The Proxy Is Coming! What Finance Leaders Need to Know About Current SEC Rule-Making

“The proxy is coming, the proxy is coming!” This adaptation of Paul Revere’s famous cry was the theme of a panel discussion at this year’s Financial Executives International (FEI) Corporate Financial Reporting Insights Conference.

The traditional model has been that Finance owns the 10-K and everything subject to generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), while Legal and HR own the proxy. The two worlds would rarely meet other than in exceptional situations like defending against an activist campaign.

That tradition is unraveling. The proxy is one area where collaboration among departments will be critical moving forward. The most successful corporate teams will boast deeply integrated and cohesive partnerships across Finance, HR, and Legal.

I’m grateful to my fellow panel members for a lively and informative discussion. Jonathan Gregory, corporate controller at Hershey, moderated and gave terrific practitioner commentary. Rob Jackson, former SEC commissioner and current professor at New York University School of Law, provided broad insight that reflected his time at the SEC and his experience in banking and the legal profession. And our friend Steve Soter, executive advisor at SEC Pro Group, played a key role in framing our conversation even though he was in transit to the UN Climate Conference.

In this recap of the discussion, I’ll cover several emerging issues with the proxy, how it’s used, and why cross-functional collaboration is essential to getting it right.

The Investor Landscape Is Evolving

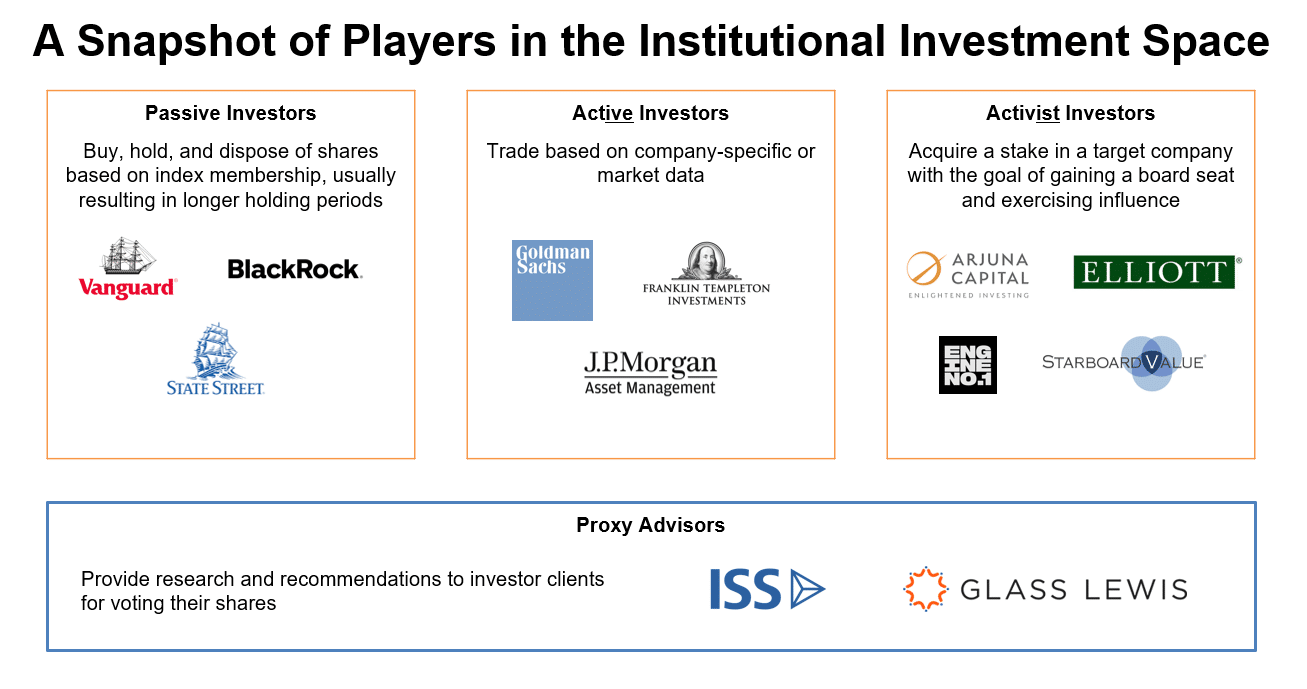

If every investor were an active investor, perhaps the proxy would be less relevant. However, over the last 20 years, passive institutional investors have overtaken their active counterparts.[1] Funds sponsored by companies like Vanguard, State Street, and BlackRock buy defined sets of index stock and have charters requiring them to hold those constituent stocks for however long they remain in the index. For this reason, they’re often referred to as forever investors.

Because the accounting results in the 10-Q or 10-K are rarely actionable for passive investors, governance effectiveness and long-term systemic risks—which are primarily reported (and voted on) in the proxy—become the focus.[2] This means the proxy is vital to at least half of the average company’s investor base.

As such, institutional investors have built large stewardship teams to review proxy proposals and related disclosures. Whereas the active investor hands out rewards and punishments through buying and selling a stock, the passive investor does so through say-on-pay votes and director elections.

At the same time, active investors, as a group, are more diverse than you might think. Some are computer algorithms that automatically trade using pricing data, whereas others are seasoned human analysts who study the substance of reported financial data.

All investors are required to exercise stewardship and discipline in how they vote proxies. While investors must not blindly outsource their voting to a proxy advisory firm, as a practical matter they may substantially rely on one’s voting recommendations.

Activist investors are major consumers of the proxy, with some orienting their value creation thesis around proxy-related matters. Former SEC Commissioner Jackson noted that research by Robert Bishop has found that a failed say-on-pay vote is the prime indicator to activists of an opportunity to gain support around their value creation thesis.[3] This is because it’s quite possibly the only public indicator (other than the stock price) that the broader shareholder base may be unhappy. Activists need to galvanize support for their campaign among other shareholders because their ownership will rarely exceed 10%-11%, if that.

The Proxy’s Growing Reach

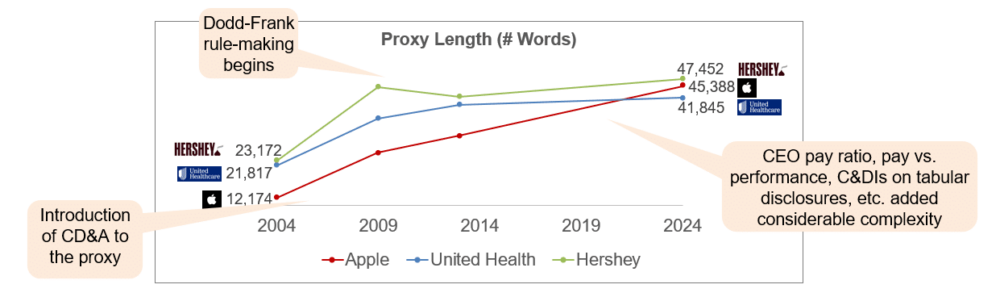

The proxy statement has grown substantially. This can be seen in both the word count and complexity of the content.

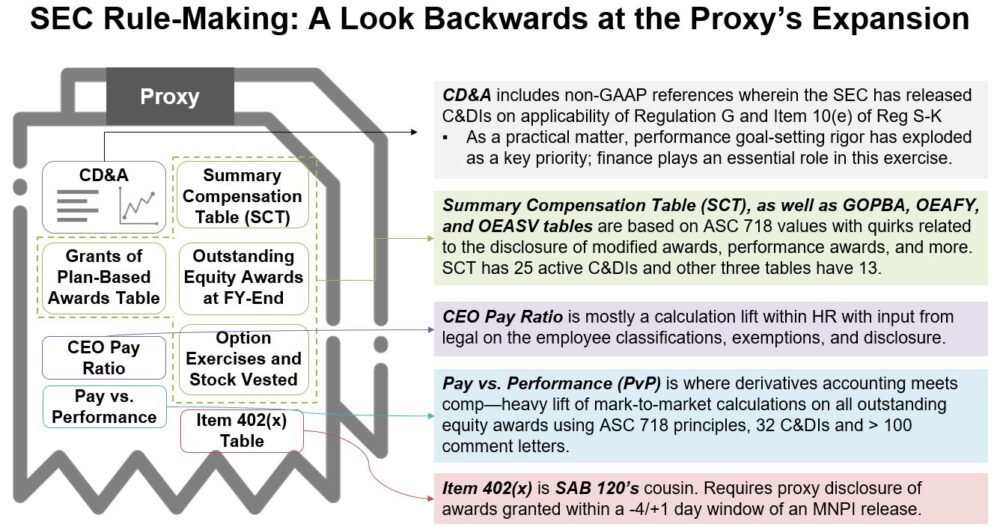

By way of a quick replay, the SEC released new proxy rules in 2006 introducing the compensation discussion and analysis (CD&A) section, as well as expanding the scope of tabular disclosure. The CD&A’s purpose is to help users understand how the compensation committee arrived at its pay decisions. This caused complexity to increase significantly, but concurrently, best practices began emerging around plain English wording and effective graphical representation.

In 2010, Congress passed the Dodd-Frank Act, which (among other things) led to new executive compensation disclosures. The first fruits for proxy purposes were the say-on-pay and say-on-frequency votes, which led to additional density.

An interesting push-pull dynamic emerged in which investors and proxy advisors became more interested in this content. They began pulling more and different analyses from companies. One manifestation was a pull for more discussion on the link between pay and performance in the proxy.

Since performance is usually expressed in non-GAAP terms, this prompted the SEC to release compliance and disclosure interpretations (C&DIs), pushing for more specific handling of non-GAAP references.

SEC rule-making continued throughout this period. By the 2018 proxy season, CEO pay ratio disclosures were on the scene. A flurry of activity has followed, including Rule 10b5-1 changes, the formal pay vs. performance (PvP) disclosure (Item 402(v)), clawback rules (Item 402(w)), as well as grant policies and spring-loading (Item 402(x)).

When you step back and look at the modern proxy, it resembles a financial statement informed by an accounting standard. There are numerous disclosures, many of which are quantitative in nature. Most are based on the formal accounting rule, ASC 718. This has come about partially in response to the SEC having released over 50 C&DIs and numerous comment letters.

Although the proxy isn’t an audited document, it’s clearly under the microscope at the SEC. What used to be a much more fluffy “storytelling” document has transformed into a technical document where the story and the numbers must align.

Enter the Plaintiff’s Bar

A broadening class of investors care about the information in the proxy and view it as central to their investment charter. This paves the way for the plaintiff’s bar to take an interest.

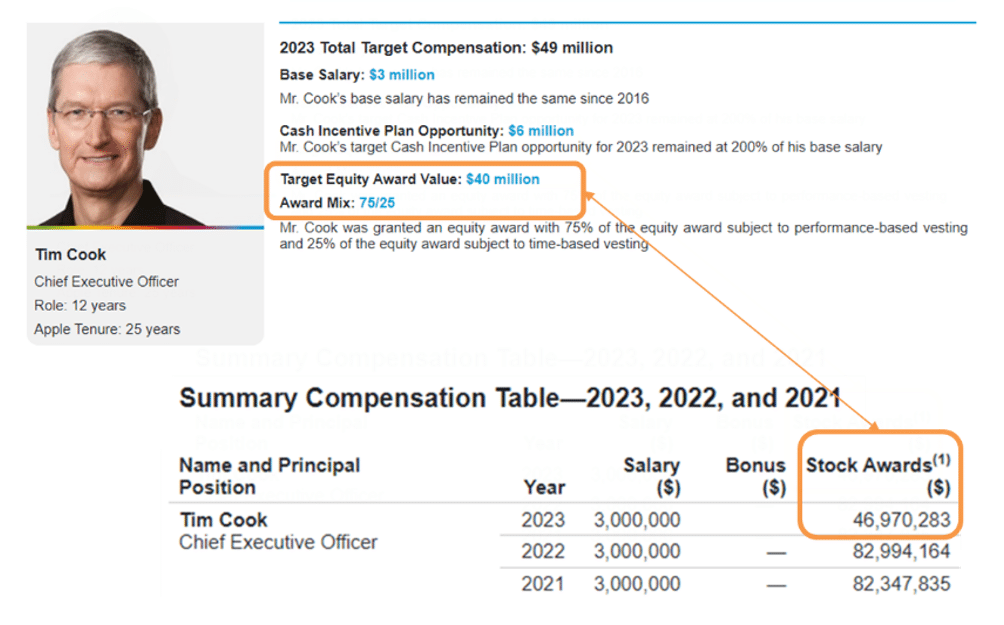

In one interesting case, the plaintiff, IBT Management Pension Fund, alleged that Apple misled investors by describing Tim Cook’s target equity grant as $40 million while disclosing the value of said grant at $46 million in the summary compensation table (SCT).

Because the SCT is based on accounting values (ASC 718), the $46 million reflects the use of Monte Carlo simulation and fair value modeling. The description of the grant in the CD&A, including how the compensation committee endeavors to size the number of PSUs granted, isn’t bound by any particular framework. There’s no rule requiring a link between the CD&A and the SCT or other tabular disclosures. In short, the compensation committee can size the grant however it wants, and there’s no obligation to tie the official accounting value in the SCT to the sizing methodology.

The danger here is using language that implies a connection between how shares are set and how the award is valued in the tabular disclosures. Practically speaking, this could stem from an innocent drafting oversight rather than an intent to mislead. This is why the finance team plays such a key role in the proxy preparation process. Not only do these professionals know the necessary terms of art, but finance leaders are trained in using precise language to tell the story behind the numbers.

Apple prevailed in this lawsuit because it used the right language in the right places, and was on the right side of the debate. However, the outcome could have flipped had a few sentences been drafted differently.

We expect to see more litigation of this nature. The sheer volume of numerical information in the proxy makes it a target. We even know of a few law firms that are running proxies through AI to look for inconsistencies that can be weaponized.

Proxy Quality and Accuracy

The financial statements are complicated for many reasons. They aggregate thousands to millions of records, traverse a broad spectrum of topic areas, and have sprawling rules governing their composition. There are also safeguards like the external audit process and materiality thresholds.

The proxy is simply different. Far fewer records go into it, and each one can be highly material. There’s also no formal external audit.

Quality needs to be a foundational theme as the proxy has become more quantitative and relied upon as a basis for decision-making. Most internal audit teams will spend time on the proxy, which is good but only attacks a limited slice of the risk. When companies outsource the preparation and calculation of all the tables in the proxy, the external provider plays a connective role across Finance, HR, and Legal. This involves applying finance principles (where and as required), distilling the compensation story that needs to be told, and following the sprawling scope of Regulation S-K rules and corresponding C&DIs.

Because the quantitative proxy is a relatively recent development, organizations may underestimate the need for traditional controls, especially given that obtaining the necessary information requires coordination among a variety of internal stakeholders. This complexity increases the potential points of failure throughout the proxy preparation process.

It’s critical to ensure that any end processes take into account how the various functions come to the table and interact with outside providers. Automation can also be an effective way to reduce mistakes. We expect changes in the proxy to be ongoing, and as it is increasingly relied upon, both the risk and costs of failure will increase.

Where Is the Proxy Headed?

Taking place only a week after the presidential election, our panel couldn’t have occurred at a more interesting time!

Post-election, the SEC’s climate rule will probably not be resurrected. The current SEC stayed the rule to give the courts time to sort out the various legal objections. However, a Republican-led SEC is unlikely to resume enforcement of the rule even if the judicial review process finds in the rule’s favor.

Former SEC Commissioner Jackson noted that the SEC’s cybersecurity disclosure rule was unlikely to be rolled back. Even though aspects of the rule were controversial, in general, it carries broad bipartisan support and is particularly important to virtually all investor classes.

I took the opportunity to discuss the regulation of proxy advisors. This issue has a storied past, but it was the Clayton SEC that prioritized drafting rules that classified proxy advisors as engaging in the act of proxy solicitation and being subject to the proxy solicitation rules in the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. Not only did ISS initiate litigation against the SEC, claiming it had overstepped its authority, but the Gensler SEC moved to relax the new rules by dropping key components.

The new SEC will likely reboot the rules adopted by the Gensler SEC or a similar version. This would reinstate the notice-and-awareness provisions, giving companies the ability to receive proxy advisor reports and publish rebuttals that proxy advisors are obligated to share with all of their subscription clients. There’s even a famous letter of this sort from Abbott.

Proxy advisor regulation would give registrants a louder megaphone to tell their story and directly rebut perceived logical flaws in a proxy advisor report. While this may not be a good use of time for most companies, a tight collaboration across Finance, HR, and Legal will be essential when appropriate.

We also discussed another major focus area for the SEC, insider opportunism. This was the motivation behind revisions to the 10b5-1 rule as well as Staff Accounting Bulletin (SAB) 120, published in 2020. The SEC’s 10b5-1 revisions gave rise to an Item 402(x) disclosure in the proxy related to “spring-loaded” or “bullet-dodging” equity grants. Unlike its SAB 120 counterpart, Item 402(x) is full of bright-line standards: It only applies to proxy NEOs, options, and option-like awards. It has a hard cutoff date for awards granted four (or fewer) days prior to the release of Material Non-Public Information (MNPI) and one day or less after the release of MNPI.

It’s important to understand that a lack of collaboration among Finance, Legal, and HR is bound to miss the intersection of Item 402(x) and SAB 120. I’ve personally witnessed many conversations where one party said the coast was clear on making a grant but was only taking into consideration the 402(x) framework and not how that very action would trigger an SAB 120 issue.

Beyond the SEC: Other Investor Dynamics

The growth of the proxy has also been influenced by a trend among investors to seek a wider range of information independent of SEC rule-making. Of particular interest are how performance goal-setting rigor is demonstrated and communicated, shareholder dilution linked to excess granting, and broadening compensation committee charters.

The performance goal-setting question comes in the wake of investors (and even boards) pressure-testing whether above-target payouts are truly a function of “good” performance as opposed to softball goals. While this is a highly nuanced topic, the best practice is for the finance function to use existing strategy models to prove why the threshold and stretch goals are what they are in relation to target. The target goal is generally the most supportable because it roughly aligns with external guidance to the street.

Dilution management has hit center stage as many companies in human capital-intensive industries have steadily upped their grant levels. The doomsday scenario is committing to higher grant levels only to witness declines in the stock price that mechanically trigger a surge in dilution. However, dilution management is challenging to get right because different external constituencies measure it differently. The best practice is to maintain multiple measures and benchmarks, in addition to scenario modeling how sensitive dilution is to changes in the stock price.

And, of course, just as many companies run the risk of over-granting and triggering dilution that creates a deadweight on the stock price, other companies run the more insidious risk of under-granting.

Finally, there’s been an organic push among many institutional investors for board compensation committees to broaden their charters to encompass human capital management as a whole—instead of only the compensation of the CEO and their direct reports. While this trend has good reasons behind it, such as the reality that culture and employee engagement are cornerstones to long-term business model sustainability, the devil is in the details. A broadening compensation committee charter will require committees to engage with much more information and ask entirely new categories of questions.

Closing Thoughts

The proxy now carries more weight with investors, who use it extensively. This is mainly a reflection of the growth in passive investing. But even active investors (who buy and sell the stock) and activist investors (who accumulate holdings to acquire board seats or otherwise produce change) rely on the proxy as a key information source.

At the same time, the proxy has gotten more complicated, both because of its interdependency with ASC 718 accounting rules and because investors demand more transparency and detail on executive compensation, dilution, and other governance topics. As the bar for informing investors has risen, companies have increasingly prioritized analytics, forecasting, cross-functional collaboration, and automation (to reduce risk and drive efficiency).

We help companies with all facets of their proxy preparation, so we’re familiar with the proxy’s technical, strategic, and framing challenges. One of the key lessons from our experience is that close collaboration among HR, Finance, and Legal is required to tackle these challenges effectively. Now is the time to get your processes aligned and improve the connectivity between these crucial teams.

[1] Research by Morningstar, Active vs. Passive Funds by Investment Category, March 21, 2024.

[2] The proxy is not the only forum through which governance and systemic matters are reported. The SEC’s new cybersecurity rule is reportable in a Form 8-K, in addition to Forms 10-K and 10-Q. The SEC’s climate rule would have required 10-K reporting, though some companies voluntarily provide climate-related disclosures in their annual reports. The Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) report covers a broad range of ESG themes.

[3] Robert Bishop, “Investor Communication and Say-on-Pay Investor Communication and Say-on-Pay,” Yale Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Dissertations, 2021.