RE-views and RE-visions: Evaluating Changes to Your Retirement Eligibility (RE) Provisions

Introduction

Amid a highly competitive talent marketplace, more and more companies are revisiting the terms and conditions of their compensation and benefit plans to see whether they need any changes. Retirement eligibility, or RE, is a key part of this assessment.

RE refers to qualification for favorable treatment upon voluntary termination. Typically, this involves meeting thresholds for age and/or time of service to the company. With respect to equity compensation and long-term incentive plans in particular, RE means favorable equity treatment such as acceleration or continued vesting rather than forfeiture. For example, a common RE provision would be something like: If you’re at least 55 years old and have worked with the company for 10-plus years, you’re entitled to all of your unvested equity when you retire.

We’re seeing a general trend toward more generous RE provisions in stock compensation plans (i.e., greater benefit and/or more easily attainable eligibility criteria), but we’re also seeing some companies go in the opposite direction. In any event, the main goal is to ensure any retirement provisions are thoughtful, align with the company’s goals, and represent the best use of resources.

In this article, we’ll focus on three critical decision points to expect as you review the RE provisions of your equity plans:

- Should you offer retirement eligibility at all?

- How should the retirement eligibility criteria be set?

- What vesting benefits should we provide for retirement eligible employees?

Each of these decision points can have implications for the company’s human capital strategy, alignment with market practices, and financial reporting.

Decision Point 1: Should you offer retirement eligibility at all?

RE is a benefit, just like health insurance or 401(k) matching. While RE is typically less important to candidates than basics like competitive salary, favorable equity vesting for those who retire from your company can still tip the scales in attracting prospective employees, especially those who are mid-career or later.

RE can also motivate employees to continue working until they qualify for the benefit. As an example, if a significant portion of employees are 40 to 50 years old, and you offer RE at age 55, that provision may encourage people to stick around longer than they would have otherwise. Requiring a certain level of tenure to achieve RE can likewise boost retention and help extend the average tenure.

To support both talent attraction and retention goals, we encourage companies to think through a few different key considerations when assessing whether it makes sense to offer RE.

Stability and Continuity

Corporate policies, RE included, tend to be stable over time—and for good reason. Major changes are time-consuming and require buy-in and collaboration across different functions. HR and compensation teams need to align on the design, legal needs to draft or amend employment and award agreements, and finance and accounting need to manage the accounting and budget implications.

Then there’s the work in managing the people side of change. A change to employee benefits can be met with skepticism, especially if employees think it leaves them worse off (like making it harder to become eligible for retirement). Employees need careful communication and education to address their concerns.[1] Even positive, employee-friendly changes require effective communication so employees understand the updates and their value well enough to drive the desired impact.

Strategy

Since RE provisions are supposed to help with recruitment and retention, companies should periodically assess the role RE can play in accomplishing those goals.

If no RE provisions are in place, see if the data reveals termination patterns that you might expect RE to mitigate. Is there a meaningful chunk of employees at an age where retirement considerations are in play? And does there seem to be any spike in termination activity in advance of a potential RE threshold?

Suppose your employee population has a substantial number who are 40 or older. If you see an uptick in terminations around age 50, adding RE at age 55 or 60 may prompt people to stay with the company longer. On the other hand, if you see an unexpectedly low number of terminations around age 50, it may be worth exploring if added benefits would help employees reach retirement goals.

If RE is already in place, see if termination activity goes up once people hit the RE threshold. If so, that would suggest that the current provisions are working as designed, and some employees are delaying retirement until they qualify for incentives. In some cases, it’s even possible for the RE incentive to be too strong, creating a cliff of high turnover in certain roles.

If there’s no increase in retirement around the RE threshold, it could make sense to find out why. There may simply be no employees at or near retirement age. Or, people are leaving before they become eligible, potentially suggesting that employees don’t view the RE provisions as valuable enough to delay retirement. Still another possibility is that people are working beyond the RE threshold, suggesting that RE provisions aren’t factoring into their decision to stick around.

Either way, find out if the companies that are competing with you for talent are offering RE provisions. The answer could help you decide how far you need to go in using RE to attract and retain talent.

Peer and Market Prevalence

We estimate that a small majority of companies currently offer at least some favorable equity treatment in retirement. However, the trend is stronger in certain sectors and industries. As with anything compensation-related, there’s a natural tendency toward clustering. Companies that compete for talent will attempt to keep up with the market.

In our experience, industries that skew younger in their equity-eligible populations (e.g., technology) are less likely to offer RE than industries that skew older (e.g., retail or finance).

A good way to check into peer practice is via public SEC filings, which will include stock plan documents and award agreements. While much of the information in those filings relates to top executives, RE treatment is commonly aligned for executives and non-executives, so it’s often reasonable to extrapolate in this area.

Reporting Impact

To know whether a change to your RE provisions are financially feasible, we recommend modeling the expense impact that an added or amended RE provision will have. This is a critical step to avoid unexpected financial statement impacts.

The accounting guidance in ASC 718 says that if the legal vesting date is non-substantive, the requisite service period should end whenever the employee can terminate and still vest in their award. This means that when an employee is entitled to any portion of unvested shares due to the RE provision, the impact for those shares needs to be considered in the expense accrual. Put simply, if RE provisions mean that employees become entitled to awards sooner—whether via acceleration or continued vesting—the expense will be accelerated to be recognized over the shorter period ending on the RE date.

The results of this analysis will probably be intuitive. If you increase your RE benefit, you’ll likely see expense go up over the first few years of adoption due to amortizing more expense over a shorter time. Assuming the retirement benefit doesn’t change overall grant value practices, this acceleration of expense will be offset in future years and the expense run-rate should revert to a more predictable level.

One finding that sometimes surprises companies doing this analysis is that the long-run expense levels slightly increase due to fewer forfeitures occurring in the future. If shares are earned earlier due to new RE provisions, it results in fewer expected forfeitures in a long-run forecast and elevates the expense run rate slightly.

Decision Point 2: How should the retirement eligibility criteria be set?

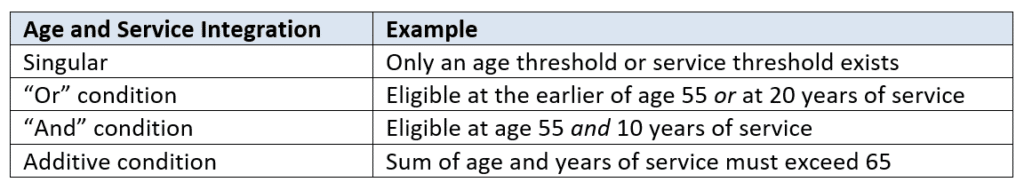

All companies use age and/or years of service to define when someone becomes retirement eligible. But they differ on where to set those breakpoints (what age and how many years of service?) and how to integrate them with each other. Typically, companies choose one of the following:

Strategy

Setting RE criteria relies on many of the same considerations as deciding whether to offer RE.

First, the threshold should generally be higher than the age/tenure of people who have historically left the company around that point in their career (due to retirement or otherwise). Otherwise, they won’t have an incentive to stay.[2]

Second, the threshold should be near enough to relevant employees that it’s a realistic incentive. Offering RE at age 65 when people are departing at 50 is unlikely to have the desired effect.

Third, the RE criteria need to protect company interests. If you don’t want people retiring only to go work for a competitor, it helps to avoid overly lenient RE criteria (a 50-year-old is more likely than a 65-year-old to work again). Non-compete provisions tied to receiving the special treatment can help as well, jurisdiction permitting.

By the same token, if you don’t want people leaving immediately after a grant is made, you can require some amount of service after a grant (often one year) in order to realize the favorable RE treatment for that grant. In addition, or instead, you can require a notice period to qualify for retirement treatment. While a notice period can help with retirement planning, there are potentially complicated implications for expense recognition that should be discussed with internal and external advisors.

Important to acknowledge is that these criteria above can be in tension. One creative solution in the market is having tiered eligibility criteria with increasingly favorable equity accelerations. As an example, a company might offer partial acceleration at age 55 and then full acceleration at age 62.

Prevalence

Before establishing or amending RE, we recommend studying your company’s data and peers, especially since there are too many combinations of age and tenure to lay out all possible RE criteria.

In our experience, the most common threshold is 55 and 10—that is, employees must be 55 or older and have 10-plus years of service. There are many variations on this, but an “and” condition is the most common. Other common approaches include an additive approach where age and tenure must exceed 65, or hybrid approaches where someone must reach either age 65 or age 55 with 10 years of service.

Less common approaches include a service requirement only (e.g., 20 years of service), or an age or a service requirement alone (e.g., earlier of age 60 or 20 years of service). In both cases, companies run the risk of edge cases like someone retiring mid-career at age 40, which isn’t necessarily the spirit of the program.

Decision Point 3: What vesting benefits should we provide for retirement-eligible employees?

After defining the RE criteria, it’s time to decide how to handle awards upon a qualifying termination.

The first key question to answer here is whether to offer full or partial acceleration. (The latter is usually prorated based on length of service.) In cases where the baseline vesting for an award is already prorated—for example, some kind of graded vesting—full acceleration is typically offered. Otherwise, the RE provision wouldn’t provide much (if any) benefit. For cliff-vesting time-based awards and almost all PSU designs, both full and partial acceleration are common.

Next, consider whether to pay out awards at retirement (true acceleration) or on the original vest schedule (continued vesting). The RE awards would be earned either way, and become non-forfeitable upon achieving eligibility. However, there’s the additional question of when shares are actually released to a retiree. Releasing shares immediately upon retirement is beneficial since it pays out employees and gives them the flexibility to use the awards’ value as they see fit. Conversely, adhering to the original vest schedule may help with individual tax planning.

For time-vested awards, both accelerated and continued vesting are common. For performance share units, continued vesting is the norm. The reason is that the payout typically occurs at actual performance, and that performance isn’t known until the end of the performance period. Thus, continued vesting (not accelerated) is required in order to know the payout amount.[3]

For stock options, the question is how long to allow exercise upon retirement (the post-termination exercise period, or PTEP). Most companies’ provisions have a short PTEP—often 90 days—for ordinary, non-retirement terminations. Terms tend to be more generous for retirement, though.[4] Often, it’s the full remaining contractual life of the option. In-between solutions are also possible, such as offering multiple years but not the full remaining term.

Reporting Impact

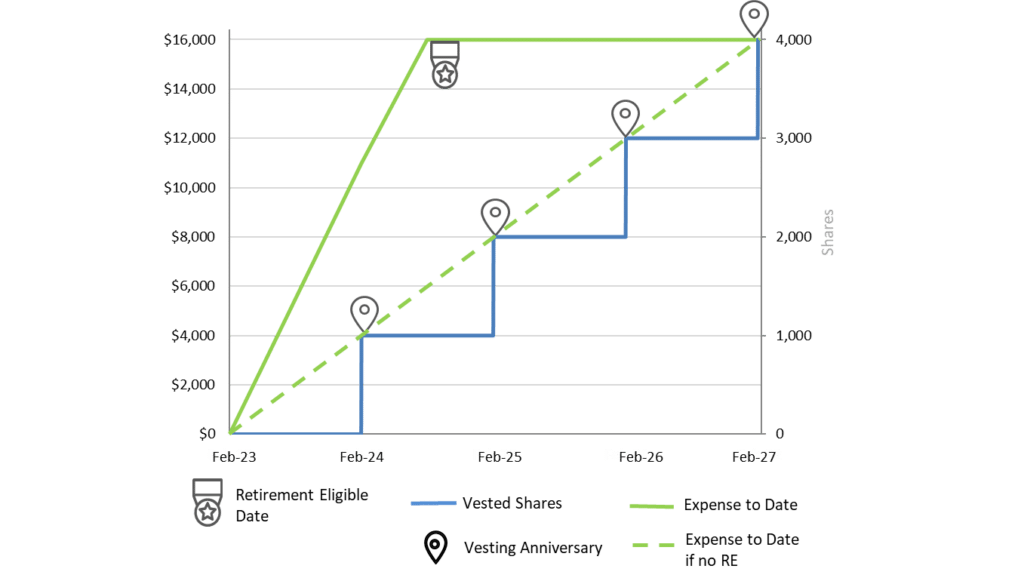

The vesting benefit given to RE employees has a major impact on financial reporting. As we mentioned earlier, expense amortization should align with the timing of when shares are earned. If retirement-eligible employees are entitled to full vesting of unvested equity, then all expense should be accrued as of the RE date. The chart below shows an employee reaching the RE date during the vesting period. In this case, the full award value is amortized between the grant date in February 20X3 and the RE date in August 20X4, instead of over the four-year legal vesting period.

This principle of accelerating expense to align with the timing of when shares are earned applies regardless of the RE benefit that is provided (accelerated vs. continued vesting).

This can become more nuanced for partial or prorated RE provisions. If an employee is entitled to a portion of shares, then a portion of expense might need to be accelerated, while the unearned portion of shares continues to expense over the vesting period. If employees are entitled to a prorated payout of shares at retirement based on the number of months they have earned the award, then the amortization pattern can generally accrue in line with the legal vesting schedule, since at any given point the total expense will align with the number of shares that have been earned by the employee—it’s the same straight-line pattern.

Beyond the expense impact, it’s worth noting there’s a diluted earnings per share (EPS) impact of RE provisions. ASC 260-10-45-13 states that once shares are no longer contingently issuable, they should be added to common shares outstanding for purposes of calculating basic EPS. Keep in mind that options and performance awards will still have contingencies after RE is reached, given performance or stock price achievement would still be necessary for the shares to be delivered to the employee. We have much more information about the EPS considerations here.

Finally, while income tax is delayed until delivery of shares, FICA taxes are due upon RE for restricted stock units, as the units are no longer at risk of forfeiture. We discuss this in more detail here.

Wrap-Up

Thoughtfully designed RE provisions can be an important tool in the employee benefits toolbox. Even so, it’s important to keep a pulse on external trends (changes in market or industry practice) and internal trends (termination and retirement patterns) to assess the effectiveness of your RE provisions or whether implementing new RE provisions may make sense. On top of monitoring the relevant data, you’ll also need to model the impact of any prospective changes in terms of how they’ll impact budgeting, expense, and other disclosures to avoid potential surprises.

We hope this discussion is helpful to your internal conversations. If we can be of any assistance or if you’d like to discuss this or any related topics, please contact us.

****************************************************

[1] It can also help to apply less favorable changes prospectively (say, by grandfathering existing employees or awards into the older, more favorable terms).

[2] Sometimes, our clients are trying to solve the opposite problem: They would like to reduce their workforce but without the major disruption of a layoff. If they have the appropriate workforce age demographics, they can increase voluntary turnover by making RE more generous or available earlier.

[3] Occasionally, we see performance share units eligible for accelerated vesting upon retirement at target (in order to avoid needing to wait to know the amount). However, this can create messy incentives where someone can retire in an underperforming year in order to obtain a higher payout.

[4] A PTEP longer than 90 days would disqualify an incentive stock option (ISO), so care should be taken if ISOs are granted and the RE provisions apply.