10 Themes Shaping the Decision to Restore Underwater Equity Incentives

The economic fallout of COVID-19 has made its way to equity and executive compensation.

At many companies, long-term incentive (LTI) awards—particularly those based on multi-year, absolute financial metrics—are in trouble due to changing demand and costs in the wake of the pandemic. Annual bonus plans are similarly at risk, though these have more levers and it’s easier to apply discretion to payout outcomes.

We’ve had hundreds of conversations with clients, auditors, lawyers, and accounting standard-setters this year about strategies for restoring underwater equity incentives. We’ve looked at these issues in view of their incentive, retention, proxy, shareholder, and financial accounting implications. And this summer, we organized these perspectives into a comprehensive FAQ on equity modifications and discretions. Here’s a summary of 10 key themes from that FAQ, all of which should be on your radar as we head into the new year.

1. Exercising discretion to adjust payout outcomes could be favorable

Most equity plans give the compensation committee some ability to exercise discretion and adjust the performance results. The textbook examples are adjusting performance in light of an accounting standard change or in response to M&A and divestitures.

Many companies have been exploring whether they can exercise COVID-19 discretion over equity award payouts. If possible, this would bypass the ASC 718 modification accounting framework, meaning the cost impact of the action would be discussed in the narrative of the proxy but not the proxy tables.

The fear with adjusting equity payouts isn’t so much the hit to the 10-K, it’s the double-counting that occurs in the proxy summary compensation table (SCT). As we’ll explain shortly, avoiding modification classification is usually a stretch. For most companies, the best strategy will be to put together a modification that minimizes incremental accounting cost by thoughtfully pulling the right award levers.

2. Discretion applied to long-term equity awards is often a dead end

The word “modification” appears 288 times in ASC 718 whereas the term “discretion” appears only twice, with neither instance pertaining to this concept. That’s another way of saying that there is no direct framework in ASC 718 related to the compensation committee adjusting payouts ex post using their legally afforded discretion.

Rather, we’re given a framework for specifying an accounting grant date (which is usually upfront at issuance) and a principle that changes to the deal struck at the formation of the grant is a modification to the terms. The grant date solidifies the value of the award, and any term or event that prevents upfront specification of a grant date results in variable accounting until a grant date can be established.

The core tenet of establishing an accounting grant date is that a mutual understanding exists between the company and the recipient about all key award terms. One way to test this is to see whether there’s excess subjectivity in how the award will be paid out. By way of example, if the compensation committee can say they were impressed by the CEO’s leadership and wish to adjust her payout upward by 20%, this implies one of two things:

- The award terms were not locked down upfront and afforded this degree of subjectivity

- The award terms were locked down and now the compensation committee is choosing to modify them

This Catch-22 will create risk during your external audit process. Your auditor may focus on alternative A, arguing that if you really had so much discretion to subjectively adjust the performance outcome, then there couldn’t have been an upfront accounting grant date. Or they might follow alternative B and concede that, at the time of grant, the key terms were locked down such that any action now is a carte blanche change to those terms.

Alternative A is by far the bigger risk of the two. If there isn’t an accounting grant date, then there is a soft and hard application of that conclusion. The soft application is that, going forward, any new awards using the same plan language cannot have an upfront grant date. The hard application is that the awards being adjusted were erroneously assigned an upfront grant date, so an error correction (or potential restatement) is in order. Although the latter approach seems untenable, even the softer outcome is deeply problematic because it taints the accounting grant date on any future award relying on similar plan language—even if there is never an intent to exercise far-reaching discretion again.

3. Shall language can indicate a reasonable basis for exercising discretion

In a limited number of contexts, discretion can work. This begins with careful review of the language in the award agreement. The more specific and deterministic the language governing when and how an adjustment can be made that relates to a pandemic or “natural disaster,” the stronger the argument that an adjustment linked to COVID-19 is not an in-substance modification.

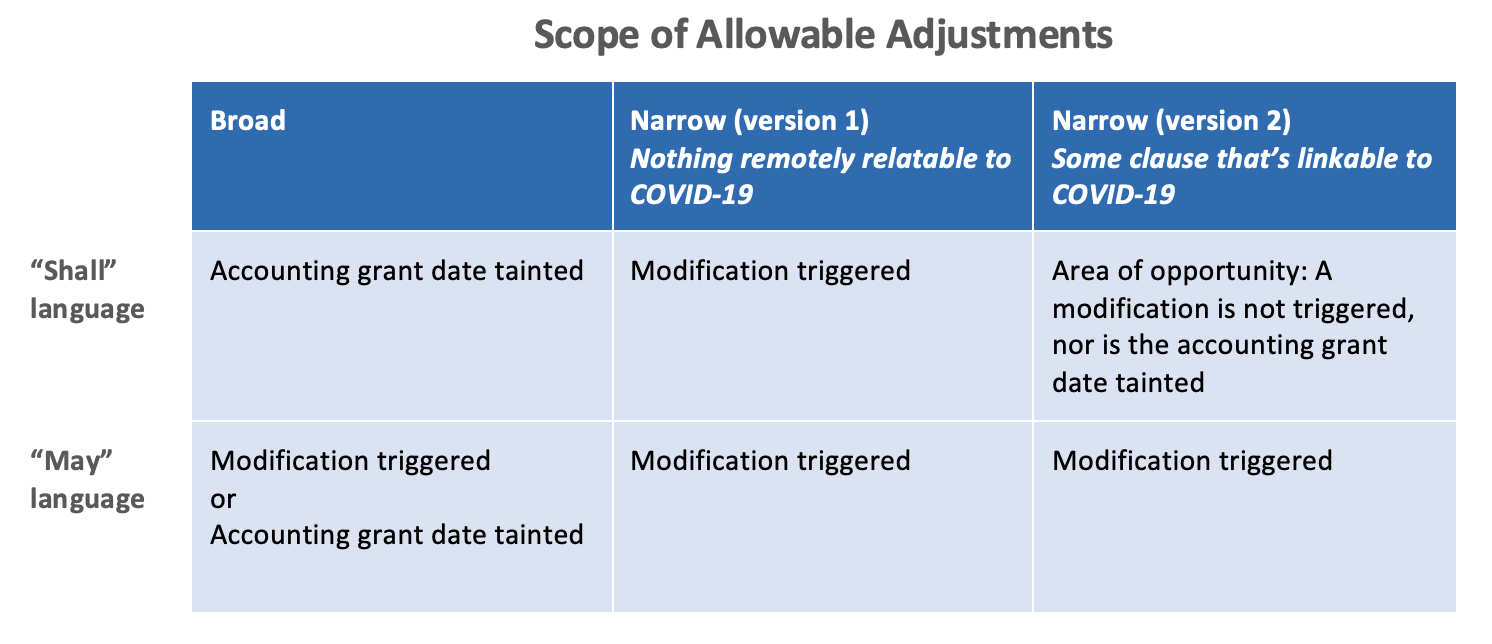

Below is an extract of the framework we use to evaluate adjustments and the likelihood of negative repercussions.

In short, we draw a distinction between “shall” and “may” language, the former of course obligating the committee to a certain type of action and being a prerequisite to discretion not being reclassified into a standard modification. If the compensation committee may take action and so chooses to, it all but guarantees modification treatment. Similarly, the language explaining allowable adjustments must be linked specifically to a pandemic, otherwise we encounter the same problem where the committee is exercising choice and that choice triggers modification classification.

4. Most payout adjustments will be classified as modifications

Unlike the virtually nonexistent discussion of compensation committee discretion, ASC 718 provides a clear and comprehensive framework surrounding modification triggers and treatments. ASU 2017-09 clarifies and expands that framework further. Quite simply, any change to the terms of an award that alters its fair value, vesting conditions, or balance sheet classification will trigger an accounting modification.

One way to think of this is that any revision to the economics of the original deal struck at the grant date is a modification. Regulators and standard-setters tell us it’s not an accident that ASC 718 has nothing to say about compensation committee discretion. Why? The governing principle is a point-in-time determination of the grant date such that any subsequent change to that deal has only one treatment, which is the rather robust modification framework in the guidance.

As a quick aside, how does that conclusion jibe with the fact that compensation committee discretion has historically been used across numerous contexts—from adjusting for M&A to tax law and accounting changes? Our view is that even these adjustments have made standard-setters a bit queasy. Still, they have accepted them due to the use of “shall” language and a clear adjustment methodology written into award agreements. Many financial services companies found this out when their auditors concluded discretion language on excessive risk-taking precluded an upfront grant date. In short, there isn’t a bright line but there is a line, and most experts will tend to find COVID-driven adjustments to be well past that line.

Back to modifications: There are four types, each with different accounting implications. They’re determined based on the status of the vesting probability pre and post-modification. The two most common modifications—especially during the pandemic—are Type I (probable to probable) and Type III (improbable to probable).

The accounting for modifications boils down to a fair value measurement of incremental value created by the action. Mechanically, the value of the original award right before it’s modified is compared to the value right after modification, and the differential is the incremental value of the original award. This gets added to the original fair value currently being amortized. Naturally there are some corner cases and a wealth of valuation technicalities to know, but these are the basics.

Let’s start with a Type III modification, which represents an effort to restore value to an award that’s on track to deliver nothing (thus the phrasing improbable to probable). With the pre-modified version of the award tracking at a zero-dollar payout, the incremental cost is simply the value of the award right after it’s modified—since the value immediately before modification, by definition, was zero.

A common situation in 2020 has been that awards are on track to pay out at some multiple, but one far below expectations, thereby prompting a desire to restore some of the lost value. For instance, an award may be tracking at a 20% payout and the compensation committee believes an 80% payout is more appropriate given the milestones achieved. This has both Type I and Type III qualities. That is, 20% of the award payout is unaffected by the modification, making this a probable-to-probable adjustment. However, 60% of the award is being modified from improbable to probable status.

An example of a pure Type I modification is an option exercise term extension. These relatively common actions usually take place in the context of a large termination event in order to give affected employees more time to exercise their vested options. Since vesting is probable both before and after the modification, this is a Type I modification. However, it can still create considerable incremental cost depending on how the valuation is determined. Importantly, that incremental cost is added to the original grant-date fair value being recognized and there is no mechanism for reversing any existing expense.

5. Modifications can have a misleading effect on the proxy

Regulation S-K requires modifications to be disclosed in the proxy if they give rise to incremental accounting cost. Essentially, modifications show up as new grants in the proxy tables, thereby giving the impression of double compensation since there is no vehicle for undoing the original award hitting the same proxy tables. Be mindful of the optics: A modification usually occurs during a down year, yet in the proxy it suggests a greater quantum of compensation.

Disclosure of incremental cost from a modification is required in both the SCT and Grants of Plan Based Awards Table (GOPBAT), and should be disclosed as compensation in the year of modification. Even if the modification has no incremental cost, it could still arguably be a “material modification” under the proxy rules, thus requiring narrative disclosure. Material modifications also trigger 8-K disclosure.

While a “less is more” strategy has often guided proxy disclosure, the prevailing best practice is to slow down and take the time to explain the compensation committee’s rationale for the adjustments. The double counting phenomenon especially bears discussion since the appearance of inflated compensation is an artifact of the proxy rules not containing a mechanism for adjusting expected or realizable values (which even the accounting rules in ASC 718 permit on certain types of performance-based awards).

Institutional investors and proxy advisors like ISS have expressed concern about modifications that offer executives something that shareholders do not get: a do-over. We discuss these messaging considerations and how to navigate incentive, retention, shareholder, and proxy advisor constraints in the November/December issue of The Corporate Governance Advisor.

When pressed for a number—that is, what post-modification payout is reasonably safe from an investor perspective—the details obviously differ from case to case. But our experience is that payouts between 50% and 75% are unlikely to trigger material ire. As payouts head up (and above) target, the risk increases markedly.

6. Performance metrics can be revised downward, but it’s a blunt instrument

One way to restore broken incentives is to revise performance goals downward. The rationale is simple: When performance goals on outstanding LTIPs were being set, there was never even a remote consideration that a once-in-a-century pandemic could occur and bring such disruption. (Of course, the counterargument is that the whole point of equity compensation is to share both the gain and the pain, just as shareholders do.)

If the goals are no longer applicable or achievable, the reasonable solution is to revise them, and there are various ways of doing so. We’ve seen companies simply adjust the payout to target, regardless of where the award is currently tracking at under the original terms. We’ve also seen them add a floor payout to the current award or lower the performance target.

What all these modifications have in common is that they allow higher payout of the award. The portion of the payout that’s improbable before the modification, but probable after, is subject to Type III modification. In other words, it essentially triggers a new grant.

Some companies have adopted this blunt instrument approach, but in a way that’s creative and insightful. The key is understanding that downward revisions can look like a money grab when done arbitrarily. One alternative is to calculate what the award would have paid out at (for example) two or two-and-a-half years of performance, then anchor to that number. Or, if the award has multiple metrics, determine the payout as if the metric weightings were changed. In short, the objective is to convey in the proxy that the resulting payout is reasonable and supported by evidence, instead of a subjective desire on the part of management or the board.

7. Performance metrics can also be replaced with more appropriate ones

A second approach—one we’ve seen work well—is to replace the original performance metrics with new ones and argue that the new ones are not only more appropriate, but also rigorous. Of course, this will trigger a modification, but the messaging is arguably better than simply lowering targets.

The most common case we’ve seen is converting absolute financial metrics to a relative TSR metric, on the basis that absolute financial goals make no sense during periods of upheaval. The appeal of relative TSR metrics is that they can’t be gamed. They can also be structured with attractive governance features like steep targets and absolute TSR payout caps.

The determination of incremental cost depends on the point-in-time payout expected at modification and the valuation of the new award and its metrics. The higher the payout expected on the original award at the time of modification, the lower the incremental cost. When structuring the design, it’s worth modeling multiple scenarios on the new metric(s) in an effort to minimize the value and therefore reduce the overall incremental cost calculation.

8. New performance metrics can be added alongside existing ones

Adding a new metric to an outstanding award is a similarly compelling option.

Although the concept is not dissimilar to a metric substitution, the accounting and overall optics are different. The simplest approach is to add a “kicker” to the existing award that provides an additional avenue for payout. Usually, this will be a relative TSR kicker, but any metric is on the table. The accounting is simple: The value of the new metric(s) at the time of addition constitutes the incremental accounting cost.

9. Changes in employment status can trigger modifications as well

Widespread terminations or furloughs can also trigger modifications. Earlier, we discussed the standard post-termination exercise window extension for stock options that terminated employees hold. Executives may receive more specialized treatment, especially when performance-based awards are involved. Watch out for the details of exit arrangements, especially if you hear about them prior to their formalization.

Furloughs are different. Since furloughed employees aren’t terminated and their awards aren’t forfeited, the real question is how to treat expense during the duration of their furlough. The answer depends on whether the vesting date is extended to not count the furlough period or whether vesting continues throughout the furlough period.

This is the same question that we face with a standard leave of absence. If the vesting is extended, then expense recognition is paused and only resumed once employees return and begin rendering services again. However, if vesting continues during the furlough period, then most argue that expense should continue to be recognized without any revision to the pattern of accruals.

Demotion is a third category. The question we often hear is what treatment applies if shares are taken away from a recipient due to demotion. ASC 718 has nothing to say about this, and it’s not particularly common in practice.

The simple treatment is to classify the event as a cancellation without consideration, in which ASC 718 specifies that all remaining expense should be accelerated. However, if you can demonstrate that the reduction in responsibilities is significant and the original award is no longer commensurate with the new position, then an argument can be made to treat the cancellation as a forfeiture and therefore reverse expense.

10. Be careful about managing the share pool

The final theme is share pool management. With the general recovery in the capital markets, this is primarily an issue for companies in highly disrupted industries where stock prices have not recovered.

With a marked decline in the stock price, burn rates intensify. It’s possible to burn through your share pool one or more years quicker than originally modeled. The simplest solution is to ask shareholders for more shares. However, due to time or other constraints, this isn’t always possible. An alternative is to change the settlement method from shares to cash, which triggers an equity to liability modification. At the time of modification, the award becomes a liability and must be marked to market every period thereafter, provided the cumulative fair value recognized can never fall below the original grant-date fair value.

A decision with ripple effects

Adjusting long-term incentive award payouts is challenging and complex. Without a doubt, the simplest solution would be to do nothing and simply adjust the following year’s grant, or maybe sweeten payouts in the annual bonus plan. But many companies have concluded that the risk of doing nothing exceeds the benefit.

We wrote our modifications and discretion FAQ as a comprehensive guide to addressing long-term incentive restoration objectives. The central challenge is balancing the retention and motivation needs of executives with other company interests. These include the proxy disclosure obligations and corresponding optics to shareholders and proxy advisors, as well as the financial accounting underpinning that disclosure.

If you’d like to discuss any of these topics, we’d be happy to serve as a resource.