The New State of Play in SPACs: Forgotten, but Not Gone

Whatever happened to special purpose acquisition companies, or SPACs? Only a few years ago, celebrities—and celebrity investors—were seemingly clambering over one other to get in on the SPAC craze. Did the 15 minutes of fame for this type of entity come and go?

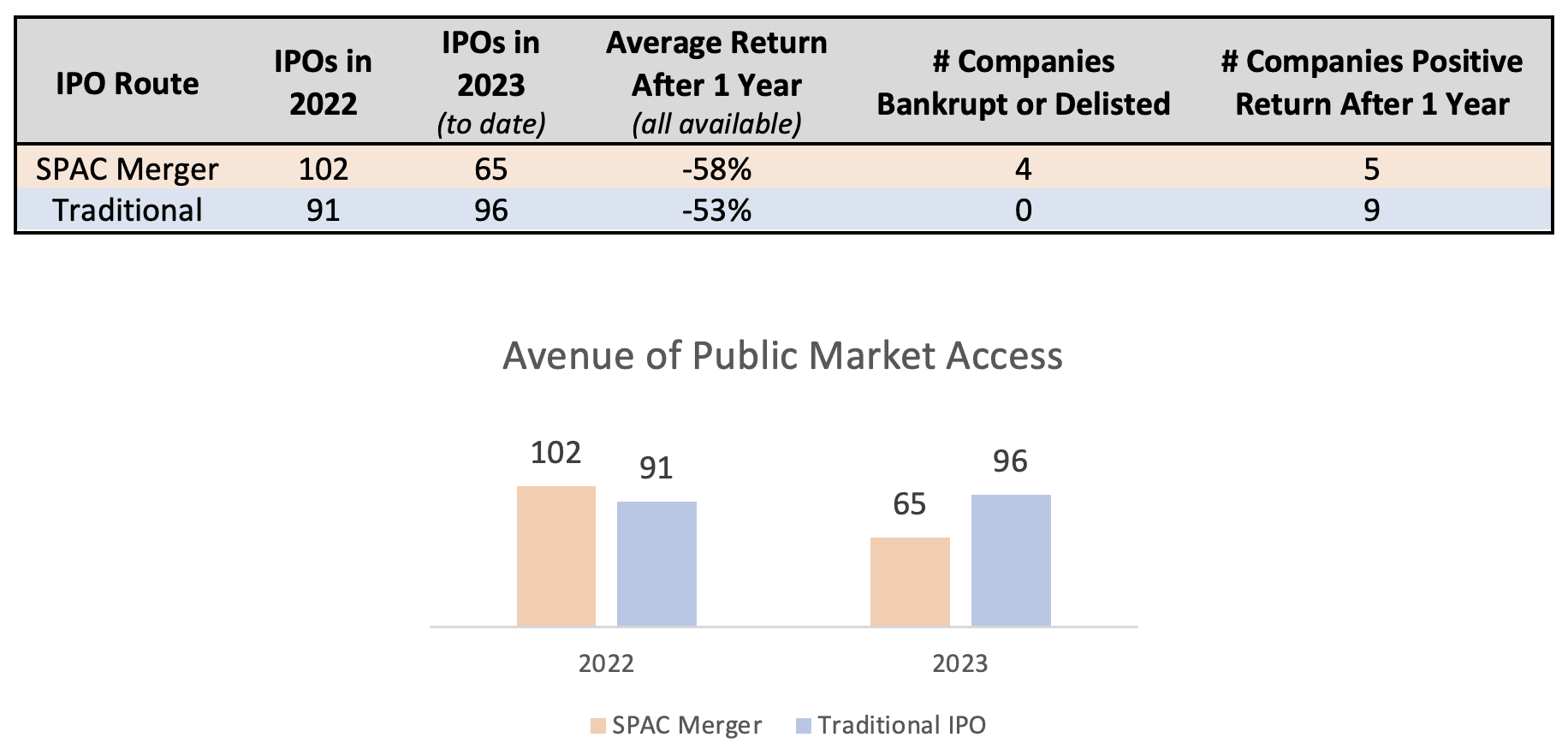

Not exactly. Since the beginning of 2022,1 167 companies have been listed via SPAC merger versus 187 companies going the traditional route. In 2023 so far, those numbers are 96 and 65 respectively. There has been some drop-off, but nothing drastic. So why aren’t SPACs dominating headlines in the business media like they used to?

Early SPAC Success

Successful SPAC mergers have been around for a long time. Examples include DraftKings (52% return from IPO),2 Fisker (58% in the year following the IPO), Opendoor, and even Burger King (in 2012!). In fact, SPACs have been used since the 1980s as a way for companies to avoid the hassle of an IPO.

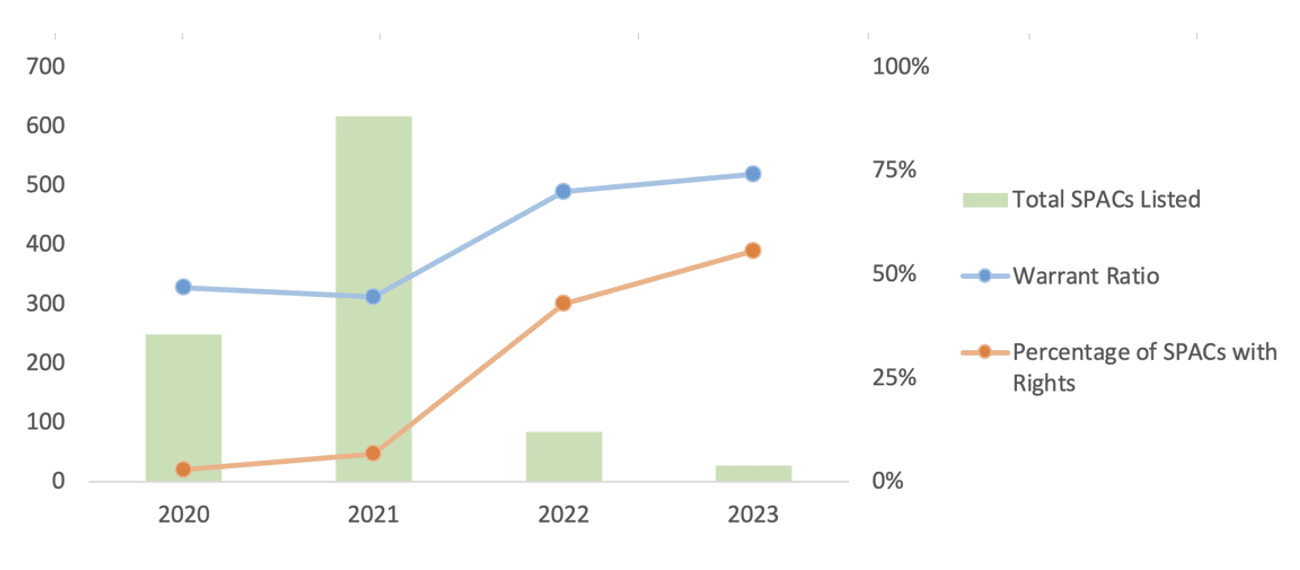

The positive returns for many SPAC mergers, combined with a smaller number of total SPACs in the market in 2020, helped fuel the boom we saw in 2021.

Market Saturation

At the same time, it became harder to find target companies to take public. Target companies need a successful business and a desire to enter the public markets. They also need to be in a position where a SPAC would be an attractive alternative to an IPO. The number of companies that fit this target profile was static, while the number of SPACs was growing.

This increased the risk of failure because SPACs have only a limited time (usually two years) to find a company to take public. If that doesn’t happen, the SPAC and the remainder of its assets are liquidated and returned to the initial investors.

For SPACs that were able to find a target company and go public, it became increasingly challenging to replicate the success of earlier SPACs. The average company that went public via a SPAC merger in 2022 saw a 58% loss one year later. Four of those companies are no longer trading or public. Only five have had a positive one-year return. It’s hard to tell whether the lack of success was due to macroeconomic conditions and the broader market or the poorer quality of target companies.

SPACs versus Traditional IPOs

Are traditional IPOs better, then? To find out, we compared SPAC mergers with firms who went public through traditional IPO. Using the same metrics and calculations as before, the average company that went public via traditional IPO in 2022 saw a 53% loss one year later. These companies are still public as of September 30, with only nine having a positive one-year return (Figure 1).

It seems that success in going public is now harder to come by, regardless of the avenue of IPO. The challenge is slightly greater for companies that merge via a SPAC, given the slightly lower returns and higher probability of delisting or going bankrupt (relatively) soon after their public debut. Some of this difference could be due to smaller, younger, and riskier firms taking advantage of SPAC mergers to tap the public markets since SPACs have lower listing requirements.

Enticing Investors

To attract investors for the SPAC, companies issue units at IPO that typically consist of a common share and a fraction of a warrant. These warrants let the holder purchase the underlying common share at a fixed price anytime within five years after the de-SPAC merger. Some SPACs also include a fraction of a right in the unit too. A full right converts to a common share at the de-SPAC merger.

With the increase in the number of created SPACs and therefore more competition to attract investors, we’d naturally expect these newer SPACs to try to sweeten the deal by including rights or increasing the fraction of either security (Figure 2).

Sure enough, both the warrant ratio (fraction of a warrant per share of stock within a unit) and share of SPACs also including rights have increased in the couple of years following the SPAC boom.

SPAC warrants are trading at all-time lows on the public markets. In other words, investors don’t see much value in SPAC warrants, at least compared to prior years. This also helps explain why we’re seeing higher warrant fractions or additional securities included in the units offered to investors.

A SPAC IPO and issuance may include other, less common, features and options to entice investors. For more information, check out our article on the valuation of these features.

What’s Next?

SPACs may seem to have disappeared, but the data suggests otherwise. That said, traditional items issued with SPACs, like warrants or rights, are at historic lows. The implication is that it’s harder than before to find a solid company to take public and create sustained success (and some don’t ever find a company). The lower probability of success and finding a company are priced into the market. As the market becomes less saturated, we expect it will reach a steady state in which the SPAC merger is a viable route for going public, much like the traditional IPO is now.