Clawbacks: Updates From the Field

The SEC’s Dodd-Frank clawback rule went live last year. That means board-approved clawback policies needed to be in place by December 1, 2023, and incentive-based compensation received after October 2, 2023, is subject to the policy.

As we’ve discussed in prior blogs and webcasts, Dodd-Frank clawbacks are radically more restrictive given their no-fault and no-discretion nature. As of March 2024, we’ve worked on two live Dodd-Frank clawback cases and discussed restatements and price impacts with many more companies conducting readiness projects.

While our involvement has been broad, our principal area of focus is determining erroneously awarded compensation related to total shareholder return (TSR) and stock price metrics (“market metrics”). This will likely be one of the most challenging dimensions of a recovery analysis since it requires building a model that estimates what the stock price would have been had the financials never been misstated (the adjusted or “but-for” stock price).

In this article, we discuss 15 practical issues for dealing with market metrics that every board member, general counsel, CFO, and CHRO should be apprised of in the unfortunate and unlikely event a restatement occurs. The issues are organized into four sections:

The basics on the rule, standard of care, and process—in other words, getting started on the right foot

Event Studies (Top-Down Methods)

An introduction to the methodology cited by the SEC, an event study approach, which is a top-down methodology for linking the restatement to the stock price

Fundamental Analysis (Bottom-Up Methods)

A look at a “bottom-up” approach that uses fundamentals-based analysis to forecast the but-for stock price

Best Practices and Success Factors

Some tips for an effective analysis, based on our experience so far

Getting Started

1. Get key parties aligned on the central issues when conducting a recovery analysis that encapsulates a market metric.

The SEC rule release is new, complex (230 pages), and deeply technical. Although it wasn’t a surprise that the SEC required market metrics to fall within the scope, these introduce considerably more complexity than basic financial metrics where the clawback amount can be determined using basic math. You’ll need time to get the board, executives, and project team members up to speed on what they need to know, so start doing this ahead of a restatement.

The recovery analysis is about isolating how the incorrect financial results may have inflated the stock price. However, if the stock price also suffered for tangential reasons, such as negative governance signaling, these are confounding factors that shouldn’t be included. Clarifying what the study is and isn’t supposed to measure is an essential starting point.

It’ll also take a few conversations to align on the appropriate techniques for measuring the adjusted stock price and why this is required under the SEC’s rule. (Later on, we’ll walk through the differences between top-down and bottom-up methodologies and their respective merits.) These are foundational details to put on the table early on.

The goal is to determine the compensation that would have been earned had the correct numbers been reported all along, therefore providing a parallel-universe stock price trajectory. This is why the output is called the adjusted or but-for stock price.

To help get everyone on the same page, we’ve collaborated with clients on a playbook that sketches out the relevant activities, owners, and order of operations. This is not dissimilar to the concept of running tabletop exercises in preparing for a potential cyber breach.

2. Design the recovery analysis with a clear understanding of the standard of care (a “reasonable estimate”).

When measuring erroneously awarded compensation (if any) in the context of market metrics, start with the standard of care.

The bar set forth by the SEC is to develop a “reasonable” estimate of the impact of the restatement on the market metric (page 63 of the final SEC rule). There’s not a single, unequivocal way to do that. At the same time, the documentation and work product underlying the estimate must be maintained and provided to the listing exchange, which is to say this is very much a formal exercise and not a rough estimate.

The SEC notes in the final rule that issuers may use “any reasonable estimate of the effect of the restatement on stock price and TSR.” There are a handful of approaches we believe are reasonable, though it’s possible for a generically reasonable technique to be inappropriate in certain fact patterns. We’re also aware of techniques that are patently unreasonable, largely because they don’t conform to commonly accepted principles in financial economics.

The purpose of the analysis is not to develop the most complex or elaborate calculation methodology. Nor is it to drive toward the lowest number. Bear in mind that many plaintiff litigators will be looking for indications that the recovery analysis was gamed to shield officers. The specialist’s job is to consider the fact pattern, assess generally reasonable techniques in light of that fact pattern, and select a methodology that produces a reasonable estimate.

With that said, a reasonable method should focus only on the impact of the restated financials. This impact may be substantially smaller than damages analyses on related shareholder lawsuits that are focused on the broader impact of the restatement (e.g., mismanagement, poor controls, etc.). The point of the Dodd-Frank clawback is not to punish officers for having a restatement, but rather to “right the wrong” by adjusting payouts to what they would have been had the accounting error not happened in the first place.

3. Pressure-test the reasonableness of a methodology given the case’s unique facts and circumstances.

Be wary of cookie-cutter techniques for measuring erroneously awarded compensation in the context of a market metric. If you’ve seen one restatement, you’ve seen one restatement. In all cases, the facts, timing, stock price movements, and information set will differ. Any analysis must put the facts and circumstances of the case under a microscope.

Even a robust technique, such as an event study or fundamentals analysis, will be deeply vulnerable if performed generically and not applied to the fact pattern at hand. A generically, haphazardly deployed approach can overstate or understate recoverable compensation. More often than not, however, it will overstate the monies to be recovered because it won’t adjust for confounding factors that aren’t punishable under the SEC’s clawback framework.

This is ironic because the bigger worry is that the analysis is gamed to minimize the clawback. That’s a valid risk, and any analysis must be unassailable in its objectivity. However, we’re more concerned that specialists who are broadly trained in running event studies, but not as well versed in the Dodd-Frank clawback rule, may construct an analysis that is overly punitive and goes in excess of what the rule is specifically trying to accomplish.

4. Before diving into the heavy-duty financial and statistical modeling, identify the awards subject to clawback and the breakpoints at which payouts would be degraded.

Start by determining which awards are at risk and which are safe. This will bring clarity and concreteness to the exercise.

First, collect all the awards to the covered employees over the applicable lookback period. Given the October 2, 2023 effective date, initially this won’t include many awards or individuals. But the pool will grow over time.

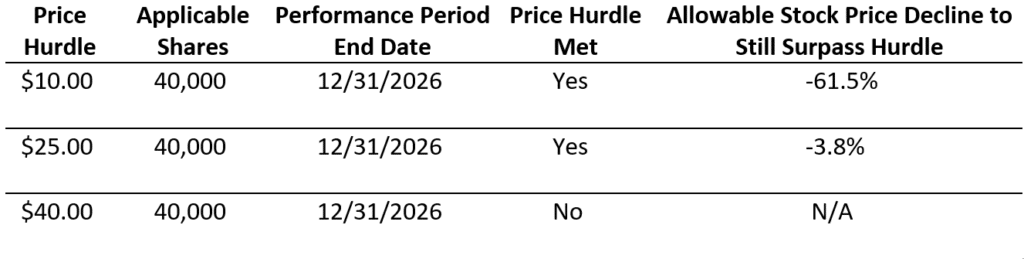

Second, for each award and tranche therein, calculate the maximum stock price reduction that would allow that award to remain unaffected by the recovery analysis. Using the adjusted (but-for) stock price, determine the highest price at which each award tranche would not be affected by the analysis. We call this the breakpoint because it signifies where a payout is first affected by the recovery analysis.

Different award designs will have different sensitivities and breakpoints:

- Binary payouts versus payout grids. Many absolute TSR (aTSR) awards come in the form of a series of tranches that are either earned or not earned based on reaching a stock price watermark. In contrast, relative TSR (rTSR) awards usually come in the form of a single tranche with a payout scale that ranges from 0% to 150% or 200%

- Step versus interpolation payouts. Awards with linear interpolation (most common, especially with rTSR designs) will be extremely sensitive to a recovery analysis. In contrast, with step function payouts, the market metric only adjusts the payout at discrete intervals

- Continuous versus point-in-time measurement. Some awards measure performance as of a single date, such as the end of the fiscal year, whereas others specify a window of time during which a metric can be achieved. Point-in-time measurement cases will obviously be most sensitive

This analysis tells you a lot about the problem at hand. For example, if a price hurdle award vested at a watermark of $10 and the stock price continued to run up to $26 during the performance period, the award is likely to be unaffected by the restatement. The breakpoint is $10 because there’s a binary payout structure at $10, but the stock price grew well in excess of the breakpoint. Then again, another tranche requiring a stock price of $25 may be in serious jeopardy. Here’s a visual depiction of such a breakpoint analysis:

With an rTSR design and linear interpolation, any percentile change is a breakpoint. However, the drop from above threshold (e.g., 25th percentile) to below threshold (e.g., 24th percentile) could cover a much larger impact on payout. If the rTSR design uses a step function, the breakpoint will be less sensitive.

You might be wondering how this even makes sense for an rTSR award with linear interpolation since virtually any stock price revision will impact the payout. In this context, the analysis gives you a sensitivity factor equating a $1 stock price drop to an X% payout drop. As we’ll discuss later, the recovery analysis won’t automatically give rise to an adjusted stock price (that’s different from the stock price used to calculate the payouts in the past). The statistics behind the analysis may conclude there’s not adequate evidence that the stock price would have behaved differently had the correct numbers been reported all along.

Event Studies (Top-Down Methods)

5. The parallel universe produced by a recovery analysis applies only to the exercise of measuring final performance and payout outcomes.

When a restatement spans many fiscal years, it may encompass not only when performance was measured, but also the grant date. Naturally the question will arise as to what the grants would have looked like if the stock price was lower at the issuance date—in other words, how liberal can the analysis be in the parallel universe constructed? For example, if the adjusted stock price is 20% lower, then ostensibly one or more of the following applies:

- More stock could have been granted at a fixed value

- The starting price point would have been lower

- The hurdle prices may have been set lower

While the logic makes sense, and board members often ask about it, we don’t believe it’s actionable. The intent of the rule is to accept the grant as is and to focus on the outcomes. Consistent with this, the language in the rule doesn’t permit an open-ended construction of a parallel universe. Rather, it hones in on the calculations performed at the time compensation was received.

For example, Section 10D-1(b)(1)(i) emphasizes the “recovery policy must apply to all incentive-based compensation received by a person…” Received is a defined term and refers to when the performance period is completed and the as-of date in which performance is measured.

6. Don’t draw sweeping stock price conclusions without studying the stock price (which usually will involve an event study).

If a reasonable estimate is the standard of care, does this imply a particular method is required? No, and the rule says as much. However, we believe that the move in stock price upon the market learning of the restatement (and release of correct financials)[1] must be considered in any analysis of a market metric. Typically, this is done using an event study.

In economics, an event study is a statistical method used to assess the impact of a specific event on the value of a company, typically by analyzing the event’s effects on the company’s stock price. You develop an event study to compare the stock price movements before and after the event to expected movements, thereby isolating the event’s influence from overall market trends.[2]

With many restatements, it’s easy to look at the change in financials and say, “These are small numbers that shouldn’t matter” or “The restatement didn’t touch revenue, which is all our investors care about.” There’s any number of qualitative assessments—including quite reasonable ones—that can be drawn. While conclusions like these may ultimately be accurate, it’s tenuous to make bold statements about the stock price without looking at the stock price. Event studies may not always deliver the most appropriate conclusion, but it’s hard to imagine performing a recovery analysis without running some sort of event study.

Even so, as we’ll discuss later, an event study may not be the best tool for every situation. For example, in section three of this paper, we discuss an alternative approach—fundamental analysis—which is a bottom-up means of quantifying how changes to earnings or cash flow mechanically should affect the stock price by using market-calibrated multiples.

7. Build the model iteratively to make sure you’re measuring what should be measured while filtering out irrelevant and confounding information.

Recovery analyses on market metrics are problems of information overload. This is true for both Big-R and little-r restatements. Let’s talk about each type separately.

In a Big-R restatement, the issuer files an Item 4.02 Non-Reliance disclosure, usually via a Form 8-K. Then there’s a multi-month lull as the issuer prepares new financials. The market is in a zone of suspense until new financials are released. The SEC cites sources showing that the average Big-R restatement impact on stock price is around 5%. However, we’ve seen announcements where the impact has been 30% or more.

Sometimes the stock price recovers partially or fully as the market realizes circumstances aren’t so bad. Other times, it stays the same or gets worse. So, while it’s important to study the stock price impact at announcement, it’s impossible to put the full picture together until the new financials are issued.

In any event, the task at hand is to combine the two discrete revelations of information while vacuuming out unrelated information during the same period. That is, the event study needs to consider the initial effect of the announcement, then it needs to fold in the conclusion when reissued financials are provided. It also needs to crowd out other good or bad news such as forward-looking guidance or product announcements by the company.

Unfortunately, reissued financials are often provided alongside unrelated news and announcements, which obviously have a confounding effect. We’ve used an iterative approach to tease out the moving parts and form a fuller picture of the restatement-specific effects.

Little-r restatements face the same problem. In a little-r restatement, there might not be an announcement that’s separate from the reissuance of financials. Moreover, the reissued financials are provided alongside new financials and forward-looking guidance. For example, if the little-r restatement is crammed into a release of FY 2025 financials, think about all the moving parts:

- FY 2025 financials, which are new and either meet, miss, or exceed analyst estimates (and may also embed a portion of the restatement in relation to previously released quarterly results)

- FY 2026 (and beyond) guidance, which also has an expectations component

- Revisions to FY 2023 and FY 2024 via the little-r restatement

- Other positive or negative surprises contained in the Form 10-K

Fortunately, with little-r restatements, the SEC cites academic research showing how the average stock price effect is about 0.3%. While this is hardly a substitute for a case-specific analysis, it provides corroborating evidence for a formal study that also concludes there’s minimal or no discernible impact from the restatement.

8. Study all value-relevant information revealed to the market, then parse out information unrelated to the updated results.

To determine the adjusted stock price, we need to account for any day in which investors might have inferred information about the existence and size of the restatement. For example, in addition to the date the 8-K and restated financials are released, dates could be important if:

- There’s a news release speculating on accounting irregularities

- The company announces the termination of the CFO and replacement of the auditor

- The company further delays filing of their restated financials

Remember, the goal is to link movements in the stock price to the restatement, so any date where the market gleans something about the restatement is potentially relevant to the value. We say potentially because the market may be latching on to something other than the restated results. After all, the market doesn’t even have the restated results in hand at the time of the announcement, only the knowledge that they cannot rely on the old numbers and new ones are on their way. For this reason, the measure of price inflation may change as the release date of new financials approaches.

Another potential scenario is a restatement of financials in the seemingly distant past. For example, imagine a restatement announced in 2024 where the company says that acquisition costs were recognized in 2022 but should have been recognized in 2021. It’s plausible that an analysis would show the stock price was inflated prior to the release of 2022 financials, but after that, the stock price was unaffected by the misstatement.

You might be wondering how this reasoning applies to little-r restatements. The problem with little-r restatements is that they necessarily get wrapped into one day; there usually aren’t discrete markers in the sand to analyze as there are for Big-R restatements. As such, there’s a lot of information for the market to digest, but only one piece of that information is relevant to the recovery analysis: the restated financials.

In these cases, we may rely even more on fundamental analysis (discussed shortly) and expand the regression model behind the event study to parse between the confounding pieces of information. We suspect the conclusion will often be that there’s nothing to recover because the effect of the little-r restatement is minimal, which is why it’s important that the SEC formally acknowledged this reality by citing academic research to corroborate it.

9. See what’s moving the stock price and when the market seems to fully incorporate the right information.

With a Big-R restatement, stock price movements should be studied as of the point of announcement all the way through—and often even extending past—the reissuance of financials. That period could last several months as the company sorts out accounting systems issues, hires outside consultants, etc.

We’ve seen cases where an initial, post-announcement drop in stock price reversed quickly, possibly because investors figured the situation wasn’t as bad as it seemed. On the other hand, investors often assume more bad news is on the way and may not change their minds for some time. So you should expect a strong reaction to the announcement, then be prepared for a variety of movement types during the ensuing weeks or months until the restated numbers are provided and the market can absorb them.

It’s reasonable to study stock price movements up to three months after the restatement when assessing the extent to which the price recovered.[3] However, since we’re often studying multiple dates—such as the initial announcement and subsequent restatement—we generally include the full period from announcement to reissuance. Then we allow for a moderate tail post-reissuance (say, one to two weeks). A tail that’s much longer risks pulling in unrelated events and information.

In contrast, with a little-r restatement, the period after the release of new financials is the only period available to study. While the longer we extend the analysis period the more confounding information can enter the equation, we also gain valuable data points to fold into the model and allow us to parse between restatement-specific effects and other effects. Here the 90-day bounce-back provision could provide an upper limit on how long of an analysis tail to permit.

10. After a clawback, look at the full terms and economics of the award and consider the possibility of the award being “re-earned” prior to the conclusion of the award’s performance period.

For price hurdle and certain other awards, it’s important to note there’s life after a restatement and a clawback. In this case, if the stock price recovers before the end of the performance period, we believe that any awards clawed back would still be eligible for “re-earning.”

For example, consider a five-year performance period governing an aTSR metric. The aTSR watermark is achieved after two years and a restatement is announced shortly thereafter. The earned aTSR awards are clawed back. However, in year four, the company’s stock price surges past the aTSR hurdle. The restatement is in the rear-view mirror and there’s nothing inflated about the stock price.

It’s hard to reasonably argue that stock price attainments post-restatement wouldn’t have been achieved absent the corrective disclosures. As we pointed out earlier, the SEC rule isn’t a punishment device; it’s a “make-right” device. Once the financials are made right, there should be nothing stopping awards from vesting that are still outstanding and eligible for vesting.

Fundamental Analysis (Bottom-Up Methods)

11. Test multiple analytical methodologies, then select the most appropriate one.

Event study and similar techniques are top-down methodologies in that they start with the overarching impact of the restatement and whittle away at any confounding and irrelevant information. But it’s impossible to know for certain whether all the confounding information has been removed.

The SEC’s standard of care is to develop a “reasonable estimate,” which suggests there isn’t a mandate to run many different analyses. However, doing so can be helpful when the results from a single analysis seem counterintuitive. For example, what if the event study shows a 30% stock price drop but the restatement involves reallocating earnings between two segments that are believed to be similarly valued by the market?

This is one of many instances where it may make sense to bring another methodology to the table. The goal is never to methodology shop, but to see how multiple analytical frameworks deal with the economics of the restatement.

One commonly accepted alternative involves fundamental analysis of the restated amounts. We call this a bottom-up analysis because a model is built that links the restated amounts to the stock price using valuation principles.

What if different techniques give different answers? We don’t think there’s any basis in the SEC rule that requires averaging multiple techniques. We believe the board, in collaboration with a firm like ours, should select the most appropriate one that it believes to be reasonable in light of the fact pattern. The other methodologies considered may or may not be referenced in the final report, but the final conclusion can certainly be based off the one methodology that’s deemed most appropriate.

12. Consider fundamentals analysis in addition to an event study.

A company’s fundamentals present a good opportunity to apply backward-looking logic to cut through the noise in the stock price movement. Specifically, we can apply pre-restatement stock price multiples to the restated financials to estimate the adjusted stock price. Especially when the restatement and vesting events are years in the past, fundamental analysis may even be a cleaner vehicle for sorting through the noise inherent in stock prices and top-down based methodologies.

As an example, imagine last year’s EBITDA was overstated by 5%. If we assume a constant EBITDA multiple, the result is that the stock price was inflated by the same amount. This approach is appealing in its simplicity. Still, if the result doesn’t tie to the stock price movement, we need a compelling theory for why.

The first key to a fundamentals analysis is to figure out what matters to investors. For a megacap with decades of operating history, earnings measures are likely going to be the most important. The same isn’t the case for a pre-revenue startup, where forecasts are much more important to investors than past financials.

Analyst reports and other investor news discussing stock price movements can be a valuable place to identify and confirm what matters most.

It’s important to consider whether this analysis with a constant multiple makes sense. If there’s a 1% drop in EBITDA, it’s probably reasonable to assume the change in stock price would be consistent. On the other hand, if EBITDA falls by 10%, this may imply something about the growth trajectory of the firm and result in a non-linear price adjustment by investors (e.g., they conclude the company isn’t a growth company deserving of a growth-oriented multiple).

Another factor to consider is that larger organizations may have different segments, making it important to drill down to segment levels when segment-level information is being restated. In one case, we developed separate segment-specific multiples for our bottom-up analysis, as earnings were shifted from a high-growth segment to a commodity segment, with no impact to the aggregate.

Best Practices and Success Factors

13. Run analyses under legal privilege to fully evaluate the issues and protect the company against pieces of the analysis being used in inappropriate and unintended ways.

Given the sheer number of moving parts and analytical possibilities, these studies should be performed under legal privilege. The goal of a study is to arrive at a reasonable estimate—plain and simple. However, you’ll likely explore alternative paths to arrive at this estimate. There may also be sensitive discussions taking place amid the chaos of sorting out the new financials and trying to filter out confounding information.

For all these reasons, the analysis performed should be privileged. Typically, legal counsel to the board of directors will engage us as part of its broader effort to guide the board in arriving at a complete Dodd-Frank recovery analysis.

14. Take a phased, multi-step approach to any analysis.

With market metrics, information will evolve dynamically as the recovery analysis unfolds. Consider taking an iterative approach that begins as soon as the decision is made to restate financials.[4] This means the analysis must begin before the story has run its full course. However, it allows both us (the specialist) and the board to begin identifying the key issues and variables at play.

In addition to starting the analysis at the point of initial announcement, which may precede the formal reissuance of financials, we also separate probing from pressure-testing (or what we’ve referred to as level 1 and level 2 analyses). This phased approach allows the board to come on the journey and ask questions along the way, instead of having to take in an exhaustive report all at once.

The difference between the two levels of analysis is that level 2, the deeper analysis, will pressure-test the basic conclusions and assess whether there are alternate explanations. For example, this may be where a fundamental analysis gets layered in. Or, this may be where the event study is refined to consider whether part of the stock price drop is linked to something other than the new numbers, such as negative signaling about future earnings.

15. Tailor your documentation and analysis to each audience

Remember you have at least two direct audiences: the board of directors and the listing exchange (which includes the SEC given they maintain the ability to review information filed with the listing exchange). Management is an indirect audience, not only because they’re affected by the results, but also because they’re responsible for disclosing details on the clawback enforcement in the proxy and potentially supplying data during the analysis.

Since the board is accountable for the conclusions in the final recovery analysis, they’ll want to understand the process as well as the strengths and weaknesses of each analytical framework. It matters how you walk them through the analysis given how dense and technical the topic is. In general, board members appreciate plain language and interaction that allows them to come up to speed. So, avoid delivering the kind of expert report you might see in litigation. Instead, treat board-facing materials like any other compensation-related update they receive: a few pages explaining the issue, the parameters, and the decision points. Follow these with a moderately-sized appendix containing supporting analysis.

In addition to board-facing materials, a report must be filed with the listing exchange documenting the final conclusion, methodology, and key assumptions. This doesn’t necessarily need to be at the depth of a litigation-related expert report. But it should be clearly organized and focus on explaining the methodology, why it was selected, and why it delivers a reasonable estimate in light of the fact pattern.

Finally, remember the proxy requires comprehensive disclosure as to the clawback amounts, the assumptions in determining these amounts, and the company’s progress toward recovery. The language should be clear and complete to demonstrate the board is responsibly discharging its obligations under the company’s clawback policy.

Parting Thoughts

The SEC’s Dodd-Frank clawback rule will only affect a small fraction of companies, but for those facing a restatement, this will add complexity to an already tense and high-stakes situation. The best first step is to develop a playbook today that guides the future project team on what steps to anticipate taking, which internal functions and external partners will drive the respective steps, and generally how to execute in the heat of the moment.

We are happy to be thought partners to SEC registrants and legal counsel on our experience, and of course if the unfortunate situation of a restatement transpires, don’t hesitate to reach out to us.

****************************************************

[1] In a Big-R restatement, these two events occur at different periods of time, whereas little-r restatements will often comingle the announcement of restated numbers with the restated numbers and many new forward-looking numbers.

[2] For more on how an event study works, you can read our discussion here.

[3] 90 days is used based on the bounce-back provision contained in the Public Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995.

[4] With a Big-R restatement, there’s most definitely a time gap between the announcement and reissuance of financials. With a little-r restatement, there may not be an announcement, and therefore only one event date to analyze.