Key Developments in 162(m) Regulation

Section 162(m) of the Internal Revenue Code remains a very challenging topic for corporate tax teams to manage. The regulation, which became effective in 1994, limits the deductibility of compensation for certain “covered employees” to $1 million each year. In 2017, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) materially changed the rules so that:

- The list of five covered employees must include the CFO (in addition to the CEO as before)

- Covered employees will always be covered, meaning those captured in previous years must be disclosed even if they are outside the top five in the current year

- Performance-based compensation is no longer exempt from the $1 million deductibility limit

- Public debt issuers and foreign private issuers are subject to 162(m) limitations

As the dust settled after the somewhat sudden passage of the TCJA, there was uncertainty around how to determine which awards would be grandfathered under the previous 162(m) rules. The TCJA stated a written binding contract would need to be in effect as of November 2, 2017. The presence of negative discretion—meaning the ability for compensation committees to unilaterally reduce payouts, which was widely included in award agreements and considered good governance—called into question whether a binding contract existed.

To address the impact of negative discretion, the IRS released Notice 2018-68 and submitted that only the portion of compensation that could not be unilaterally forfeited was eligible for grandfathering. However, inconsistency in interpretation and treatment remained even after the notice. Today, grandfathering is less of a concern for most companies since few awards granted before the effective date remain outstanding. (If this does affect your company and you still don’t have a formal resolution, we recommend discussing it with legal experts as soon as possible.)

Unbeknownst to many, more changes to 162(m) are on the horizon. Let’s dive into recent legislative events and look at the effect they will have on practical considerations such as forecasting future deductions.

Recent Legislation

In March 2021, the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) was passed and signed into law in order to alleviate the impacts of COVID-19. Although headlines at the time focused on personal and business stimulus, ARPA also affected tax rules.

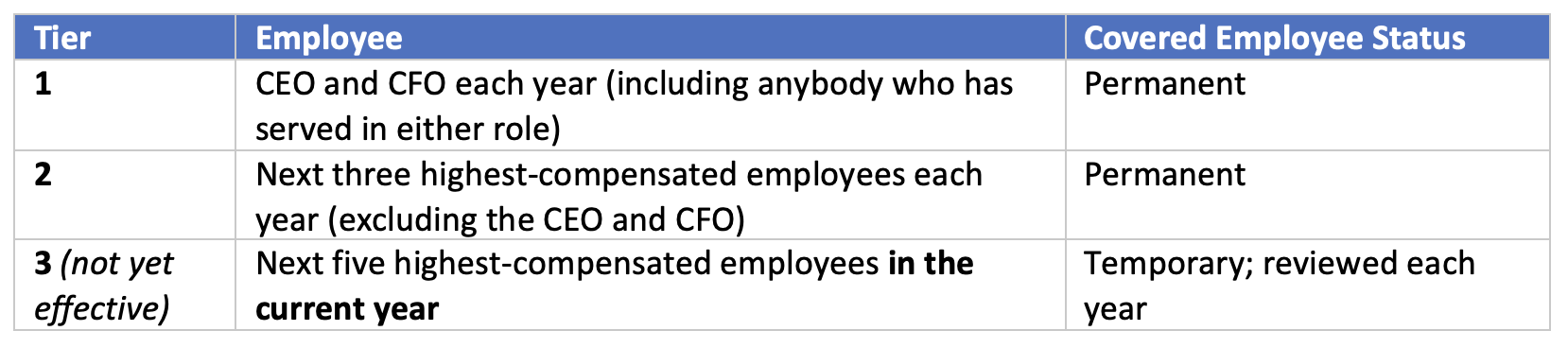

Under the ARPA, 162(m) would expand the list of covered employees to include the next five highest-compensated individuals for tax years beginning in 2027 (see Tier 3 in the table below). To help limit the number of covered employees, these next five will drop off once they are no longer in the top ten (i.e., the five original plus five additional employees).

To illustrate how this works, let’s use a sample company where the CFO is taking a lower-level position while transitioning out of the company. As a result of the transition and diminution of duties, this original CFO places eighth in a list of the highest-compensated employees. Nonetheless, they would be considered a covered employee under Tier 1 for the current tax year, not Tier 3. The new list of covered employees would include the current CEO and CFO, the original CFO, and eight additional employees as follows:

Companies must therefore track two separate groups. First is the group of permanent covered employees comprised of the CEO, CFO, and next three highest-compensated individuals in any year. The second group is the five additional employees in each specific tax year. Today’s tracking methods are effective enough for the permanent employees, especially for companies with little to no turnover at the top levels of management. But with ARPA doubling the annual covered employee list and introducing much more variability in that list, companies will likely need to revamp their tracking process to accommodate the new rules. This complexity is magnified when trying to forecast future years, which we’ll discuss later.

Naturally, the expansion of covered employees is more likely to capture atypical compensation situations in a given year, such as a major hiring event, change in control, or large one-off equity grants. We predict the current tax year-only group will be more volatile in companies with constantly evolving business operations.

One special case worth noting is business combinations. The list of covered employees for the postcombination company will consist of Tiers 1 and 2 for all precombination companies under the principle “once a covered employee, always a covered employee.” However, none of the next five highest-compensated employees from the precombination companies will be on the permanent list of the postcombination company, consistent with that being refreshed each year. We’re awaiting further authoritative guidance on what should be done in the year of acquisition itself.

Potential Changes from Upcoming Legislation

In September 2021, the House Ways and Means Committee finalized proposed adjustments to the Build Back Better (BBB) bill. The bill passed the House but remains stalled in the Senate. Nevertheless, elements of the bill are being considered for a new bill.

One of BBB’s proposed changes is to accelerate the effective date for including the next five highest-compensated individuals as covered employees. The ARPA legislation requires this to be implemented after 2026, but the BBB provision would fast-track it to 2022. Congress may not be quick to act on a new bill, but even expanding the list in 2023 or 2024 would require companies to begin the tracking process now and reduce existing deferred tax assets (DTAs) that are built up for what would be the new covered employees.

Another proposed change is to expand the definition of “applicable employee remuneration” to include commissions, post-termination compensation, and beneficiary payments. Further, compensation considered under 162(m) wouldn’t need to be paid directly by the company.

These developments, while not finalized, show that further changes to Section 162(m) may come sooner rather than later and therefore require close attention.

Forecasting Future Deductions

Today, most companies are familiar enough with the deductibility limits instituted by 162(m), but many struggle to bake them into forecasts. To be fair, tax settlement forecasting is one of the most complex topics we face. There are numerous levers to consider such as future awards being issued, the timing and amount of future exercises, and future stock prices (much less future tax rates and other assumptions).

When it comes to 162(m), we’ve seen numerous methods of incorporating Section 162(m) rules into forecasts of future tax deductions. The simplest is to flag awards to employees that could be covered employees under 162(m), whether permanently or for a single year. While simplistic, this allows for easy identification of upcoming equity settlements, consideration of salary and bonus changes, and potential retirements (which could thrust another employee into the covered list). Adding such a flag for manual review should be the bare minimum for any forecast.

Important to determine is whether to take a “salary first” or “equity first” approach. As the descriptors suggest, when determining deductibility in a given year, you would consider either (a) salary and bonus compensation first or (b) the value of exercised equity compensation first. For many large companies, salary and bonus are predictable and can exceed $1 million outright. In that case, it’s easy to apply the salary first method since all equity settlements are automatically nondeductible.

If salary and bonus are less than $1 million, or the company chooses to apply the equity first approach, time-based restricted shares are typically considered first. Stock price fluctuations affect even those settlements, but the timing and amounts are typically easier to predict than stock option exercises and performance-based awards. If the equity awards of any covered employees will be considered for tax deductions, we highly recommend running multiple scenarios that flex stock prices and other material drivers.

With an additional five employees in the mix following ARPA—and the probability that some will be covered employees for only one year—the complexity of forecasting DTA balances and excess tax benefits increases considerably. At larger companies where all ten covered employees receive over $1 million in salary and bonus compensation, there isn’t much left to be done: All future equity compensation will be nondeductible. Those with employees who approach the $1 million cap have their work cut out for them—just one settlement can mean the difference between staying under the cap and exceeding it. This means that an individual settlement event can be partially deductible. A robust forecasting process is needed to identify this and apply a pro rata tax rate accordingly.

The temporary covered employee group won’t take effect until 2027 barring any legislation that accelerates this timeline. But we’re less than one year away from that rule applying to a new award with four-year cliff vesting, so we advise making plans sooner rather than later. The addition of temporary covered employees could mean that, after only two years, your list of covered employees would triple! For more considerations on forecasting deductions for covered employees, read our article here.

Special Rules for Covered Health Insurance Providers

Even before the ARPA and the TCJA, another piece of legislation sent ripples through the tax industry: the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Under the ACA, specifically in 2013 when the final regulations took effect, subsection 162(m)(6) applies a $500,000 limit on tax deductions for every individual in a covered health insurance provider (CHIP). To qualify as a CHIP, more than 25% of an insurer’s gross premiums from health insurance must arise from “minimum essential coverage,” which the ACA defines as coverage under various government sponsored programs (like Medicare and Medicaid) or employer-sponsored plans.

This subsection is different from the standard 162(m) rules in that:

- The compensation limitation is $500,000 (not $1 million)

- All employees that provide service to the CHIP—not just the CEO, CFO, and next highest-compensated officers—must be tracked for deductibility limits

- Tax deductions are allocated based on earned year instead of paid year

The first point is relatively straightforward. The second has major implications: Companies must develop a smooth tracking process that’s dynamic and comprehensive enough to handle total compensation for potentially thousands of employees. The third difference brings the uniqueness of 162(m)(6) to bear because it requires CHIPs to track the $500,000 limit for all employees dating back to tax years beginning in 2013 (when the ACA was passed).

Allocating annual salary and bonus information to their respective earned years is as easy as filtering for payment date in payroll. However, equity awards must be tracked exercise by exercise. Each award has its own allocation period beginning on the grant date and ending on the earlier of the settlement date or termination date (irrespective of post-termination exercise windows). Previous years’ salary and bonuses are considered alongside the allocated equity values to determine how much compensation is deductible in the current year.

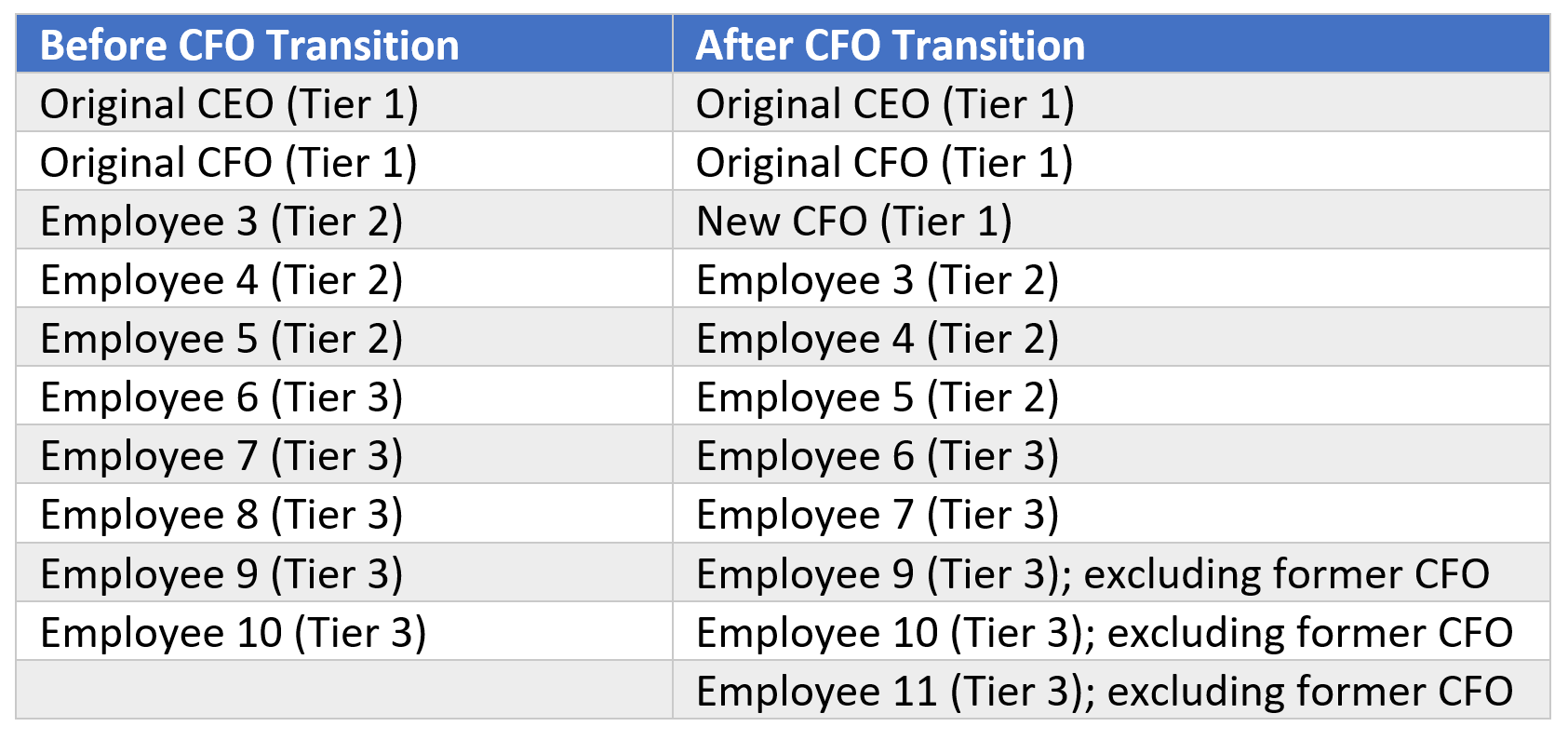

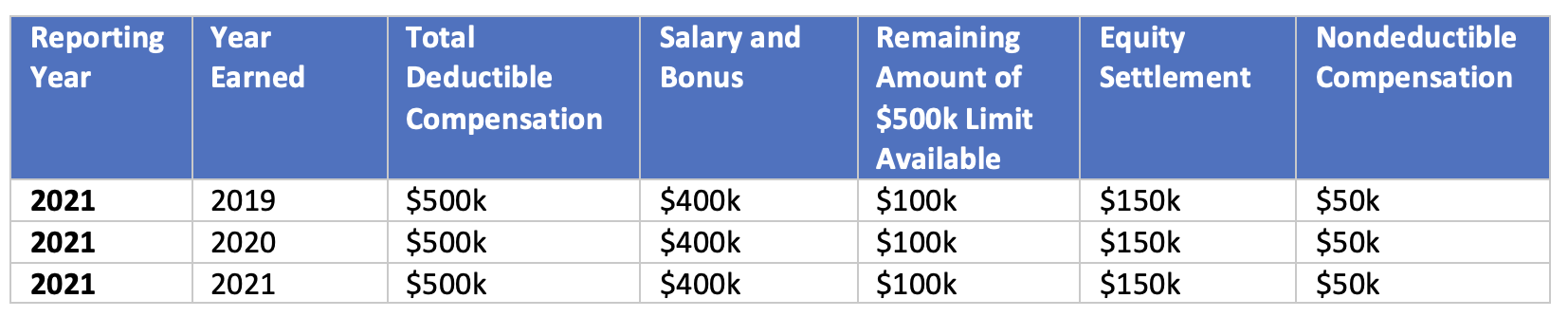

Let’s walk through an example. Mark Apple joined company HealthChip three years ago with a salary of $350,000 and annual bonus of $50,000. His cash compensation is therefore $400,000 per year, leaving him $100,000 under the deductibility limit. As part of his sign-on package, he received a one-time RSU award with three-year cliff vesting. On the award’s vest date, which is also the exercise date of the RSU, the total value Mr. Apple received was $450,000.

Let’s look at how the deductions would be calculated across these three tax years. The first year is comprised of only salary and bonus.

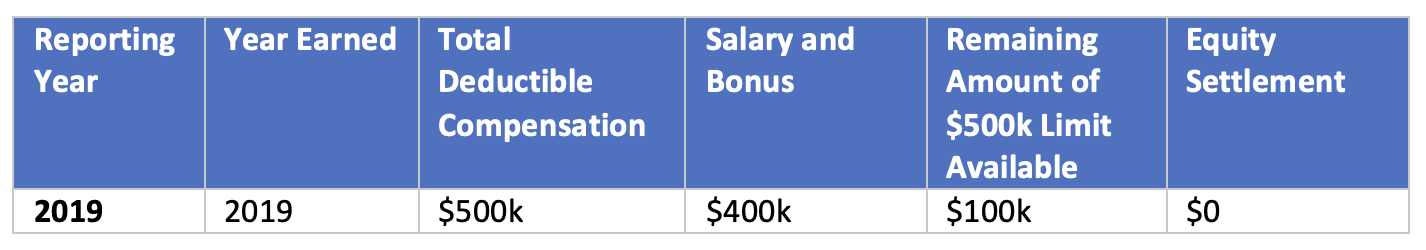

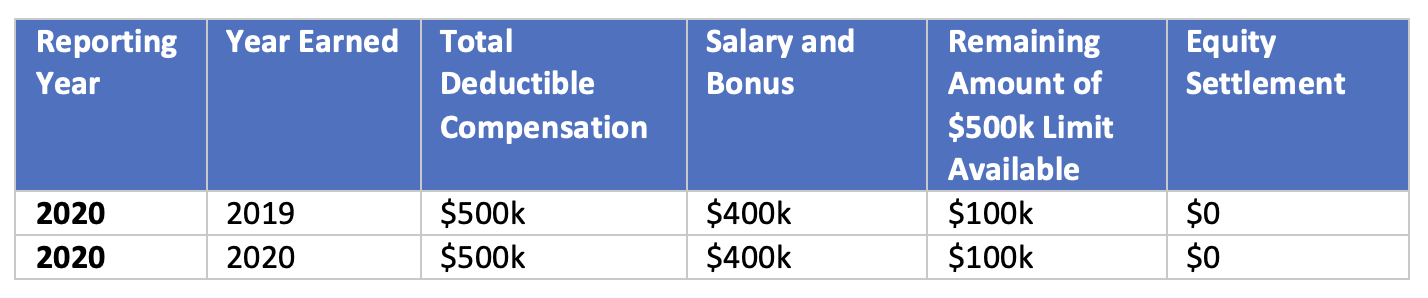

Assuming no changes in cash compensation, HealthChip will attribute $400,000 to each year’s cap of $500,000. With no equity settlements in 2020, we repeat the above calculation.

Eventually Mr. Apple hits his three-year work anniversary, triggering the release of his RSU award. Under normal 162(m) rules, the settlement value of $450,000 would be captured just in 2021, the year it’s paid. This would be true even for a covered employee since the cash compensation plus the equity settlement would combine to less than $1 million. However, for CHIPs the value is allocated based on the number of days between grant date and settlement date. For simplicity, our examples assume an even number of days over a three-year period, meaning $150,000 is attributable to each year.

However, HealthChip can deduct only $500,000 of total compensation each year. Therefore, $100,000 of equity value can be deducted for each year and $50,000 is nondeductible for each year. This total deduction of $300,000 out of the $450,000 in value delivered on the settlement date is all recorded in the current year. Thus, a total of $700,000 in cash and equity compensation is deducted in 2021 (with no amendments to prior returns).

These calculations need to be repeated with each year and with each equity settlement. Our example with Mr. Apple’s award was simple—a consistent salary and bonus, and only one award. Any prior awards that settled between 2019 and 2021 would leave even less room under the $500,000 cap. It’s crucial to have robust, dynamic processes that can handle these allocations. Spreadsheets may hold up in the first few years but wear thin over time.

Wrap-Up

From CEO pay ratio to realized pay disclosures to pay equity, the public wants additional visibility into compensation practices and accountability for unfair pay practices. One way to avoid excessive pay is to limit how much value the company can deduct. And the trend with 162(m) is to cover more employees and allow less compensation to be deductible. Now is the time to refine processes around tracking employees and awards, applying the necessary 162(m) limitations and and accurately forecasting future years along the way.

We’ll continue to monitor news coming out of Congress and the IRS. As always, we’re here to help with any questions on Section 162(m) or other compensation topics.