four years, and there are 48 tranches to review for each award. That’s not to mention the possibility that employees may have multiple awards granted over time. Therefore, automation is critical in reducing manual errors when modifying the service inception date for awards with multiple tranches.

Implications from Early Exercises

To deliver even more potential tax benefits, some companies may allow employees to exercise their options before they vest, common referred to as an “early exercise” provision. The early exercised shares will apply toward the $100,000 limit and may result in an ISO/NSO split. Additionally, the $100,000 limit is based on the total value exercisable to an employee in any given year, not by the award. Therefore, if the employee has other ISO awards vesting in the same year, early exercising the new ISO award may result in the whole award being converted to an NSO.

Tax Reporting Complexities

Although the ISO and NSO components of the award are valued and amortized as a single award, they should be tracked separately due to the different tax treatments we’ve been highlighting. For an employee to receive the tax advantages of an ISO, its sale must be made at least two years after the grant date and one year after exercise. If the shares are sold before the holding period requirements are met, then a disqualifying disposition event occurs.

Companies cannot realize a tax benefit on ISO exercises as long as the holding requirements are met. Therefore, companies generally don’t set up a deferred tax asset (DTA) balance for the ISO component. However, when a disqualifying disposition event for the ISO component occurs, the employee recognizes ordinary income and the company realizes a tax benefit similar to that on a normal NSO. Generally, the amount of income and tax benefit realized is based on the spread at the time of exercise (i.e., the difference between the exercise date stock price and strike price). However, if the shares are sold at a price less than the exercise date stock price, then the tax benefit is limited to the difference between strike price and sale date stock price, per IRC 422(c).

Using the initial award example, the company would begin building up the DTA balance when the NSO portion of the award starts expensing on November 1, 20X1. At the end of 20X1, there would a be gross DTA balance of $5,000 for the award. The $25,000 of expense relating to the ISO portion of the award would result in a permanent difference.

Disclosure Requirements

There are several considerations for footnote disclosures. First, consistent with the expense calculation, the remaining expensing life of awards should reflect the combined ISO and NSO components. Many financial reporting systems lack the capability to calculate expense life based on the combined award, so manual calculations are required.

In addition, as we mentioned in the valuation section, the disclosed fair value and the underlying BSM assumptions should reflect the single set of shares issued with the same expected term and other attributes. Finally, it’s generally better to disclose ISOs and NSOs together since their valuation and expense amortization are performed together.

Summary

ISO granting has immense benefits, especially at early stages in the pre-IPO lifecycle. Even if employees ultimately choose liquidity over favorable tax treatment, the message to recruits that the company grants tax-efficient stock options is powerful. As practice has it, many companies eventually navigate from ISOs to NSOs (and then away from options altogether).

We focused on the challenges of ISO granting because they span stock administration, corporate accounting, and tax. Cross-functional challenges can be deterrents, but our experience is that these ISO complexities are manageable if you plan for them upfront.

When relying on off-the-shelf financial reporting software tools, it’s critical to understand what additional overrides are needed to ensure that the proper valuation and reporting methodologies are being applied. Take close inventory of the system limitations and what expectations are transferred to the user(s).

We’ve helped many companies automate and streamline how they split ISOs into a tax advantaged portion and a non-qualified portion. We’ve also assisted companies in ensuring that the expensing, valuation, disclosure, and tax reporting considerations and complexities are appropriately accounted for through automation. If you have any questions, please don’t hesitate to contact us.

[1] Many mature public companies continue to grant employee stock options even though stock options are less prevalent than they were in the early 2000s. There are pros and cons to using stock options as a mature company, but we don’t cover these in this article.