How the SEC’s Latest C&DIs Impact Pay vs. Performance Disclosure Practices

Updated December 1, 2023

On September 27, the SEC issued a second batch of Compliance & Disclosure Interpretations (C&DIs) on pay vs. performance (PvP). Then, in a surprising turn of events, the SEC on November 21 modified certain C&DIs from both its September 27 and February 10 releases.

Although the September C&DIs contained long-awaited clarifications well ahead of proxy preparation cycles, our understanding is that there were concerns about the transition implications of some of those clarifications, especially around retirement eligibility. (Other topics from September, including option valuation and disclosure, were left untouched.)

This revised article covers both the September and November rounds of C&DIs, plus one of the C&DIs from February that the SEC also revised.

As we did last time, we’ll summarize each interpretation provided by the SEC, then share our reaction. But this time, our reaction will reflect the expected based on how practice unfolded during year one. We’ll also share the original and modified C&DI release dates.

If you’re mainly interested in the November updates, you can use the links below to jump directly to those C&DIs.

Question 128D.07: peer group changes (original: Feb 2023)

Question 128D.18: retirement eligibility (original: Sept 2023)

The following eight C&DIs are new as of November:

Question 128D.23

Question 128D.24

Question 128D.25

Question 128D.26

Question 128D.27

Question 128D.28

Question 128D.29

Question 128D.30

Topic-By-Topic Review of the C&DIs and Our Perspectives

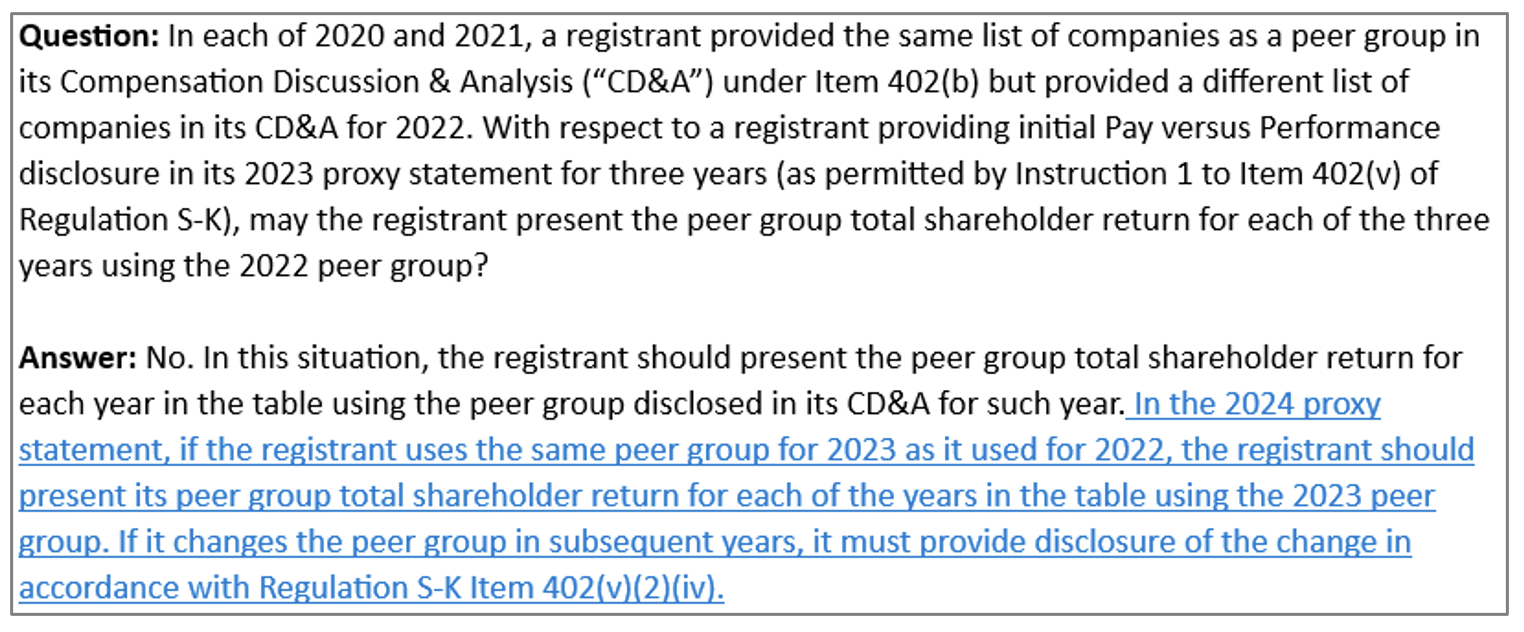

Question 128D.07

Release date: February 10, 2023; modified November 21, 2023

Question summary: If using the Compensation Discussion and Analysis (CD&A) peer group to calculate peer total shareholder return (TSR), can the fiscal year 2022 peer group be used for all three years of the initial disclosure? Or must the peer groups used in fiscal years 2020 and 2021 be used for those respective years’ peer TSR calculations? For disclosures after the initial one (e.g., for the 2024 proxy), should different peer groups be used for each respective year in which a different CD&A peer group exists?

Answer summary: We think reasonable people can read this one differently. Take a look at the November addition to the original February text.

For the initial year 1 disclosure, the SEC required using the peer group applicable to each fiscal year as the basis for the peer TSR calculation in each respective year. For example, if peer groups A, B, and C were in place during fiscal years 2020, 2021, and 2022 respectively, then peer group A is used for the fiscal year 2020 calculation, group B for the fiscal year 2021 calculation, and group C for the fiscal year 2022 calculation.

This February guidance triggered concern because it appeared to contradict guidance in the original rule release, which indicated that only the latest peer group should be used. We believe the November C&DI brings practice back into alignment with the original release by stratifying the special treatment applied in the year one disclosure from all future disclosures. In future disclosures, the most current peer group should be used to calculate TSR for all prior years in the table.

While this may appear cumbersome, TSR calculations are among the easiest to perform in this process. According to our research, about 20% of companies used a custom CD&A peer group instead of their Item 201(e) index.

Finally, remember the final rule requires footnote disclosure of what the peer TSR calculation would have been under the old peer group.

Impact on practice: minimal.

On balance, this is a net improvement because it standardizes the peer group behind the values from the different years in the table. Under the February guidance for year one, the fiscal year 2020 row could be stemming from peer group A and the fiscal year 2021 row could be stemming from peer group B—and those two peer groups could be vastly different. Even though the updated guidance requires recalculating TSR for prior fiscal years, this isn’t hard to do and yields incremental harmonization across years.

Question 128D.14

Release date: September 27, 2023

Question summary: Should awards converted in a spinoff or similar transaction (awards granted pre-transaction) be included in the PvP calculations?

Answer summary: Yes. According to the SEC, if those awards are outstanding and unvested, and ASC 718 expense is still being recognized by the post-restructuring issuer, then they should be included like any other award.

Impact on practice: minimal.

Awards that are converted in a spinout or assumed in an acquisition are functionally just like any other award. Companies recognize them in the financial statements and pay for them via the terms of the transaction and employee matters agreement.

Question 128D.15

Release date: September 27, 2023

Question summary: For companies that went public (e.g., due to IPO, direct listing, or de-SPAC) during the PvP covered period, should the initial compensation actually paid (CAP) valuation for the fiscal year-end calculation component of awards outstanding prior to the public offering be based on a pre-public price or the price when the company began trading publicly?

Answer summary: The pre-public price (as of fiscal year-end) should be used.

Impact on practice: minimal.

It would be hard to compare PvP across companies if newly public companies could disregard the price at their prior fiscal year-end in lieu of their go-public stock price.

The argument against using a pre-public price is that these are theoretical and often differ from the starting public company price. However, leaning into this view would be admitting defeat—the SEC has long been focused on addressing “cheap stock” problems and shoring up private company business valuations.

An additional comparability challenge this raises is the disconnect between the period over which CAP is measured (the full year, even pre-public) and when TSR is measured (beginning on the registration date, as specified in Question 128D.06). This is arguably the least problematic of the available alternatives, as using a shorter CAP period or longer TSR period would have their own substantive issues. Nonetheless, companies in this situation should be aware of the timing difference, which can cause nonintuitive results comparing pay and performance and might warrant some explanatory disclosure.

Question 128D.16

Release date: September 27, 2023

Question summary: Should market conditions be incorporated in the CAP valuations given they’re not formally defined as vesting conditions under ASC 718?

Answer summary: Yes. But there’s also a secondary nugget of insight in the SEC’s response. The SEC writes:

Similarly, registrants must deduct the amount of the fair value at the end of the prior fiscal year for awards that fail to meet the market condition during the covered fiscal year if it results in forfeiture of the award.

Impact on practice: minimal.

ASC 718 states that market conditions aren’t vesting conditions, which helps FASB achieve two goals:

- Ensure the economic effect of market conditions is embedded in the fair value

- Block companies from reversing expense when market conditions aren’t achieved

In the domain of ASC 718 accounting, compensation cost is not reversed upon failure to achieve a market condition because the valuation of that condition already contemplates the probability of failure.

The SEC says that “market conditions should also be considered in determining whether the vesting conditions of share-based awards have been met” because market conditions can trigger vesting events. For example, an award may have a price vesting hurdle after three years and a one-year service tail on the back end. If the market condition isn’t achieved, then the award may cancel and the service condition no longer matters.

In summary, so long as awards with market conditions are outstanding and unvested with a probability of attainment, they have value. As a result, they need to be valued pursuant to the framework in ASC 718, just as they would at the date of grant. This involves developing a valuation model (usually Monte Carlo simulation) and refreshing that model based on evolutions in the stock price and other model inputs.

The secondary point the SEC raises is where in the PvP reconciliation table to allocate forfeitures that stem from market and performance conditions not being met. This doesn’t affect the overall calculation of CAP, but rather, which row in the breakout table the outcome is applied to. The SEC’s response seems to suggest running a $0 payout outcome through the row for “any awards that fail to meet the applicable vesting conditions during the covered year” (Item 402(v)(2)(iii)(C)(1)(v)).

An alternative interpretation would say the award vested insofar as the requisite service was rendered, but the value of the consideration delivered is $0 (under this interpretation, you would run the result through the preceding reconciliation table swim lane for “change in fair value of awards granted in a prior fiscal year for which all applicable vesting conditions were satisfied at the end of or during the covered fiscal year” (Item 402(v)(2)(iii)(C)(1)(iv)).

The wrinkle with the interpretation taken is that a 1% payout will run through the later swim lane (iv) whereas a 0% payout will run through the former swim lane (v). Given the possibility for confusion and optically counterintuitive values in the reconciliation table, this is worth discussing internally and with legal counsel if it appears an award is trending toward a zero value payout.

Question 128D.17

Release date: September 27, 2023

Question summary: Should awards that fail to vest in a year due to a market or performance condition, but still have a future vesting opportunity, be zeroed out in the CAP calculations?

Answer summary: No. An award should be zeroed out in the CAP calculations only when its definitive, final value is zero (e.g., due to a forfeiture or performance/market conditions that caused it to settle at a zero dollar value). As long as there’s a future opportunity for the award to vest, it should remain in the CAP calculations and be remeasured as of fiscal year-end via the customary process.

Impact on practice: minimal.

Remember, there are six components to the CAP calculation. Awards that are unvested and outstanding as of the fiscal year-end are valued as of that date, and that value is compared to the value at the prior fiscal year end. If a performance or market condition has not been achieved by fiscal year-end but can still be earned in a subsequent period, then the award simply continues to flow through the calculation normally, even if the fair value is at or near zero on the calculation date.

It’s important to return to the intent of the rule: The CAP calculation is simply a process for marking-to-market awards from grant to eventual extinguishment. When an award is extinguished, it hits the calculation one last time and then drops out. (And it hits the calculation at its final realized value, which can be zero or a positive amount depending on how market and performance conditions play out.)

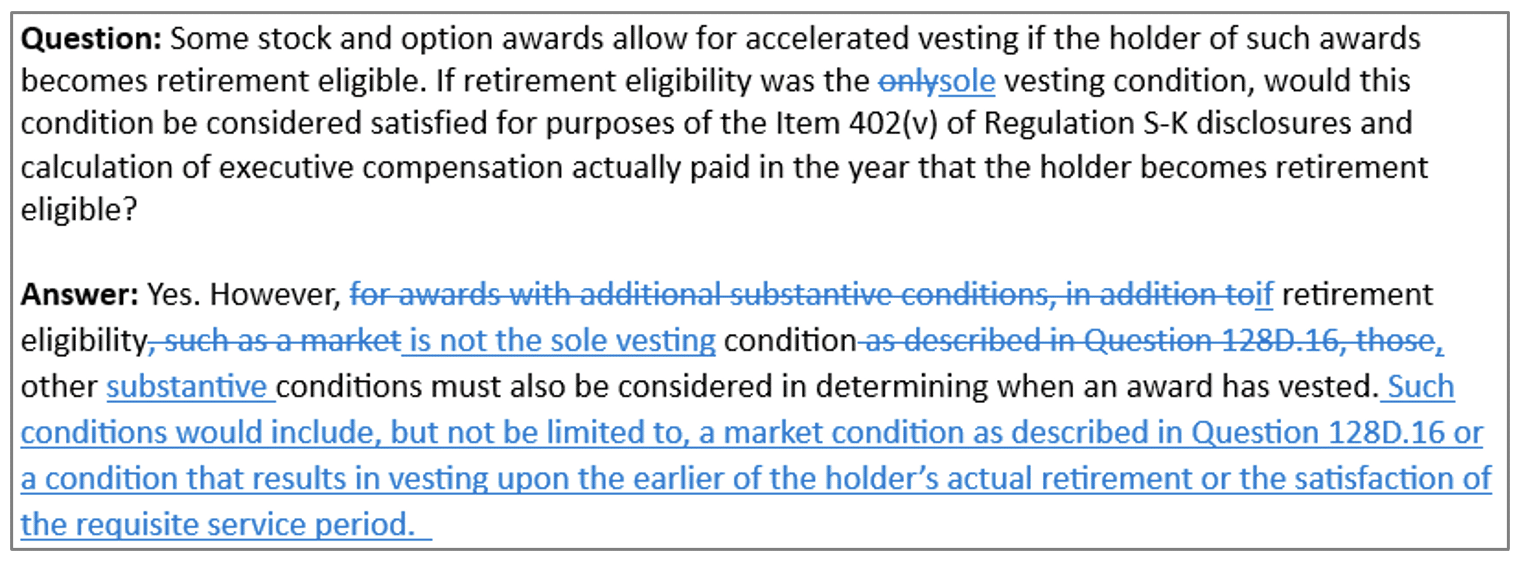

Question 128D.18

Release date: September 27, 2023; modified November 21, 2023

Question summary: Is an award considered vested for PvP purposes when the holder achieves retirement eligible (RE) status on an award with a standard time-based vesting schedule (which, for accounting purposes, is when the award is considered fully earned)?

Answer summary: No. This November answer seems to be a reversal from the September guidance. As of the November guidance, the legal vesting date evidently should serve as the basis for considering an award vested for PvP purposes, not the “accounting vesting date” as per any retirement eligibility provisions. That said, the SEC did not come out and directly say they changed their position, so our view is based on both the context of the new guidance and dialogue within the industry. Here’s a redline of the September language based on the newer November language:

Swapping “only” for “sole” and adding the last sentence to the answer changes the game. Although retirement eligibility provisions come in all shapes and sizes, a thread running through virtually all structures is that an employee may earn their awards in one of two ways. The first is by rendering service through the stated vesting period. The second way is by choosing to retire after reaching some age and service threshold (e.g., 55 years of age and 10 years of service). We call this a “dual vesting structure.”[1]

A “mono vesting” structure would be one in which the only way an award is considered vested is when an employee reaches a specified age and service threshold. That’s the only pathway to vesting. We almost never see these mono (what the SEC calls “sole”) structures in practice. Conceptually, they would be lifetime awards that vest upon a mandatory retirement threshold.

What took us by surprise is the actual wording of the C&DI. The C&DI affirmatively answers with regard to an outlier case, then negates that methodology for the vast majority of cases seen in practice—that is, the cases with the traditional dual vesting structure that the newly added final sentence explicitly references.

How and why is the SEC rejecting the use of the retirement eligibility date as the basis for vesting in the CAP calculations?

The C&DI question asks whether an award where retirement eligibility is literally the only vesting condition should be considered vested on the retirement eligibility date. The answer is yes. But what about awards with other conditions? The SEC says those other conditions should be considered, citing two examples. One is an award that contains a retirement eligibility provision alongside a market (or, by extension, performance) condition. There’s nothing controversial there.

The other example is a reference to the classic dual vesting structure. Under a dual vesting structure, there’s a stated legal vesting date that postdates the retirement eligibility date. This secondary condition gives cover to consider the award to not be vested (for CAP purposes) until the legal vesting date.

Still, the language may leave room for interpretation. For example, if the employee retires and there are no residual performance or market conditions, should this be considered an acceleration of vesting? After all, the employee isn’t rendering any additional service yet has captured their award. We can argue this both ways. On the one hand, there’s no service left to render. On the other hand, the award’s provisions still point to a future property transfer event on the legal vesting date. So long as the legal vesting date and transfer of property will occur in the future, it seems reasonable to continue viewing that as the vesting date for CAP purposes.

Given this ambiguity, we suggest being consistent with the approach taken in the Stock Vested and Options Exercised table.

Why did the SEC change its views on this issue between September and November?

During year one, most companies treated the legal vesting date as the basis for their CAP calculations. The best argument for doing so was prior informal interpretive guidance the SEC provided in 2014 with regard to the Option Exercises and Stock Vested table. Even though the purpose of that table and PvP differ, there seemed to be value to consistency in the absence of a compelling and explicit reason to introduce different frameworks. Additionally, using the retirement eligibility date as the basis for vesting would make it difficult to have comparability between organizations (although there are other factors also complicating comparability).

Therefore, the September guidance introduced a relatively large pivot to the industry. Since automation lies at the heart of everything we do, we weren’t concerned about the methodology change itself. But we did struggle with the lack of clarity on whether companies should adopt the new guidance prospectively or retrospectively.

Our understanding is that these practical transition concerns were taken to the SEC. With its November rewrite, the SEC may be trying to give companies relief by letting them resume using the legal vesting date approach.

Is there a different way to read the C&DI?

Yes. C&DIs are written by the Division of Corporation Finance (Corp Fin for short). Corp Fin has strong accounting expertise and obviously can draw on the Office of the Chief Accountant, but it doesn’t ordinarily delve as deeply into technical accounting standard-setting. Corp Fin’s focus is much more on the practicality, usability, and potential abuse of disclosure practices. Our worry is that the November guidance uses a term of art from ASC 718—requisite service period—without necessarily considering how that term of art is used the technical gallows of ASC 718 financial reporting.

Let’s look at the November C&DI guidance (our paraphrasing):

If retirement eligibility is not the sole vesting condition, other substantive conditions must also be considered in determining when an award has vested. This would include a condition that results in vesting upon the earlier of the holder’s actual retirement or the satisfaction of the requisite service period.

When you read the guidance this way, the first question is: Okay, what’s the requisite service period?

To answer that, we need to go to ASC 718. ASC 718-10-55-67 states that:

The requisite service period for an award that has only a service condition is presumed to be the vesting period, unless there is clear evidence to the contrary. The requisite service period shall be estimated based on an analysis of the terms of the award and other relevant facts and circumstances, including co existing employment agreements and an entity’s past practices; that estimate shall ignore nonsubstantive vesting conditions.

Awards may contain explicit, implicit, or derived service periods corresponding to time-based service requirements, performance conditions, and market conditions respectively. When multiple conditions exist, the requisite service period is the minimum of the explicit, implicit, and derived service periods if only one needs to be achieved, and it’s the maximum if they all need to be achieved (ASC 717-10-55-73).

How about a time-based award (i.e., no performance or market conditions) that’s subject to a retirement eligibility provision? Let’s look at ASC 718-10-55-87 and 88:

Assume that Entity A uses a point system for retirement. An employee who accumulates 60 points becomes eligible to retire with certain benefits, including the retention of any nonvested share-based payment awards for their remaining contractual life, even if another explicit service condition has not been satisfied. In this case, the point system effectively accelerates vesting. On January 1, 20X5, an employee receives at-the-money options on 100 shares of Entity A’s stock. All options vest at the end of 3 years of service and have a 10-year contractual term. At the grant date, the employee has 60 points and, therefore, is eligible to retire at any time.

Because the employee is eligible to retire at the grant date, the award’s explicit service condition is nonsubstantive. Consequently, Entity A has granted an award that does not contain a service condition for vesting, that is, the award is effectively vested, and thus, the award’s entire fair value should be recognized as compensation cost on the grant date. All of the terms of a share-based payment award and other relevant facts and circumstances must be analyzed when determining the requisite service period.

The example is stating that the requisite service period on this award is zero years because the explicit service period is nonsubstantive and the requisite service period “shall ignore nonsubstantive vesting conditions” (ASC 718-10-55-67, quoted above).

Now back to the November C&DI. When the SEC says to look at the interplay of the actual retirement date and requisite service period, a textual reading of ASC 718 would suggest the requisite service period is the date of retirement eligibility. If that’s true, then we wind up right back where we were in the September guidance, that the vesting date is the retirement eligibility date.

We genuinely believe the SEC was trying to revise its guidance to emphasize the legal vesting date. But in doing so, they used a term of art (the requisite service period) that could lead to a different conclusion. We go into this level of detail because we believe the literal text in the C&DI could be used to support both viewpoints. Still, our general guidance in light of the broader context is to use the legal vesting date.

Impact on practice: significant relief from the updated November guidance.

When the September guidance came out, we didn’t disagree on technical grounds. Our main concern was the transition implications. As noted, most companies in their year one disclosures adopted the first or second of the three available alternatives for handling retirement eligibility:

- Ignore retirement eligibility and use the legal vesting date (point of property transfer)

- Use the legal vesting date unless the executive retires pursuant to the retirement eligibility provision, in which case the retirement date is used

- Use the retirement eligibility date

Since most companies didn’t previously use the approach prescribed by the September guidance, this introduced a transition decision of whether to adopt the new guidance prospectively or retrospectively.

If the new November guidance effectively affirms approaches one or two, then this transition question remains. But now it affects companies that have been using the retirement eligibility date as their basis for vesting in determining CAP. This is a much smaller subset of companies.

Does the SEC’s new guidance permit use of the retirement eligibility date? We’re not sure, which is why we laid out the affirmative argument based on how the requisite service period is a unique term of art in ASC 718. We believe further clarification from the SEC on this would be helpful.

If the retirement eligibility date was used, and the company concludes that it’s no longer appropriate in light of the November C&DI language, then the company needs to make a prospective-versus-retrospective decision. But the SEC hasn’t clarified whether methodology changes should be applied retrospectively or prospectively (i.e., only for future disclosures).

It’s not obvious how to make this change only prospectively. The simplest approach is to leave prior-year values untouched and apply the SEC’s clarified methodology to fiscal year 2023 without any cumulative catch-up for the prior years. The downside to this approach is that the years won’t roll cleanly into the back-end calculations and comparability will suffer.

Another approach is to take a cumulative catch-up in 2023 for awards that were previously treated as vested (because they were retirement eligible) but no longer are under the new interpretation.

Retrospective adoption is the cleanest approach, because it involves recalculating all prior year values, but for this reason it involves the most rework. Another con is that the year two table won’t match the year one table and may require additional disclosure to explain.

Stepping back, it isn’t clear whether alternative approaches used pre-C&DI are incorrect or the C&DI is simply offering a better approach going forward. Also, as discussed, it isn’t clear whether the SEC is stating that the retirement eligibility date is a prima facie wrong answer or that companies have some discretion to apply in determining what they think the most appropriate vesting date is for PvP purposes.

Question 128D.19

Release date: September 27, 2023

Question summary: If a performance or market condition is measured as of a certain date (e.g., fiscal year-end) but the certification by the compensation committee occurs later, is the award considered vested as of fiscal year-end?

Answer summary: It depends. If there’s definitively no additional service required after fiscal year-end, then the award is considered vested at fiscal year-end. But if service is required through the date of compensation committee certification or some date following that certification, then the SEC says that later date is the formal vesting date.

Impact on practice: minimal.

The vesting date is when all service, performance, and market conditions have been satisfied. If an executive passes the performance measurement date and leaves prior to the certification date, and this results in forfeiture, then clearly the certification date is the final vesting date. If not, then the performance end date is the final vesting date. Be sure to carefully evaluate the interaction of these provisions in your award agreement.

Question 128D.20

Release date: September 27, 2023

Question summary: For valuing options or stock appreciation rights (SARs), can the valuation methodology used for PvP purposes differ from that used at the time of grant?

Answer summary: Yes. However, the SEC qualifies this:

A change in valuation technique from the technique used at the grant date of such equity awards in the registrant’s financial statements would require disclosure of the change if such technique differs materially. We would expect a registrant to disclose under Item 402(v)(4) both the change in valuation technique from the grant date and the reason for the change.

Impact on practice: minimal.

The framework underpinning ASC 718 is to pick the best valuation technique for the job at hand. This is why many companies use Black-Scholes for new option grants but lattice and Monte Carlo models for other awards and circumstances when appropriate. (The framework is explicitly discussed in ASC 718-10-55-20 and ASC 718-10-55-17.[2]) In this sense, the SEC isn’t altering practice, merely reiterating the longstanding generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) that have always been in place.

Where the SEC’s comments are most interesting is around the disclosure requirement and how one would define “materially.” Materiality can be considered quantitatively or qualitatively. The numbers will undoubtedly differ from those at grant due to the passage of time, so contextually, a qualitative comparison is likely to be more relevant when determining materiality.

It’s not obvious how to qualitatively contrast a valuation technique used for PvP with that used for fresh new grants. A full-blown lattice model is paradigmatically different from Black-Scholes, so this would probably qualify as materially different. There’s also the “reverse footnote 55” method which relies on a lattice model but its inputs are calibrated using the grant date valuation from Black-Scholes.[3] We don’t think this is paradigmatically different because the lattice model is merely a vehicle for modeling exercise behavior in the context of the difference between the strike price and fair market value of the stock (commonly referred to as “moneyness”), but the method through which this is done links directly back to the grant date valuation.

Be careful, because it’s possible to retain Black-Scholes but develop the inputs in a way that’s materially different from the framework adopted at grant. For example, some companies may appeal to certain IRS guidance applicable to valuing options in golden parachute payments. IRS guidance is not GAAP. In fact, tax and accounting rules tend to differ more often than they agree, and certain types of tax valuations are clearly not compliant with GAAP.[4]

The bright line test we think makes the most sense is to consider what you would do if a new grant was being issued using the same moneyness and remaining contractual term as the grants being valued for PvP purposes. (Obviously, this wouldn’t happen in practice and would trip IRC Section 409A if the options are in the money, but it’s probably the right thought experiment.) In this thought experiment, to what extent would the company need to scrap its existing valuation approach for something altogether different? Of course, it would need to consider the different moneyness levels, but this could be done with minor adjustments to the existing approach without wholly abandoning that approach. We suggest evaluating the model in this way to arrive at a materiality determination, which then governs whether separate disclosure is necessary.

We would expect two key features in any ASC 718-compliant model. First, holding moneyness constant, as time passes, the remaining expected term of the option should be lower since there is less time left. Second, holding time constant, the option life should be longer for an out-of-the-money option than an in-the-money option since the former will require additional time to reach an exercisable level after vest.

Let’s apply the theory. One potential approach is to use a lattice model. Using our bright line test, this is materially different from the existing Black-Scholes methodology used at grant, so it would require separate disclosure.[5] In contrast, there’s a technique involving the elapsed term with targeted adjustments based on moneyness.[6] This preserves the framework at grant and folds in specific adjustments reflecting new information revealed over time. As such, this method probably wouldn’t require separate disclosure because it doesn’t materially differ from what was used at grant.

Question 128D.21

Release date: September 27, 2023

Question summary: Can options (or other option-like instruments) be valued using a methodology that isn’t consistent with GAAP?

Answer summary: No. The SEC specifically focuses its commentary on two approaches:

SEC simplified method of SAB 14.D.2. Consistent with the existing framework for applying the popular simplified method, the C&DI rejects its use for options that do not meet the “plain vanilla” criteria, one of which is that the options are at the money. Since it’s virtually impossible that options being revalued for PvP purposes will be at the money, it’s equally implausible that the simplified method will ever be permissible.

Elapsed term method. This approach involves starting with the expected term assumed at grant and subtracting the passage of time. The C&DI says that:

For example, the expected term assumption to value options should not be determined using a method that is not acceptable under GAAP, such as a “shortcut approach” that simply subtracts the elapsed actual life from the expected term assumption at the grant date. This approach would not be acceptable because it does not consider whether there were changes in the factors that a registrant considers in determining the expected term assumption at grant date, such as volatility and/or exercise behavior. U.S. GAAP fair value measurement objectives require that assumptions and measurement techniques be consistent with those that marketplace participants would likely use in determining an exchange price for the share options.

The guidance in this C&DI is substantially similar to nonauthoritative comments that Corp Fin’s chief accountant made back in December at the 2022 AICPA & CIMA Conference on Current SEC and PCAOB Developments.

Impact on practice: minimal for many, significant for others (i.e., certain heavy option granters).

We’re not at all surprised by the rejection of the simplified method as coined in SAB 14.D.2, as that guidance was intended from the outset to cover very different circumstances.

There are two ways we can interpret the SEC’s comments on the elapsed term method. The first is that it’s altogether prohibited, which is the interpretation drawn from reading the first sentence quoted above and stopping there. The second interpretation is that the elapsed term method should only be used if it can be shown to reflect how a marketplace participant would approach valuing these types of instruments. Our view is that the elapsed term method would often be compliant with GAAP if used with appropriate levels of consideration and not merely as a blunt and robotic shortcut. However, given the directness of the SEC’s comments, we anticipate guiding most companies away from using it without any adjustments that fold in consideration of evolutions in moneyness. We’re going to discuss this topic at length in the following subsections.

Background on Option Valuation

Six of the 10 academics cited in ASC 718 (back then, FAS 123R) were affiliates of our firm. The exposure draft to FAS 123R, released in March 2004, stated an explicit preference that options be valued using a lattice model. ASC 718, released in December 2004, backpedaled into an implicit preference for a lattice model while still allowing Black-Scholes. SAB 107 (now codified into SAB Topic 14), released in March 2005, removed even the implicit preference for a lattice model and explains why such a large majority of option granters use Black-Scholes.

ASC 718 and SAB 107 don’t say much about how to develop the expected term assumption in Black-Scholes. SAB 107 offers the simplified method, and ASC 718 says the expected term should take into account “both the contractual term of the option and the effects of employees’ expected exercise and post-vesting employment termination behavior” (ASC 718-10-55-19).

The most important reference in ASC 718 appears in ASC 718-10-55-31 in which FASB states the expected term should take into account the expected volatility of the underlying shares. In addition, “an entity also might consider whether the evolution of the share price affects an employee’s exercise behavior (for example, an employee may be more likely to exercise a share option shortly after it becomes in-the-money if the option had been out-of-the-money for a long period of time).”

Contextually, this last reference speaks to the use of a lattice model that contains a variable that adjusts the probability of exercise if an option surges into being in the money. In FAS 123R, it was a footnote (specifically, footnote 57) used as an example of how a company might consider moneyness. However, as Black-Scholes became the de facto standard in valuation, this level of advanced modeling was almost never used. This suggests there isn’t a bright line requirement in US GAAP to use a model that has a formal moneyness input, but rather, to consider the role of moneyness on exercise behavior. If this softer interpretation is correct, then there are many ways to do this by applying adjustments to the expected term in light of moneyness growth and contraction.

GAAP-Compliant Option Valuation

The SEC’s concern with the elapsed term method is that it ignores the evolution of the share price post-grant. For example, if the expected term were six years, one year has passed, and the share price fell 75% immediately after grant, it would be silly to assume a current expected term of five years. This would clash with how a marketplace participant would approach such a valuation exercise.

There are any number of things a marketplace participant might do. They could use a lattice model, but if the FASB believed this was the only thing they’d do, they would have retained their explicit preference to use a lattice model. A marketplace participant could assume the option will be held to its contractual term given its underwaterness.

We don’t think it would be absurd for a marketplace participant to consider the company’s volatility and conclude that an expected term at or above five years is still reasonable. After all, if the stock price fell so much it could certainly rebound just as much, especially over multiple years. Maybe an expected term of five years isn’t the best estimate, but we believe that a range of estimates between five and nine years could be reasonable, depending of course on the facts and circumstances.

What about a scenario in which the option reaches an in-the-money level of 2x during the year following grant (e.g., the strike price was $10 at grant and a year later the stock price is $20)? The elapsed term of five years would probably be considered quite reasonable by marketplace participants. They’d also stress much less over the expected term, since intrinsic value drives the option value more (and expected term matters less for value) as the option becomes more in the money.

Here’s what this boils down to: ASC 718 is a principles-based standard with few bright lines on expected term estimation. This is an artifact of the valuation politics of the early 2000s when numerous concessions were made from the purist academic views in the original exposure draft. We see nothing in ASC 718 that altogether repudiates an elapsed term method. Rather, we see a series of principles that challenge companies to evaluate the fact pattern and develop an expected term in light of that fact pattern.

Recommendations for Estimating Expected Term for PvP

The benefit of the elapsed term method is that it’s simple to apply and provides a reasonable estimate of fair value under normal evolutions in the share price. The downside is that it doesn’t take into consideration changes in moneyness, and therefore could give illogical outputs under various stock price movement scenarios.

This uncertainty as to whether the elapsed term will or will not yield reliable expected term estimates on a year-over-year basis leads us to suggest against its unadjusted use. This uncertainty undercuts the simplicity of the technique because testing would be needed to assess whether it remains appropriate in light of recent share price movements.

As discussed earlier, we generally consider three other methods:

- The reverse footnote 55 method

- An elapsed term with calculated adjustments for moneyness differences[7]

- A lattice model

We’re aware of some efforts to use crude IRS-prescribed methods, such as the approach in IRS Revenue Procedure 2003-68. There’s an even cruder approach in IRS Revenue Procedure 98-34. While these approaches are as easy to implement as many alternatives, we’re not convinced they satisfy the SEC’s litmus test of being GAAP-compliant. For example, IRS Revenue Procedure 2003-68 doesn’t distinguish between a 30% volatility and 65% volatility option, which flies in the face of ASC 718-10-55-31.

Remember, GAAP is developed by the FASB and may be clarified by the SEC. The IRS has absolutely no influence over GAAP and, as we mentioned already, GAAP and tax are generally viewed as diverged (there wouldn’t be book-tax temporary differences if the rules were converged; see all of ASC 740). IRS rules describe how options are valued for tax purposes (e.g., IRS Revenue Procedure 2003-68 states, “This revenue procedure applies only to the valuation for transfer tax purposes…”). Said differently, to the best of our knowledge, these techniques have never been used for financial reporting under ASC 718.

To close out this discussion, we’re not suggesting anything new here. All of these models have been used frequently with awards that lack plain-vanilla qualities, such as grants modified in an acquisition, options in an exchange program, and options that vest based on a range of performance hurdles. The difference is that those are higher-profile, one-time events where there’s a tacit expectation that a specialized or more advanced approach will be used.

Question 128D.22

Release date: September 27, 2023

Question summary: Since the PvP rules require footnote disclosure of assumptions made in the valuation process, and this includes expected payout outcomes on performance conditions, can issuers forego such disclosure if doing so would create competitive harm due to the confidential nature of these estimates?

Answer summary: Yes, the SEC is allowing the relief afforded by the competitive harm framework in Item 402(b) of Regulation S-K to apply to this disclosure. Consistent with other topics above, the SEC qualifies this by stating the registrant must provide as much information as possible without creating competitive harm, such as ranges of outcomes. The SEC also states there should be a discussion of how the change in the assumption affects how difficult it will be to achieve the targets.

Impact on practice: significant.

We think this response has some significant implications. It’s a positive development because it provides a means for not disclosing exact targets and progress against those targets. It’s possible that the use of wide ranges may result in disclosures that meet the SEC’s disclosure burden without divulging information that competitors couldn’t already infer from interim period financials.

On the other hand, this is easier said than done. Suppose a company is not on track to achieve its performance goals and the “range” truly is zero. In this event, it would be hard to comply with the softened PvP disclosure requirement without sending the negative signal that could create competitive harm. In this event, there is a zero-sum tradeoff between providing even a partial PvP disclosure pursuant to Item 402(v)(4) and the Item 402(b) framework on competitive harm.

There’s another implication that stems from the C&DI in that the SEC is reaffirming that assumption disclosure is important. According to our research, only 5% of PvP disclosures include tables containing the valuation assumptions underpinning the CAP calculations. Item 402(v)(4) requires disclosure of assumptions that “differ materially from those disclosed as of the grant date of such equity awards.” For options and market conditions, these are the inputs to the valuation technique. For performance conditions, this is the expected payout.

Most companies chose not to disclose any assumptions by adopting a liberal view of materiality in that assumptions are only materially different when an altogether different framework is adopted. Given the rhetoric in the C&DI, it appears as though the SEC might be taking a stricter or more literal view by suggesting material changes in the numbers themselves merit disclosure. We suggest closely watching this topic and how it evolves in practice.

Question 128D.23

Release date: November 21, 2023

Question summary: Should dividends or dividend equivalent units (DEUs) paid on the underlying shares prior to vesting be included in CAP?

Answer summary: Yes. This isn’t a change in the guidance at all. But it’s confused many practitioners since the conventional wisdom has been that the fair value of an equity award embeds dividends, therefore any separate inclusion of dividends is double counting.

The precise financial analysis is that the fair value of an award embeds the present value of all expected future cash flows and dividends. Suppose a company is trading at $50 a share on December 1, 20X3, then on December 2 declares a dividend of $5. December 2 is called the declaration date, and in tandem, the company specifies a future “record date” and “ex-dividend date.” All shareholders on the record date are entitled to the dividend, and those who buy the security afterward are not. The ex-dividend date is usually one day prior to the record date to accommodate the mechanics of T+1 settlement.

On the ex-dividend date, the stock price mechanically drops by an amount equal to the dividend. In our example above, the stock price would drop from $50 to $45 on the ex-dividend date. This is less obvious in practice since the market moves every day, but the fact pattern remains.

All this is to say that prior dividends paid are no longer embedded in the fair value of an award. The fair value reflects the present value of all expected future dividends, but not past dividends. Thus, when measuring an award’s value as of the end of a year, the prior dividends earned during that year must be added back to the value to avoid understating CAP.

Although the topic of dividends caused some heartburn, in our experience, companies have been applying the logic correctly and the C&DI isn’t altering any element of practice.

Question 128D.24

Release date: November 21, 2023

Question summary: When multiple indices are used in the Item 201(e) disclosure, is there flexibility in which one a company can select for its PvP TSR peer group?

Answer summary: Yes. The SEC carefully reiterates that the PvP rule only allows Item 201(e)(1)(ii) indices, which means broad indices are not permitted, only “published industry or line-of-business” indices.

The SEC goes on to state two additional expectations. First, companies that use multiple indices for Item 201(e) in the 10-K should clarify in their PvP disclosure which one they’re using for PvP. We believe this has been standard practice as the index is (and should be) clearly labeled in the PvP disclosure.

The second expectation is that when changing Item 201(e) indices, companies should disclose in a footnote the reason(s) for the change and what the results would have been had they used the previous year’s index. This clarifies that the treatment required for changes to the CD&A peer group should be mirrored when there are changes to the Item 201(e) peer group.

Impact on practice: minimal.

The original ruledidn’t make it entirely clear how changes in the Item 201(e) index should be flowed through. The November update fixes that. It also adds some extra work, but not much, as the TSR calculations are among the easiest to perform in this disclosure.

Question 128D.25

Release date: November 21, 2023

Question summary: Can a relative TSR peer group be used as the PvP peer group?

Answer summary: Yes, but only if the relative TSR peer group isn’t a broad-based equity index.

Question 128D.05 from the February C&DIs clarified that any peer group used for disclosure under Item 402(b) was permitted. That implied even a relative TSR award peer group could be used even though that kind of peer group isn’t officially being used for benchmarking purposes.

This C&DI implicitly reaffirms the usability of a relative TSR peer group. At the same time, it reiterates that the intent of Item 402(v)(2)(iv) is to use an industry or line-of-business index or peer group consistent with the spirit of Item 201(e)(1)(ii), and not a broad market index as described in Item 201(e)(1)(i). The SEC issued a comment letter emphasizing this distinction as well. Thus, a relative TSR peer group can be used if it’s an industry or line-of-business peer group, but not if it’s a broad-market index.

Impact on practice: moderate.

Very few companies used their relative TSR peer group in the first place (under 2%, according to our data collection). The bigger impact on practice is the more general clarification that broad market indices are not permissible, as many companies did use a broad index like the S&P 500 or Nasdaq 100 in their year one disclosure.

Question 128D.26

Release date: November 21, 2023

Question summary: In what circumstances is market capitalization weighting required for a PvP TSR peer group?

Answer summary: Whenever a custom peer group is used that’s not a published industry or line-of-business index pursuant to Item 201(e)(1)(ii).

Note that Item 201(e)(1)(ii) does allow the use of custom peers. Item 201(e)(1)(ii)(A) is where a published industry or line-of-business index is referenced, but (B) and (C) contemplate custom lists. This C&DI is clarifying that any custom list—whether it’s taken from Item 201(e) or the CD&A—must be market capitalization weighted.

We believe this has been the prevailing understanding and established techniques exist for performing the market capitalization weighting.

Question 128D.27

Release date: November 21, 2023

Question summary: In light of the requirement to footnote additions and subtractions to a custom peer group and disclose the before-and-after effects of the change, is there any situation where such disclosure is not required?

Answer summary: Yes. If the changes to the composition of the peers are due solely to pre-established objective criteria or a company is simply no longer in the applicable group (e.g., due to delisting), then the recalculation and footnote disclosure of TSR using the old peer group isn’t required. However, the SEC does expect disclosure of the change and its underlying reasons, in addition to the names of the companies removed from the new index or peer group.

Impact on practice: minimal.

Recalculating TSR using the old peer group has never been difficult given the role that computers and data feeds play in the overall process. We think this is still a good practice to perform, although now there’s flexibility to omit the result of the calculation in certain circumstances and simply provide a narrative discussion of the revision and its basis.

Question 128D.28

Release date: November 21, 2023

Question summary: If a company loses its smaller reporting company (SRC) status due to its public float during a year, can it provide the limited (“scaled”) SRC disclosures for PvP that year?

Answer summary: Yes. If a company ceases to be an SRC as of January 1, 20X4, then the scaled disclosures can be used for the 20X4 proxy (covering fiscal year 20X3). Future disclosures would need to provide the full PvP disclosure.

In transitioning, companies needn’t go back and calculate years that precede the date of their initial disclosure year. For example, if a company was an SRC in fiscal year 2022, their 2023 proxy would have covered only 2021 and 2022. Even if they’re not an SRC for 2023, they don’t need to go back and add 2020, even though other (long-time) non-SRCs’ disclosures include 2020. However, they’ll build up to containing a full five years in their PvP table, causing their PvP layout to eventually converge with those of companies that were never SRCs.

The SEC also clarified that prior years’ CAP figures in the table don’t need to be updated, as the named executive officers (NEOs) for those years remain fixed. However, the peer TSR and CSM figures—while newly required as a non-SRC—should be filled in for all rows of the table.

Impact on practice: minimal.

This will be the first year that companies run into this question, as the previous year’s disclosure was more straightforward with no year-to-year changes. The SEC’s clarification offers a practical way to handle the transition out of SRC status.

Question 128D.29

Release date: November 21, 2023

Question summary: If a company loses its emerging growth company (EGC) status, how many years of disclosure must it provide in its first PvP table?

Answer summary: Upon losing EGC status, a company must immediately begin providing PvP disclosures. However, it’s allowed to phase in the disclosure when newly subject to the rule, just as non-EGC companies could phase in their disclosures when the rule was new. For SRCs, this means two years of initial disclosure (building to three years). For non-SRCs, this means three years of initial disclosure (building to five years).

This is another question that companies will run into for the first time this year.

Question 128D.30

Release date: November 21, 2023

Question summary: If a company has two (or more) principal financial officers during a year, can they sum those two individuals’ CAP to compute the NEO average CAP?

Answer summary: No, the average is calculated based on each individual’s CAP, regardless of whether they occupied the same position for different parts of the year.

Impact on practice: minimal.

We understand the thinking behind the question, as the separate inclusion of outgoing and incoming executives can cause the NEO average CAP to swing nonintuitively. However, the rule seemed fairly clear as originally written, and our experience is that companies applied this correctly. Besides, summing the two executives’ pay can also produce nonintuitive results when considering new hire grants and the like.

A Clear Interest in Disclosure Quality and Accuracy

The SEC made a significant effort to understand where issuers and their advisors were struggling the most with PvP methodology and interpretive matters. The September 27 C&DIs go a long way toward tackling the items at the top of most companies’ hit lists, and the November C&DIs build on this.

Even so, questions remain. That’s expected with any new disclosure rule, especially one that has so many elements of a technical accounting standard—C&DIs would be 10 times longer if they filled in every last blank. ASC 718 itself relied on accounting firms and other industry experts to create institutional practices alongside the authoritative GAAP.

Where the proxy differs from financial reporting is that the proxy isn’t an audited document like the 10-K. So it will take longer for these sorts of institutional practices to ripple through the industry.

In any event, PvP has been a controversial rule given its speedy rollout. The worst is in the rear-view mirror, but PvP processes still need close attention because the SEC’s comment letters and C&DIs reveal an interest in disclosure quality and accuracy. Meanwhile, proxy advisors and institutional investors are developing models to assess and score PvP results, which will require high-quality analytics and clarity around PvP value drivers.

We’re in active dialogue with our hundreds of clients and broad swath of industry collaborators (consultants, lawyers, and accounting firms) on these topics. We’re happy to connect on any that are of interest to you.

[1] For ASC 718 accounting purposes, there’s nothing dual about the structure. Because the employee could choose to retire and not forfeit their awards upon achieving their retirement eligibility threshold, the accounting rules state the expense should be recognized over the truncated period ending on the retirement eligibility date. But, legally, the transfer of share ownership doesn’t occur until the stated vesting date or the date someone choose to retire (and is given their shares, as opposed to a “continued vesting” model). Certain taxes (specifically, US employment taxes) are due at retirement eligibility, whereas the rest are due at the transfer of share ownership. Therefore, we think of this as a dual structure since there’s activity at both the retirement eligibility date and legal vesting date.

[2] More specifically, ASC 718-10-55-20 states, “An entity shall change the valuation technique it uses to estimate fair value if it concludes that a different technique is likely to result in a better estimate of fair value,” and ASC 718-10-55-17 states, “The selection of an appropriate valuation technique or model will depend on the substantive characteristics of the instrument being valued…an entity may use a different valuation technique for each different type of instrument.”

[3] The Footnote 55 method was aptly named because FAS 123R has a footnote (55) explaining how one acceptable method for estimating expected term while preserving use of Black-Scholes was to calibrate a lattice model, drop the lattice model fair value into Black-Scholes, then back-solve for the expected term in Black-Scholes that yields that fair value. ASC 718 has no footnotes and footnote 55 was incorporated into the core text of ASC 718-10-55-30. The “reverse footnote 55” method is a variation in which we enter the grant-date fair value from Black-Scholes into a basic Hull-White lattice model, back-solve for the barrier that yields that fair value, then apply the lattice model to the options needing to be valued for PvP purposes.

[4] We’re aware of some views that the proxy disclosure on golden parachutes (Regulation S-K Item 402(T)) involves valuation of not-at-the-money options. That’s actually not the case. The SEC’s Instructions to Item 402(T)(2) simply require valuing options at their intrinsic value. There’s nothing from the SEC stating that the option valuation techniques used in drafting the Item 402(T) table are linked to fair value or, more generally, GAAP.

[5] Developing and using an altogether new lattice model is a material departure from a grant date method based on Black-Scholes. However, using the reverse footnote 55 method as described earlier probably would not be a material departure since it’s tethered to the grant date framework.

[6] As discussed here, the elapsed term method takes the original expected term and subtracts the number of years that have passed. On its own, this method is generally not GAAP-compliant because it doesn’t factor in moneyness. Variations exist that begin with an elapsed term and then apply targeted adjustments that are linked to moneyness. This would arguably not be a material departure from the grant date framework.

[7] Suffice it to say there are various approaches for implementing adjustments tied to moneyness. Some rely on simpler heuristics whereas others leverage corporate finance theory (e.g., cost of equity modeling) to formulate the adjustments.