Dilution: What to Know Today about What Could Happen Tomorrow

Dilution is a complex matter for any investor. Many of our readers’ most impactful understanding of dilution may come from an iconic scene in the movie “The Social Network,” in which we learn that while other Facebook owners’ stakes were not diluted, co-founder Eduardo Saverin’s ownership was reduced to a paltry 0.03% of the company. While Facebook offers a cautionary tale, it’s far from the typical effect of dilution.

In this article, we’ll provide a brief overview of dilution followed by some illustrative examples of the impacts of dilution plus typical anti-dilutive provisions. We’ll dive into the question of how much equity to issue and the pros and cons of dilution as a tool. Finally, we’ll discuss dilution’s effect on valuation and what that can mean for your firm.

Economic Rights, Control Rights, and Dilution

First, let’s understand the difference between economic rights and control rights.

The SEC defines dilution as a situation where “a company issues new shares of stock, leaving the existing stockholders with a smaller percentage ownership interest in the company.” This could happen immediately in the case of new shares issued during a fundraising round. It could also happen over time if securities such as employee stock options are exercised, or preferred shares and convertible debt are converted into common stock.

Take the following hypothetical example:

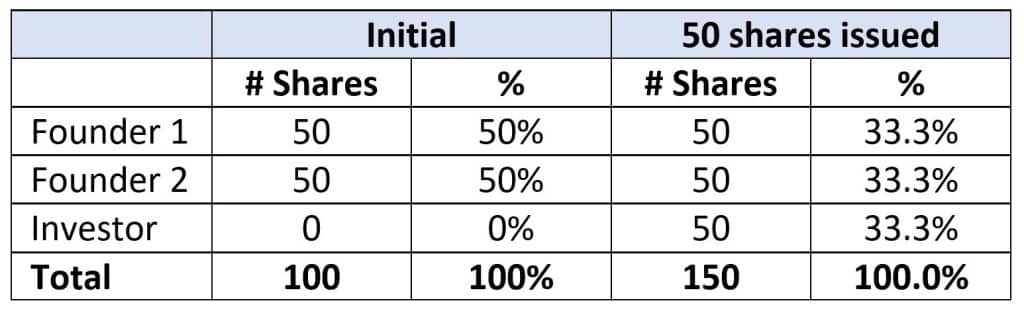

Two founders each own 50 shares, representing 50% of Company A and total control between them. Now they sell an additional 50 shares to an outside investor.

After issuing the new shares, their ownership stake declines from 100% of the company to 66%. They still hold a controlling position, but it’s not as strong as before (Table 1).

Table 1: Dilution of Each Founder’s Ownership from 50% to 33.3%

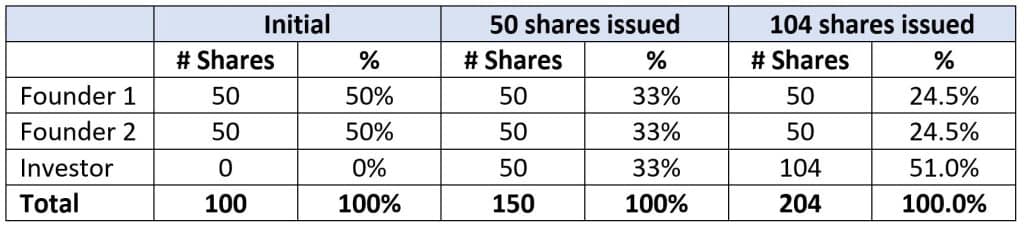

If enough shares are issued, dilution can become so great that control now passes from the original founders to the outside investor. This may be intentional if the founders sell the shares directly, but it could also be unintentional, e.g., if the new shares were part of a conditional exercise of convertible debt (Table 2).

Table 2: Dilution of Each Founder’s Ownership from 50% to 24.5%

In this example, we consider all shares as equal in ownership and control. In reality, it’s also possible to have shares with different amounts of control—for example, a founder may hold shares with high numbers of votes.

Dilution of ownership and control isn’t necessarily a bad thing. It’s just a lever to manage. Owning 1% of a $2 million company is no more or less valuable than owning 2% of a $1 million company. Further, the reason investors become diluted isn’t necessarily because the CEO decided to grant shares to some of his friends. The company has a fiduciary duty not to give out anything without getting reasonable value in return. So dilution may occur if, for example:

- A new investor buys equity in the company

- A company issues new stock and uses it to purchase another firm

- A debtholder in a struggling company converts some or all of their debt stake into equity and allows the company to avoid coupon payments

- A company issues warrants as a sweetener alongside a debt or equity issuance

- A company issues warrants to a key vendor in lieu of cash in order to form a strategic relationship

However, understanding the dilutive impact of a company’s actions—not to mention the potential cost of any anti-dilutive steps—is a key part of understanding a company’s structure and governance.

Anti-Dilutive Provisions

Equity-linked instruments include employee stock options, warrants, convertible debt, and other securities allowing for the purchase of equity. They typically include certain features to prevent the holder from having their ownership interest diluted due to various corporate actions. The most common anti-dilution provision, present in almost every security, provides for an equitable adjustment upon a stock split. For example, if IBM split its $100 shares into two $50 shares, the warrant would adjust to cover twice as many shares at half the price. That means you could buy two new post-split shares at $50 each—the economic equivalent.

More complex instruments may include additional features to preserve their control rights. Some that we’ve seen are:

- Rights to participate in future offerings at market price to maintain a level of ownership

- Convertible bridge notes that allow for the purchase of a variable number of shares based on a future financing round price

- “Super control” shares that guarantee the holder a fixed voting percentage without economic rights

- Warrants that adjust the strike price and number of shares if there’s a down round, i.e., a subsequent offering at a lower price[1]

- Securities that convert into a fixed percentage of the company as of a future date, or alternatively where the shares are set as of an event such as an IPO or other public listing

In each of these cases, ownership is flexible. Events that can happen in the future may mean investors lose some of their ownership, and potentially value, as a consequence of having given these rights in the past.

You may have noticed the above list is generally sorted from the lowest level of protection to the highest. Indeed, a good way to think about this is how much the holder can increase their ownership while paying a below-market price.

The Upside—Give and Take

It’s easy to look at dilution as strictly negative. But doing so ignores a real-world feature: A share of equity is an enticement, and you get value for giving it out. A few examples bear this out:

- An employee may take stock options or restricted stock instead of cash payments. While this dilutes the other shareholders, it helps to align them with other investors and replaces cash outlays for the company

- An investor will pay a higher price for securities with anti-dilutive features, thus resulting in more cash

- Convertible securities typically dilute only if the value of the company goes up. Dilution is easier to take if everyone is doing well. Meanwhile, the company pays less interest in all situations

When considering future dilution, consider not just the costs of the dilution but the benefits as well.

Deciding How Much to Issue

So how do owners decide how much equity they’re willing to give up? To answer this question, investors should look not only at the amount of control they’re ceding, but the potential returns on the deal itself.

A simple example illustrates this. Suppose n is the fraction of the company you’re looking to give up. The deal is a good one if it makes the company worth more than 1/(1-n). To use a numerical example, if a venture firm offers to fund you in return for 7% of your company, then 1/(1-0.07) is 1.075. In that case, you should take the deal if you believe the deal will improve the value of the firm by more than 7.5%.

If the company is worth $1 million and you gave up 7%, but the deal increased the value of the firm by 10%, your 93% share would now be worth 0.93 x 1.1 x $1 million or $1.023 million. Effectively, the dilutive action of issuing shares creates a hurdle rate for new investment (effectively a goal to strive for).

The Poison Pill—Dilution as a Tool

While the anti-dilutive tools above are designed to protect existing shareholders, shareholder rights plans take this one level further in the form of so-called poison pills. These can be an effective defensive tactic against an aggressive takeover from a hostile investor. Typically, existing investors are given the chance to purchase company stock at drastically reduced prices, thus diluting the stake of the hostile investor and staving off the bid. Two recent high-profile cases show how this has operated in order to allow existing shareholders to manage the threat.

In 2018, ousted Papa John’s Pizza founder John Schnatter, who owned 30% of the company stock, threatened a takeover of the firm. The board adopted a poison pill provision that permitted the company to sell its stock to shareholders at half its market price if Schnatter increased his stake to 31%, or if anyone else amassed a 15% stake without prior board approval. The plan expired after a year to allow the board time to consider possible buyout offers.

Netflix saw a similar situation in 2012 when activist investor Carl Icahn took a 10% equity stake in the company as a means of gaining board influence. In response, Netflix’s board adopted a poison pill that diluted the stake of anyone holding more than 10% of the equity by offering other shareholders the right to purchase two shares for the price of one.

Similar to a more traditional takeover defense is one designed to prevent a legal change in control and protect a company’s net operating loss carryforwards under Section 382 of the Internal Revenue Code. We aren’t taking a position on the advantages and disadvantages of such a plan, but want to be clear on this use of dilution.

Going back to Eduardo at Facebook, the owners used dilution of ownership via another legal entity, simply issuing shares to other investors and leaving him out in the cold. At the time, they were able to use their voting power to dilute Eduardo’s share to virtually zero. But there are laws against simply diluting out owners and the resulting settlement from his lawsuit against the firm is reported to have been $4 to $5 billion. Not a bad return for an initial $19,000 investment!

Stock Buybacks—Reducing Dilution

We frequently hear about companies using stock buybacks to show they believe their shares are underpriced, as an alternative to issuing a dividend or putting cash on hand into the business. Indeed, share buybacks are the exact opposite of dilutive issuances. Instead of selling shares for money, the company pays cash in order to buy back shares and reduce the number of shares in the market, increasing the remaining shareholder’s ownership stake.

Of course, there’s no free lunch with stock buybacks. Buying shares at a market price is a neutral transaction, and while remaining owners have a higher stake, the stake is of a company that’s now less valuable.

An example is best to understand.

- Company X has 1 million shares outstanding, priced at $10 each.

- It has $1,00,000 in cash.

- Management decides to buy 100,000 shares at $10 each.

After the buyback, the company will have 900,000 shares of stock, still at the $10 price. So the holders own 10% more of a company that’s worth 10% less.[2]

Dilution, Ownership, and Share Counts

It’s important for company owners to get a hold on what the actual share structure is. We typically see three share counts come from companies:

- Issued and outstanding. This refers to the shares that exist in the company today. The lowest of share counts, it incorporates none of the dilutive impact of outstanding securities

- Fully diluted. The fully diluted share count is the maximum shares outstanding based on the current capital structure. This count assumes all conversion and exercise features of any outstanding instruments are used to determine the overall potential share count. If a firm grants options for 1,000 shares, those shares would count as issued only if they’re exercised (instead, they’re reserved for future issuance). That’s the case whether they convert at half or 10 times the stock price. They would, however, count toward the computation of fully diluted shares

- Authorized. The authorized count goes beyond the fully diluted share count as it includes any shares that the company has the rights to issue, but has not yet issued. For example, the remaining share pool for stock options are authorized, but because they haven’t been issued, they aren’t part of the other counts

When we consider dilution, we use frameworks that are more nuanced. As an example, if the stock price falls, options won’t be exercised and stockholders will own a larger stake of the (lower-valued) company. Therefore, we look at dilution based on what we expect to happen at each company value or stock price in the future. This variable dilution model is most relevant to determining the actual stake and value.

Dilution and Valuation

ASC 718 offers a good way to think about dilution. The guidance in ASC 718 10-55-49 notes that while both public and private entities should consider the impact of dilution from awards of share options, public companies may find very few cases where dilutive adjustments are needed.

If the market for an entity’s shares is reasonably efficient, the effect of potential dilution from the exercise of employee share options will be reflected in the market price of the underlying shares, and no adjustment for potential dilution usually is needed in estimating the fair value of the employee share options. For a public entity, an exception might be a large grant of options that the market is not expecting, and also does not believe will result in commensurate benefit to the entity. For a nonpublic entity, on the other hand, potential dilution may not be fully reflected in the share price if sufficient information about the frequency and size of the entity’s grants of equity share options is not available for third parties who may exchange the entity’s shares to anticipate the dilutive effect.

In fact, during our valuations, we may take a few approaches depending on the situation.

For public companies, we almost always consider that all dilution is in the stock price already. The only exception is if dilution is somehow unknown to the market (perhaps due to a future offering). In this case, however, we believe that the dilution would only reduce the stock price if the company didn’t receive similar value in return, a very rare situation.

For private companies, we assume that any investment would acknowledge the existing dilution. If we’re allocating the value among securities, we use a model that takes the dilutive impact of all share classes throughout the capital structure into account.

Final Thoughts

People fear what they don’t understand, and dilution is certainly one of those areas for many. We note that dilution can create winners and losers. Mostly, though, it’s an essential tool for creating larger businesses and opportunities, as well as aligning shareholder and company interests. With that said, like all financial tools, it should be fully considered and understood as part of any transaction.

[1] If this is ringing a bell, you may have had to deal with these in the past as they caused liability treatment for any instrument that had them. For a more thorough review, see our prior analysis here and our cheering for the end of the mark-to-market era here.

[2] Some readers may be concerned that dilution can be bad for share price and buybacks can be good. In fact, many companies and investors believe that a buyback signals to the market that they believe their stock is underpriced, prompting stocks to react immediately. With that said, finance literature is at best mixed about the long-term value effects of buybacks, and we stick with our assumption that the market is efficient and buying things at market price cannot generate value. On the other hand, metrics such as earnings per share (EPS) are directly impacted if the company changes the number of outstanding shares, and much has been said about executives leveraging buybacks to hit EPS targets.