Non-GAAP Metrics and Their Dual Intersection with Stock-Based Compensation, Part 2: The Role of Non-GAAP Metrics in Executive Compensation

This is the second installment of our 2022 series on non-GAAP earnings metrics. Although a widely researched topic, non-GAAP earnings measures have a special tie-in to stock-based compensation (SBC). Not only is SBC expense a controversial and popular non-GAAP adjustment in earnings releases,[1] but non-GAAP metrics are widely used in executive compensation performance awards.[2]

In the first installment, we looked at the investor side and prevalence levels of companies excluding SBC expense in formulating non-GAAP earnings metrics to investors (“the Street”). In this edition, we shift gears to the executive compensation side and look at how decisions are made in setting performance metrics that are based on non-GAAP earnings formulations.

That includes leveraging our proprietary dataset to share prevalence levels for the various potential exclusions used to set a non-GAAP performance metric. We also explore why some seemingly benign metrics have low prevalence levels and what this says about the distinction between compensation committee discretion and the use of formalized non-GAAP performance measures.

From there, we’ll turn to the question of whether there’s symmetry in the specific non-GAAP metrics companies use in their earnings releases and those used in their executive compensation programs. We’ll conclude with considerations for compensation leaders as they make decisions on which non-GAAP metrics to adopt.

**************

About the Research

This series is based on a sample of 200 companies from a hand-collected database. Companies were selected randomly but with a constraint to ensure representation across all 12 economic sectors. Data on non-GAAP street earnings metrics is from each company’s most recent earnings release (late 2021 or early 2022). Data on how non-GAAP earnings are used in executive compensation arrangements is from each company’s most recent proxy (usually 2021).

**************

Non-GAAP Metrics Used in Executive Compensation

We began our analysis by filtering our dataset for companies that issue performance-based awards with a financial metric. Stock option granters or companies with only a total shareholder return (TSR) metric won’t have non-GAAP executive compensation metrics since options and TSR awards only reference share price performance.

The most common exclusions in non-GAAP street earnings are often different from the non-GAAP exclusions used in executive compensation performance metric design. This is largely due to the different objectives of each measurement.

In executive compensation, circumstances can change in unpredictable ways during the typical three-year performance period, making the original goals irrelevant. The classic example is a change in tax law or accounting standards. If performance goals are set in 20X2 and a tax law change goes live in 20X3, the original goals simply may not make any sense if their determination was predicated on a different tax regime. As such, a measure of earnings that excludes the impact of a tax law (or accounting standard) change would be appropriate.

It’s also important to avoid incentive designs that inadvertently encourage harmful shareholder outcomes. For example, if divesting a business unit is good for the company but would result in a one-time drop in earnings, executives’ performance awards shouldn’t introduce an implicit penalty for making the right shareholder decision.

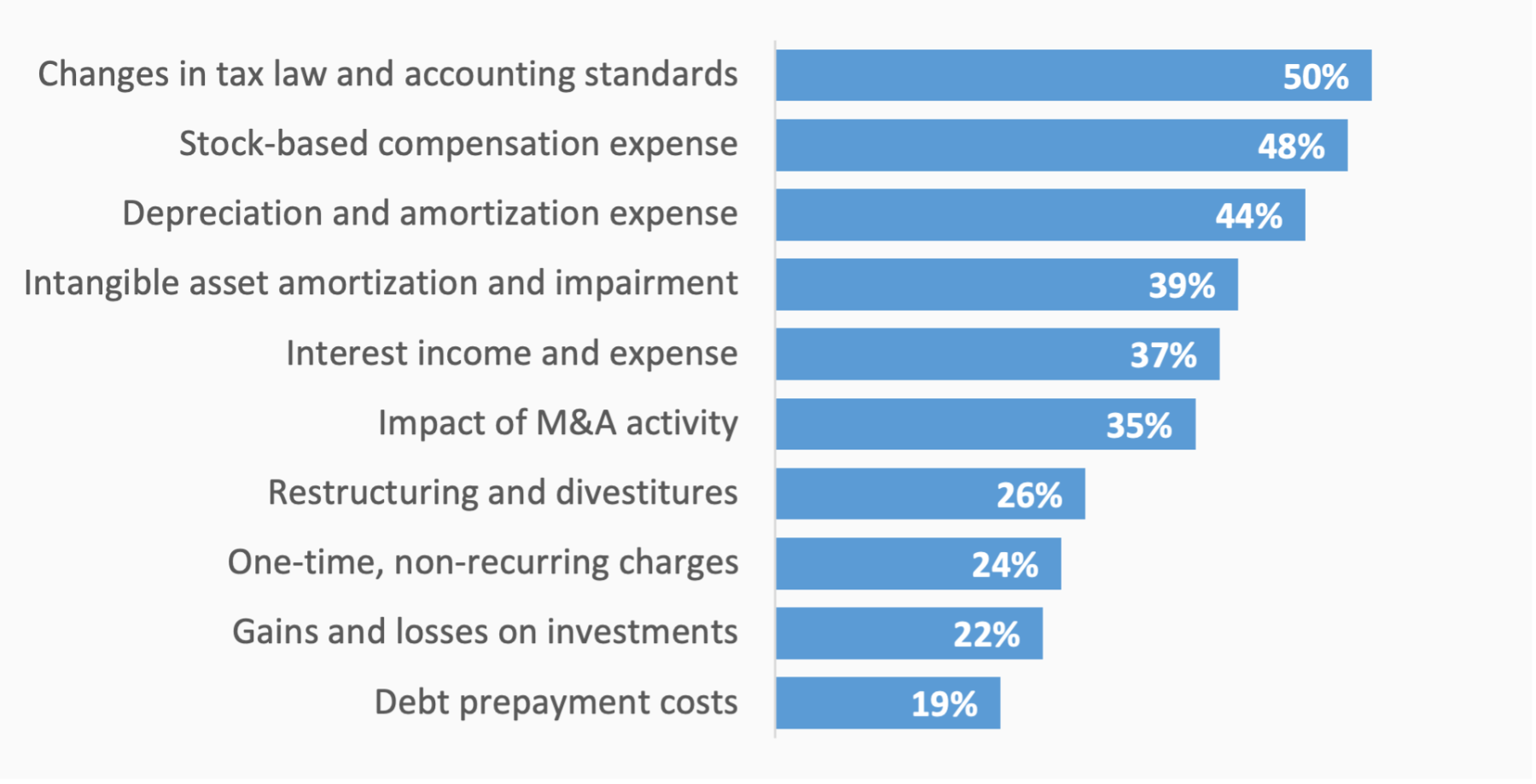

Our analysis reveals that the most common adjustments used in executive compensation include mergers and acquisitions, restructuring and divestitures, and changes in tax law and accounting standards (Figure 1).

Why don’t all companies use a non-GAAP metric that explicitly excludes the impact of events that fundamentally upend performance metrics (primarily tax law and accounting standard changes)? Most do—they just don’t call them non-GAAP metrics. Rather, they hardwire into the plan that the compensation committee will adjust as-reported results to exclude the impact of these events. It’s a subtle distinction (see the callout). But as long as the discretion afforded to the board is reasonable, it’s simpler to avoid a list of formal non-GAAP exclusions that’s too long.

More surprising is the prevalence of SBC expense and depreciation/amortization expense as excluded items. These relate to ordinary course activities, so are more likely to draw controversy. SBC is particularly controversial since its exclusion functionally allows executive compensation payouts to ignore how efficiently stock was used as a compensation tool.

Currency fluctuation exclusions have also been a topic of considerable debate. On the one hand, currency movements are exogenous macroeconomic factors that bear little on a company’s core operations. On the other hand, many argue that global companies should be expected to manage currency risk and that shareholders aren’t insulated from this risk.

**************

Compensation Committee Adjustments vs. Non-GAAP Performance Metrics

Non-GAAP performance metrics are actual metrics that begin with a GAAP metric and have a pre-specified set of exclusions that are performed to arrive at the corresponding non-GAAP metric. This is different from the compensation committee affording itself the ability to perform limited-scope adjustments when determining a payout amount.

Compensation committee latitude to adjust the calculated results is sometimes referred to as discretion. But normally the term discretion refers to the ability to subjectively alter payouts on a whim, which would taint the existence of an accounting grant date or trigger modification accounting. Here we’re talking about something much narrower: adjustments that must be performed to properly handle events impacting the as-reported results. These aren’t disclosed the same way as non-GAAP metrics. They’re buried in grant agreements, but not formally labeled as non-GAAP adjustments in the proxy.

In this regard, compensation committee adjustment leeway is valuable because it avoids a tidal wave of non-GAAP exclusions while providing a final check to ensure the payout makes sense. But if the allowable adjustments are too broad or subjective in their application, auditors will assert either that no accounting grant date exists or that an award modification has occurred. These are both deeply problematic outcomes, reinforcing why grant agreement language and framing matter.

Allowable compensation committee adjustments explain why we see a low prevalence of non-GAAP metrics that exclude the effect of tax law, accounting standard changes, M&A, and restructuring. Rather than formally specifying a non-GAAP adjustment that excludes the effect of these events, the compensation committee will simply apply adjustments to calculated results to immunize those results from the pre-specified factors.

**************

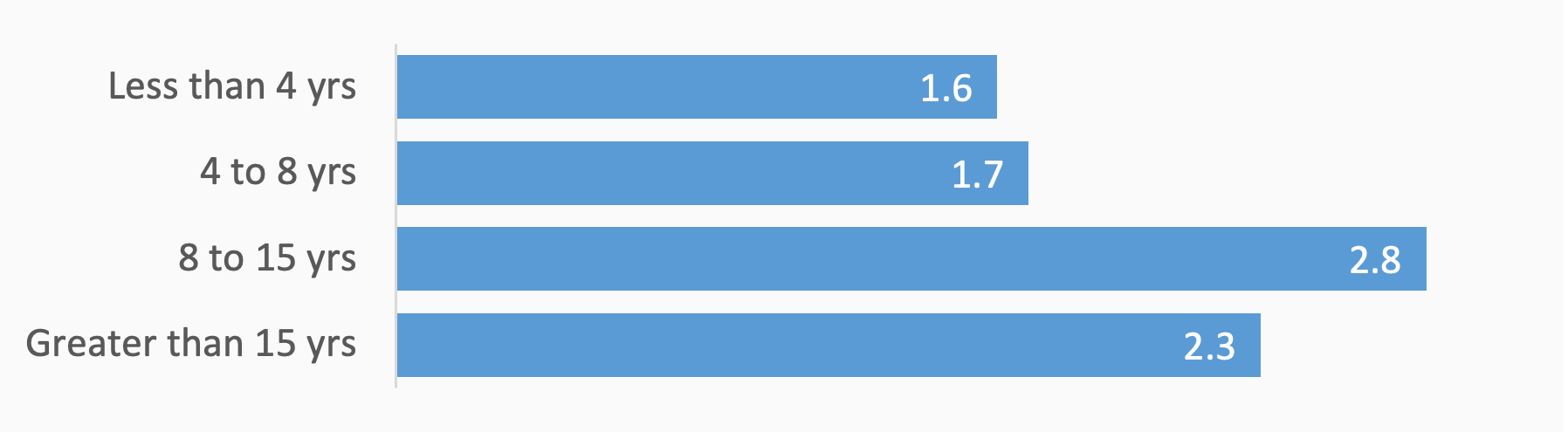

Next, in Figure 2, we look at the average number of exclusions by company maturity (years post-IPO):

You might be wondering why mature companies implement more exclusions in their selection of non-GAAP performance metrics. Mature companies face different challenges as they’re more likely to have complex global operations with frequent acquisitions, divestitures, currency management, and other related circumstances. In other words, their elevated complexity merits a broader scope of excludable items.

Remember that many exclusions are neutral in that they may help or hurt the payout—which is important in demonstrating the objectivity behind non-GAAP decisions. In this regard, SBC expense is an anomaly because it only serves to lower earnings. An important theme for boards is to apply non-GAAP exclusions (and permitted adjustments) consistently and on a principles basis so that their long-run effect is neutral.

Some exclusions only make sense to use for certain performance metrics. For example, many investors argue that that the impact of stock buyback decisions should be excluded from the EPS denominator whenever EPS is used as a performance metric in executive compensation awards. To our surprise, fewer than a quarter of companies that use an EPS metric in their executive compensation awards explicitly state that they exclude the impact of buybacks when measuring EPS.

While the SEC is unlikely to regulate how executive compensation is done (they’ll of course regulate how it’s disclosed), investors may exert pressure if they believe performance award payouts are being influenced by non-core activities. Anecdotally, we know that many companies that use EPS as a metric factor expected buybacks into their performance goal-setting process. They give the compensation committee discretion to adjust payouts that are driven by surges in buybacks (versus core performance).

Intracompany Exclusion Comparisons

In the prior section, we studied the role of non-GAAP earnings metrics in executive compensation performance award design. In the first installment of this series, we looked at common exclusions underlying non-GAAP street earnings, specifically the role of SBC expense. Here we combine those streams of thought to see if decisions are congruent—and what the arguments are for why they should or shouldn’t be.

Intuition would suggest that whichever items get excluded from a presentation of non-GAAP earnings to the Street should also be excluded from the measurement of executive compensation PSU payouts. When the same item is included or excluded in both non-GAAP street earnings and PSU measurement, there’s symmetry. When a metric is included (excluded) in non-GAAP street earnings but excluded (included) in PSU measurement, there’s asymmetry.

To study asymmetry, we segment our company data into four groups:

- Metric excluded from non-GAAP street earnings and excluded from PSU measurement

- Metric excluded from non-GAAP street earnings but included in PSU measurement

- Metric included in non-GAAP street earnings but excluded from PSU measurement

- Metric included in non-GAAP street earnings and included in PSU measurement

Then we look at the prevalence levels in groups two and three, calculating them as a fraction of groups one through three. We exclude group 4 from the denominator since our focus is on exclusion decisions that lack symmetry.

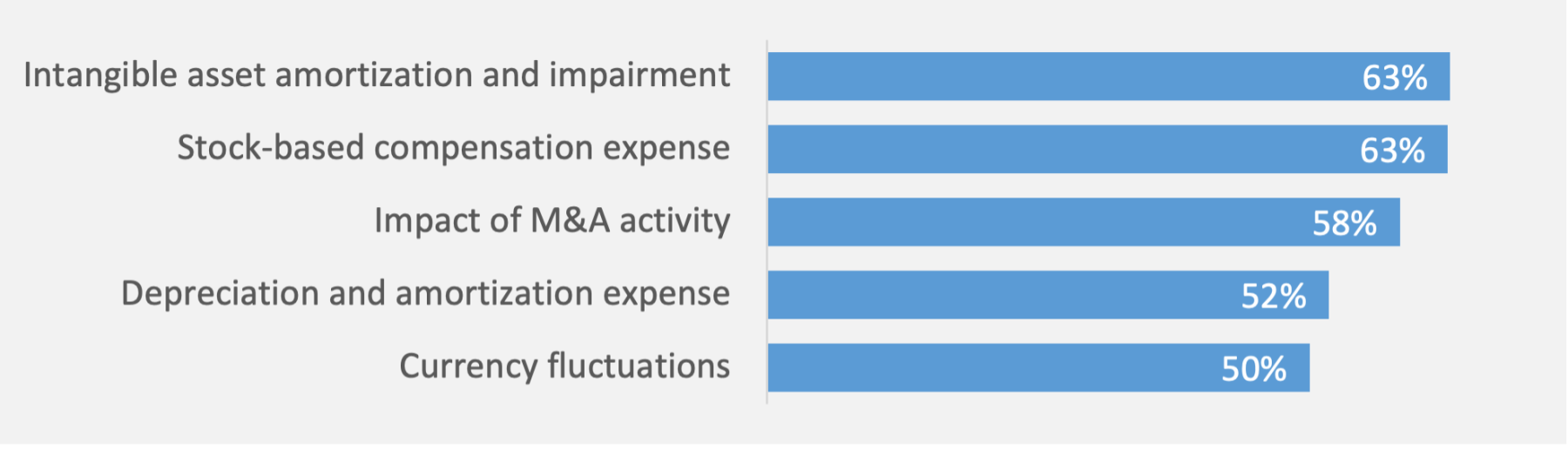

We’ll start with the metrics that are most likely to have symmetry, meaning they’re excluded in both domains. Here there’s alignment—management believes that investors don’t benefit from counting the metric and that executives’ performance award payouts shouldn’t be influenced by the metric.

Next let’s look at group two’s metrics, that is, where the metric is excluded from non-GAAP street earnings but included in PSU measurement. Figure 4 captures the metrics that have the highest prevalence of being excluded from non-GAAP street earnings but included in measurements of performance award outcomes. This means the company believes investors will benefit from those metrics being excluded from earnings but executives shouldn’t be shielded from those outcomes.

These cases seem reasonable. A key motive in designing non-GAAP street earnings is to help investors piece together their discounted cash flow models that look into the future. In contrast, PSU payouts are a reward for prior actions that are measured in the present. Still, you can see the prevalence levels hover around 50%, which suggests high divergence in practice.

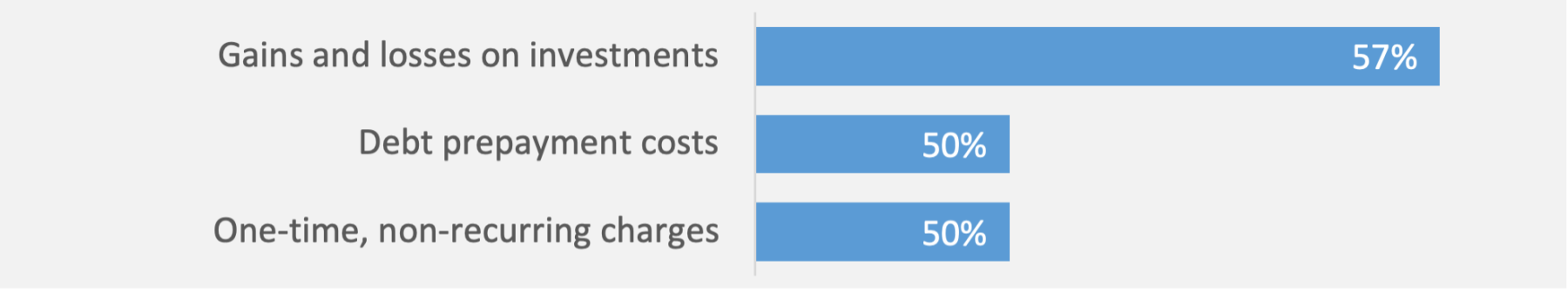

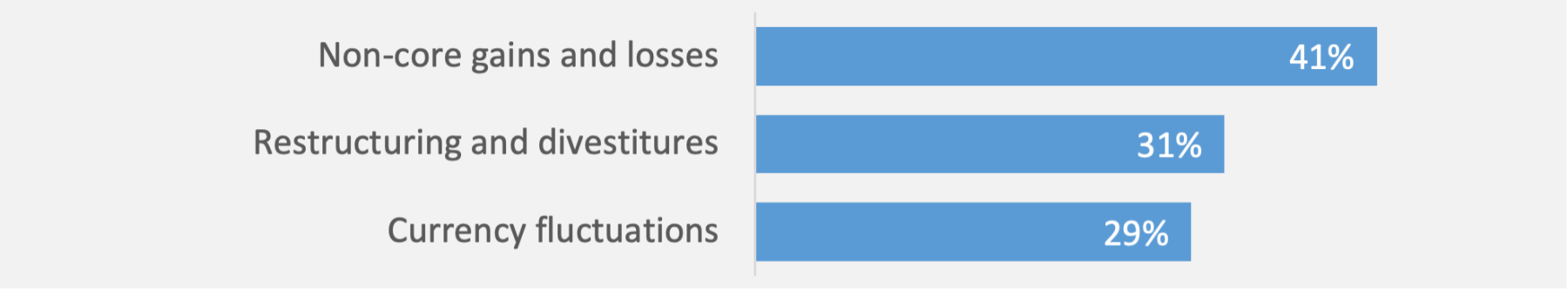

Figure 5 shows the inverse case where a metric is excluded from PSU certification but is included in presentations of non-GAAP street earnings.

These prevalence levels drop off quickly, suggesting a higher bar to include a metric in earnings presented to shareholders while excluding that same metric in executive compensation payout determinations. One potential explanation for the top metric, non-core gains and losses, is that these values are usually accretive to earnings (especially over the longstanding bull market) and therefore improve the earnings picture but would be problematic to base executive compensation payouts on.

As you can see, asymmetry isn’t necessarily a problem but it also merits consideration as to the rationale and whether that’s defensible. This is best done by bringing compensation and finance together to openly discuss the role of each non-GAAP exclusion and how/if it fits into each domain.

Recommendations and Strategies

Although most performance-based equity awards leverage non-GAAP metrics, the specific non-GAAP adjustments matter. Investors will press compensation committee members to prove that metrics are sufficiently rigorous and don’t create an asymmetry between executive pay and shareholder value creation.

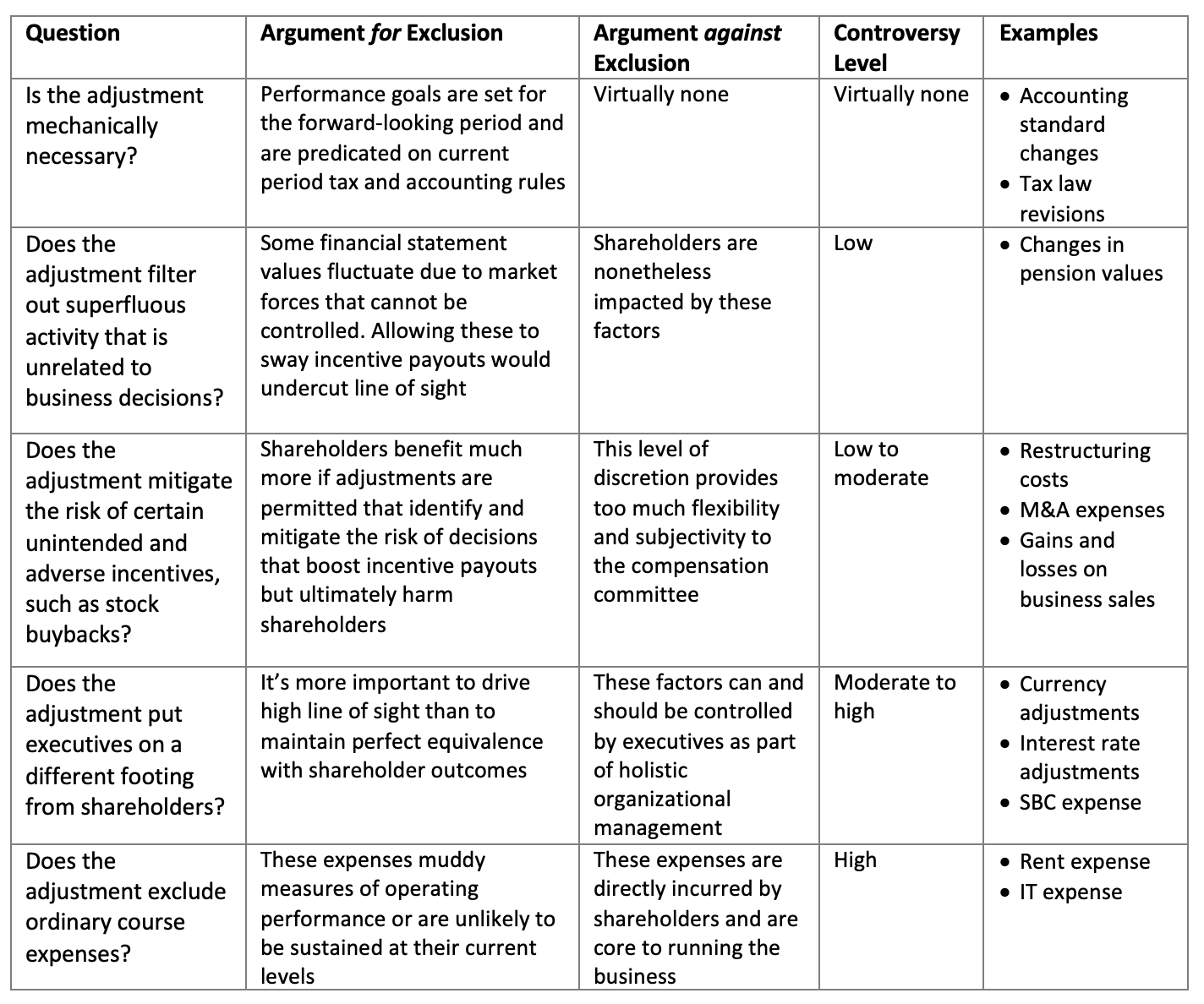

In assessing potential non-GAAP exclusions, it’s important to benchmark against your peers, maintain a strong narrative in support of your specific exclusions, and listen carefully to investor feedback. It also helps to have a decision-making framework with considerations like the following:

Exclusions need not be absolute. For example, some companies wish to filter out the effect of foreign exchange volatility, but don’t feel comfortable implementing a full-blown exclusion. Instead, they specify that adjustments will occur only for extreme outliers representing market volatility that management couldn’t control via hedging.

As noted earlier, it’s important to clarify that exclusions will be applied consistently on both the upside and downside. Shielding executives from harmful interest rate movements, while allowing them to benefit from favorable interest rate movements, would be highly controversial. This is what makes SBC expense such a controversial exclusion.

Plan for more scrutiny on the topic of performance goal-setting and metric specification. Proxy advisors have tried to make this a priority, but because the concepts are hard to fit in a simple framework, there’s still a general lack of prescriptive guidance. As institutional investors continue to strengthen their research arms, we expect to see more scrutiny in this area.

Wrap-Up

Non-GAAP metrics are a complex topic, in both the presentation of earnings to the Street and the structuring of executive compensation awards. Each has similar, but different, priorities and risks.

In this second installment of our series, we expanded on the first installment’s focus on SBC expense as a controversial non-GAAP metric by looking at how executive compensation awards are structured using non-GAAP metrics. Fundamentally, executive compensation is about driving business outcomes that are important to shareholders. This means establishing metrics that reflect shareholder value creation, deliver line of sight to factors executives can control, and avoid creating adverse incentives.

Sometimes this is done not in the specification of a non-GAAP metric but through compensation committee discretion to automatically adjust certain as-reported results. Some non-GAAP exclusions are more controversial than others. The Goldilocks solution is to eliminate earnings fluctuations that don’t reflect core operational performance without inserting a wedge between how executives are assessed and how shareholder returns accrue.

Finally, we looked at the circumstances in which it can make sense for the exclusions underlying non-GAAP street earnings to diverge from those used in executive compensation performance awards. While symmetry between measures is generally a good thing, we also found instances where specific divergences are appropriate. The driving factor is whether a specific exclusion is needed to avoid creating adverse operating decisions, such as holding on to a cash cow business unit because it generates in-period cash flows but no longer belongs in the corporate portfolio.

Non-GAAP metrics are powerful tools in communicating corporate performance to the Street and in structuring executive compensation awards. Please don’t hesitate to reach out if we can be helpful in evaluating any of the topics discussed here.

[1] In addition to periodic enforcement action, the SEC’s Compliance and Disclosure Interpretations guide much of how companies approach the disclosure of non-GAAP earnings metrics.

[2] SBC awards refers to long-term incentive awards, which generally vest over multiple years and link pay to one or more performance metrics. Short-term incentive awards are usually paid in cash and cover performance over a single fiscal year. These also may be based on non-GAAP metrics. In this paper, we focus our research on long-term incentive awards, but the concepts generally apply to short-term incentives as well.

Acknowledgements: We would like to thank our colleagues, May Polon, Ronuel Micu, and Kim Racacho, for all their efforts with compiling and preparing data used in this paper.