Top 10 Equity Compensation Issues for 2025

It’s a new year, there’s a new administration in Washington (including a new SEC chair), and a flurry of regulation is sitting in the rear-view mirror. Uncertainty blankets the road ahead.

We’ll discuss 10 major issues in today’s world of equity and executive compensation, answering three questions for each about what could change in 2025 and beyond. On most topics, we have a clear outlook and point of view, but on some the political and macroeconomic fog of war is simply too high to venture a gander—and that itself is important to identify and unpack.

1. Clawbacks

2. Grant Practices

3. ESG and DEI in Compensation

4. Proxy Advisor Regulation

5. New Award Designs

6. Preparation for ASU 2024-03

7. Updates in Pay vs. Performance Data

8. Tax Policy and Equity Compensation

9. Goal-Setting Process and Disclosure

10. Goal-Setting Uncertainty

1. Clawbacks

Last year, in the wake of final Dodd-Frank clawback rules going live, we helped a number of companies deal with clawback cases by reconstructing stock prices and putting together operating plans and playbooks.

Meanwhile, the SEC sent out 13 comment letters related to compliance with the rules. The letters addressed companies that checked the first new 10-K checkbox but then either didn’t check the second one (indicating a recovery analysis was performed) or failed to file a suitable disclosure about the recovery analysis. More broadly, compliance brings a host of complicating issues, from how to recoup pre-tax shares to how to measure a clawback in the context of a TSR or stock price metric.

1a. Does a restatement functionally require a clawback analysis?

Probably, although it’s not obvious.

Many restatements relate to obscure revisions where the effect on compensation is tenuous (e.g., a revision to the income tax provision when the incentive metrics are based on EBITDA formulations). Furthermore, restatements often cause no impact to the aggregate balance sheet or earnings.

Our interpretation of the SEC comment letters is that if a restatement happens, the SEC will expect a formal recovery analysis, with conclusions disclosed in reasonable detail.

1b. Will best practices for enforcement logistics emerge?

Yes.

Myriad logistics arise while activating a Dodd-Frank clawback. Some are spelled out in the final rule, like what the recovery amount has to be (answer: the pre-tax erroneously awarded compensation) and what must be disclosed in the proxy. However, there are other junctures—think recovery method, use of exemptions, treatment of stock price and TSR metrics, and application of the rule to foreign private issuers (FPIs)—where the right direction isn’t so clear.

One thought is that granted, but unvested, awards are inappropriate to use as a recovery method. There’s also chatter that the bar should be extremely high for applying any of the three exemptions, including the impracticability exemption. We don’t expect a standardized way to calculate recovery amounts on TSR or stock price metrics. But there are reasonable and unreasonable techniques to use in different fact patterns, which will be important in bulletproofing these analyses from allegations of opportunism or lack of rigor.

Best practices will be a challenge to develop for FPIs because they don’t even have a bright line for basics like determining who is an executive officer. Either we’ll see a convergence of methodology or the SEC will simply accept any good faith effort toward compliance.

1c. Will companies without voluntary clawbacks adopt them?

Yes.

Most large companies already have voluntary clawbacks that operate outside the Dodd-Frank framework. Proxy advisors and institutional investors are pushing for clawback policies that may affect even time-based awards and are triggered by non-financial matters like excessive risk-taking and reputational harm.

A bigger unknown is how often they’ll be activated. While these voluntary clawbacks are broader in scope, they give the board of directors discretion on when to use them.

2. Grant Practices

The SEC has released two rules impacting spring-loaded and bullet-dodging grants. One is SAB 120, which became effective on November 24, 2021. The other is a new Item 402(x) table and narrative disclosure, effective for fiscal years beginning on or after April 1, 2023. The Gensler SEC was plainly concerned with managerial opportunism and the risk of a “backdating 2.0” phenomenon.

So far, there have been a few Item 402(x) disclosures and no public valuation revisions linked to SAB 120 (though it’s possible that some have been reflected in financials without being separately highlighted by the company). However, we’ve seen many close calls. The rules extend to ordinary granting even though they were written mostly for situations like the well-known (and extreme) Kodak case. That makes this a sleeper issue that could end poorly if misunderstood, so granting practices in general are worth revisiting.

2a. Will granting policies continue to be designed for consistency or will they be adjusted to de-risk against triggering a SAB 120 and Item 402(x) issue?

Unsure.

Pre-specified fixed dates deliver consistency, transparency, and objectivity. In an investigation, they support the defense that the grant timing couldn’t have been manipulated because the date was hardwired a year in advance—long before anyone could have known whether the earnings release would be positive or negative.

However, even this theory has limitations and may not operate as an unequivocal defense. Companies often have discretion on when to release or set up accruals, settle litigation, impair goodwill or intangible assets, and so on. A grant may have been planned a year before an earnings release, but that doesn’t mean certain decisions couldn’t be made in that specific earnings release to artificially spring load the grant.

Furthermore, pre-specified grants are no bulwark against accusations of manipulation in a discretionary material non-public information (MNPI) release, such as a product, market, or executive entry/exit announcement.

Overall, pre-planned grant timing provides a strong defense against an SEC investigation. Still, the cookie can crumble in such a way as to trigger an Item 402(x) or SAB 120 disclosure. It remains to be seen how interested companies will be in revising longstanding processes to improve the odds of avoiding Item 402(x) and SAB 120-triggering events.

2b. Will pre-planned grants within blackout windows withstand scrutiny?

Unsure.

This is a specific use case that occurs under the umbrella of pre-planned grant timing. Some companies allow equity grants during blackout windows to ensure timely compensation for new hires and promotions, and under the view that grant timing shouldn’t matter if the dates are hardwired in advance.

However, this runs the risk of triggering a SAB 120 adjustment or Item 402(x) disclosure. The risk of a SAB 120 adjustment is particularly high since the focus of the SEC guidance isn’t whether the policies were good, just whether the grant date stock price failed to embed all current public and private information. The risk of a SAB 120 event is also amplified given there aren’t bright-line date separators as there are in Item 402(x).

2c. Will bright-line triggers emerge for SAB 120?

Probably not.

A key difference between SAB 120 and Item 402(x) is that SAB 120 doesn’t have bright-line triggers. There are two important gray areas. First, how many days between the release of MNPI and an equity grant would be sufficient to not merit an adjustment? Item 402(x) clearly specifies a five-day watermark, but SAB 120 is silent. Second, is the bar higher for a SAB 120 adjustment if the award is an ordinary course grant pursuant to a pre-defined granting calendar?

There’s simply not enough in SAB 120 to answer these questions, so absent further guidance from the SEC, it will depend on external auditor institutional practices. To date, we’ve not seen consistent views. Subject to SEC priorities, we think there would be value in supplemental guidance, especially guidance that harmonizes SAB 120 with the bright lines in Item 402(x).

3. ESG and DEI in Compensation

At a corporate level, environmental, social, and governance (ESG) matters play into public relations, hiring, and much more. ESG metrics are also used in many annual and long-term compensation plans. While energy and utilities companies are more likely to use “E” metrics, “S” metrics tend to show up across all sectors. Also, compensation teams often conduct pay equity studies where questions of gender and race arise.

Some say ESG metrics in compensation are an appropriate part of a company’s long-term strategy. Others argue that such metrics reflect flawed priorities and expose the company to litigation risk. We’re not here to take a position on this debate, but we do know it’s become a political football—especially since diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) comprise much of the “S” of ESG.

3a. Will ESG metrics become less prevalent?

Yes.

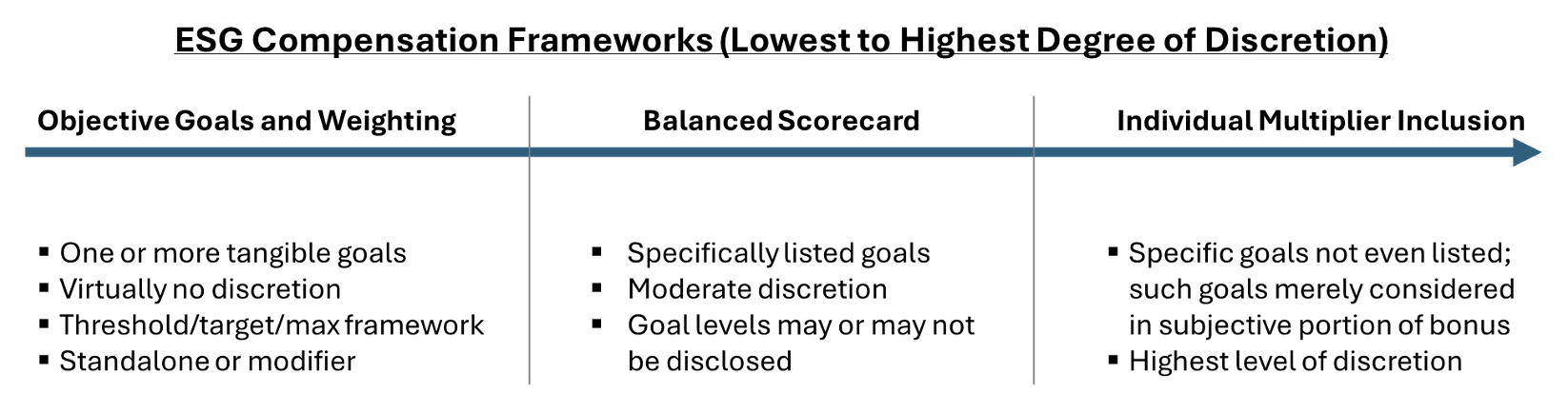

ESG metrics are primarily used in the annual plan where there’s a choice to operationalize them as a standalone metric, as part of a balanced scorecard, or as a truly discretionary part of the subjective component of the annual bonus. On balance, we expect to see fewer objective and standalone ESG-related goals as companies maneuver to the right of the continuum shown below.

3b. Will forward-looking representation (diversity) goals decline?

Yes.

Many companies established and communicated specific DEI-related goals. Now they’re wrestling with whether these could be construed as in-substance quotas.

Forward-looking DEI goals are typically disclosed in three places: the corporate social responsibility report, the 10-K human capital management disclosure, and the proxy Compensation Discussion and Analysis (CD&A) to the extent such goals are used in an incentive plan. The early evidence is that many, but not all, companies are rolling back the use of specific forward-looking DEI targets.

3c. How will the state of the art in pay equity studies evolve?

They’ll become more nuanced.

Total rewards teams conduct pay equity studies to test for statistical evidence of bias due to gender or racial factors. In the past, companies have typically focused on the aggregate company-level adjusted pay gap, as this is what gets reported to senior leadership and potentially even disclosed externally.

However, this figure relies on broad assumptions around how employees are paid across the organization. For example, it assumes that factors like experience and performance affect entry-level roles the same as more senior roles. Leading pay equity studies apply different control factors for each employee cohort to identify outlier employees. This is the same framework used in courts for litigation over fair pay.

Additionally, pay equity studies have traditionally focused on cash compensation only. With the growing magnitude and prevalence of issuing stock-based compensation—particularly among human capital-centric firms in technology, financial services, and healthcare—it’s crucial to start incorporating this pay element in the analysis. Otherwise, the outcome of a pay equity audit may be incomplete or misleading, especially if decisions about the size of stock-based awards are highly discretionary (e.g., negotiated heavily as part of the hiring process, granted on a one-off basis to retain certain employees, etc.).

4. Proxy Advisor Regulation

The regulatory landscape for proxy advisors is more convoluted than ever.

In a win for ISS, a DC district court ruled in 2023 that proxy advisors weren’t engaged in “proxy solicitation.” It appeared efforts to regulate proxy advisors were effectively over. But other legal challenges continued to move through the system, and in 2024, the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit ruled against the SEC’s attempt to roll back the 2020 proxy advisor regulations. Then, just three months later, the Sixth Circuit took the opposite stance, siding with the SEC in favor of the less stringent 2022 rules.

With conflicting decisions at different levels of the judiciary, the situation remains uncertain, especially with new SEC leadership under Paul Atkins. The next steps could involve the Supreme Court settling the dispute or Atkins simply reinstating the 2020 rules and daring legal challengers to oppose him. Alternatively, the SEC may focus its energy elsewhere, leaving the current stalemate intact.

If the 2020 proxy advisor rules are reinstated, they would mark a significant departure from the weakened 2022 framework. The earlier rules imposed stricter requirements, including making it easier to fact-check proxy advisor reports and challenge their assumptions. The “notice-and-awareness” provision required proxy advisors to provide companies with copies of their reports in advance, allow companies to issue rebuttals, and even distribute those rebuttals to proxy advisors’ clients. This effectively gave companies a stronger voice in the proxy advisory process. Additionally, institutional investors were explicitly instructed not to rely on proxy voting guidance without independent analysis.

4a. Will the 2020 proxy advisor rules return?

Probably. The Gensler SEC’s move to water down the 2020 rules was incredibly controversial and the subject of litigation. We wouldn’t be surprised at all if the Atkins SEC reverts to the 2020 rules.

4b. If so, will companies take advantage of them?

Unsure.

The big question is whether companies choose to draft complex rebuttals of proxy advisor opinions under the notice-and-awareness provision. This would be costly and time consuming, with uncertain results, but certain companies may take a stand anyway.

Take Exxon’s 2024 litigation of Arjuna Capital as an example. Exxon didn’t need to litigate the activist given the high likelihood that the shareholder proposal would fail, but the company evidently believed the cost and effort were worth it.

4c. How will award designs trend if the balance of power shifts away from proxy advisors?

More heterogeneity.

Suppose the answer to the prior question is that most companies won’t take advantage of any updated proxy advisor rules, but a few pioneers (like Exxon) will. Then what? The balance of power will certainly shift, but practically speaking, how will executive compensation decision-making and disclosure change?

One possibility is greater diversity in award design. Many controversial executive compensation decisions are deferred due to concern about how proxy advisors will react. If the overall influence proxy advisors wield over institutional investors declines, then (all else equal) we’d expect to see more customization in executive compensation. However, any such change would take years to show up in the data.

5. New Award Designs

Every year, new award designs are considered and tested. Some really stick (e.g., using TSR as a modifier and not only as a standalone metric). Others never quite catch on (e.g., capital efficiency metrics like ROIC, which have their uses but never became the panacea some thought they would be).

5a. Will relative total shareholder return (rTSR) remain the most prevalent metric?

We think so. Relative TSR isn’t perfect, but the alignment it creates with shareholders and the hedge it provides against faulty goal setting have earned it a spot in most long-term incentive programs (LTIPs). That said, the trend has been toward using a portfolio of metrics, instead of putting every egg into a single metric basket, and this we expect to continue.

5b. Will the long-term, time-based award movement intensify?

Doubtful.

Norges Bank is the central bank of Norway, responsible for (among other things) managing one of the world’s largest sovereign wealth funds. Norges has long argued that performance-based equity is a sham because the goals are manipulable and the performance periods are far too short. Instead, they argue for long-term vesting (e.g., five years or longer), post-vest holding periods, and hold-till-retirement provisions.

While there’s an allure to dismantling performance-based equity programs, basic economics tells us executives would likely demand much more pay if their upside is stripped away and the time to vesting is longer. We’re skeptical that US capital markets are prepared for such a shift. In the words of one executive, “Many will be surprised to see that the cure will turn out to be worse than the disease.”

5c. Will adoption of post-vest hold periods continue to increase?

Yes, albeit slowly.

Over time, we’ve seen more companies adopt post-vest holding periods on awards to executives. Post-vest holding periods are attractive because they signal good governance (which proxy advisors favor) and lower the per-unit award cost so companies can increase the size of their grants.

Another benefit is that post-vest holding periods make it easier to carry out a clawback. That may not resonate with many boards, though, mainly because a clawback would be the least of their immediate concerns in a restatement situation.

Although companies adopting post-vest holding restrictions are still in the minority, look for their numbers to increase at a moderate pace going forward.

6. Preparation for ASU 2024-03

On November 4, 2024, the Financial Accounting Standards Board issued Accounting Standards Update (ASU) 2024-03, which will require companies to present a disaggregated view of their income statement. The ASU will be effective for annual reporting periods beginning after December 15, 2026, so there’s still plenty of time to prepare.

The present-day income statement is structured on a functional basis in that it organizes expenses according to their business purpose. Expenses are bucketed based on the stages in the value chain for generating revenue, from cost of goods sold to research and development to selling and administrative costs (and onward). An alternative presentation allocates expenses into natural categories, such as inventory and manufacturing and labor expense.

More specifically, ASU 2024-03 requires companies to classify each income statement line item as one of six types of natural expense. Two of these expense classifications are related to compensation (one being normal compensation cost and the other being termination-linked compensation charges). This ASU has numerous implications, but for now let’s just look at the compensation side.

6a. Will compensation processes be affected?

Yes.

There are three types of processes to look at. First are calculation processes being performed at the pool level instead of the person and grant level. Some companies, for instance, account for their employee stock purchase plans at a pool level. The same is true with cash plans linked to operational goals. Some companies group termination-linked expense with ordinary course expense. Anything done at the pool level will no longer suffice.

Second, mapping processes will need to be built out further. Once expenses are calculated at the person and grant level, these need to be bumped up against an organizational hierarchy matrix. A translation process moves expenses into granular categories (e.g., cost center) and then into the target categories (i.e., profit-and-loss line items). Granular data at the cost center or division level is helpful for running other analytics. A further complexity for some companies is that expense for a single individual may be split and allocated to multiple cost centers and therefore multiple functions.

Third, forecasting and variance analysis will be impacted. Our hypothesis is that market participants will care immensely about this detailed information on corporate costs structures. If this turns out to be the case, then the following axiom applies: Never share information externally that hasn’t been carefully forecasted and explained at a much more rigorous level internally.

6b. Will markets value the additional granularity into compensation cost?

Probably.

ASU 2024-03 is a result of tremendous market-driven pull. In fact, academic research shows that stock price returns vary based on the velocity of investment in different types of labor costs. For instance, a dollar invested in R&D has a longer tail than a dollar invested in sales expense.

In finance speak, this means investment direction is value-relevant, which is to say it can explain future returns. The research doesn’t suggest companies should invest in R&D—investment should go where it’s needed. Rather, it says that something can be learned about future performance based on where investment velocity is directed today. And that’s just one strand of research. After ASU 2024-03 comes online, there’s bound to be much more.

If market participants are eager to get their hands on disaggregated income statement data, then this new ASU should be treated as more than just a compliance exercise. It’s an opportunity to tell a company’s story about where it invests and why. This story will undoubtedly be compared to stories from other companies in the same industry.

6c. Will companies early-adopt the ASU?

Probably not.

The ASU’s non-compensation dimensions could be complex and may require considerable system rework. The compensation components may also be complex for companies using manual processes or performing pool-level calculations. For our clients, this will be a non-issue as we perform granular calculations. Although none of our clients are contemplating public early adoption, we’re already planning dry runs and looking at additional visualization services to further animate the data.

As soon as possible, we encourage companies to dry run their reporting based on the new disaggregated income statement layout. Besides working out systems kinks, this will present an opportunity to begin crafting the story and anticipating questions. If possible, backtesting and trend analysis of prior years should also be performed to understand how the picture may change over time.

7. Updates in Pay vs. Performance Data

Since the release of its pay vs. performance (PvP) disclosure rule, the SEC has kept up scrutiny of PvP filings. Dozens of SEC comment letters have gone out to companies whose disclosures fell short in some way. Recent turnover in SEC leadership may have left the commission’s enforcement priorities up in the air, but companies are still looking for better ways to manage the calculation, presentation, and disclosure processes.

7a. Will the SEC continue issuing comment letters for incomplete or incorrect PvP disclosures?

Unsure.

A lot remains to be seen about the SEC’s priorities, which makes it tough to forecast behaviors at a macro level. However, we wouldn’t be surprised if we continue to see comment letters that focus on raw compliance matters.

7b. Will investors begin taking advantage of PvP data?

Unsure.

This has been the question everyone’s been asking since 2022 when the rule was first released. PvP disclosures haven’t gone the way of CEO pay ratio, because the PvP disclosure is packed with rich information that’s hard to glean in a standardized way from other tables. Not so with CEO pay ratio, which can be inferred using a free Glassdoor account.

7c. Will company calculation processes continue to evolve?

Yes.

Despite PvP now entering its third year, we continue to add new clients looking to solve two problems. One is automating the calculation from end to end. The other is harnessing the capability to answer probing questions from the board or senior management.

The difficulty with PvP is that it involves relatively more complex calculations that are rooted in accounting but interact with core proxy and human resources data. Data and calculation-rich processes that require coordination across functions tend to be risky, due to either personnel turnover or handoff challenges during busy periods. We see a strong trend toward automation of all the proxy tables, which is fitting since that’s been every accounting officer’s mantra for the 10-K and 10-Q since the inception of Sarbanes-Oxley.

Then there’s the ability to answer probing questions about PvP disclosures. Regardless of where investors settle out, PvP tables are volatile because the calculations are so sensitive to the stock price, grant timing, entry and exit, and many other variables. Therefore, compensation committee members will have questions, even if they’re not particularly fond of the disclosure. PvP processes must be able to produce answers to complex variance queries at a moment’s notice.

8. Tax Policy and Equity Compensation

Taxes are always a tricky subject. Some rules are permanent while others go away after a time. And there’s the constant tension of funding the government without getting in the way of growth.

The new administration has a stated goal of extending tax reforms from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, or TCJA, of 2017. Without any new revenue, this will be challenging. Any new tax legislation is expected to go through the budget reconciliation process, which is subject to the Byrd Rule that prohibits raising the budget beyond 10 years. In fact, that’s why some of the provisions of the original TCJA sunset at the end of 2025.

One of the permanent, revenue-raising provisions of TCJA relates to Section 162(m) of the Internal Revenue Code. No longer is there an exemption of performance-based compensation, and any covered employee will remain covered in future years. The American Rescue Plan Act, or ARPA, is set to further limit compensation deductibility by adding five temporary employees to the list of covered employees each year.

While big questions loom for many areas of tax policy, we expect the changes to 162(m) from both TCJA and ARPA to remain in place. Again, revenue is needed to offset the impact of tax cuts. The base of imports eligible for tariffs isn’t large enough to fill the gap alone. Other areas being discussed are closing the carried interest loophole and increasing the excise tax on net share purchases above the current 1%. For now, let’s focus on the impact of 162(m) and the impending expansion via ARPA.

8a. Will the ARPA expansion impact all companies?

Yes.

For tax years after 2026, the next five highest-paid employees—whether they’re officers or not—will have deductible compensation limited to $1 million. It’s possible that the compensation for newly covered employees won’t exceed the limit. Nevertheless, the rule will apply and a careful analysis with thorough documentation will be expected.

8b. Will existing financial reporting and tax reporting processes for 162(m) be sufficient?

No.

Some enhancements will be required, even if they’re not significant. At the very least, the process of identifying covered employees will need to be expanded. There’s already considerable focus on officer compensation, with data readily available and regularly reviewed. Now, the compensation of every employee in the organization is within scope and subject to review.

Under pre-ARPA rules, most tax departments start by identifying the highest-compensated officers. If cash compensation is expected to exceed $1 million, all estimated and actual tax benefits related to equity compensation can be reduced to zero (assuming the cash compensation is deducted first). If cash compensation is expected to be less than $1 million, an analysis is performed to determine how much equity compensation is deductible.

The ever-changing “next five” covered employees will be harder to identify. Some companies may rely on their existing processes to flag the expected next five employees and limit estimated deductions. However, that’s likely to require employee-specific adjustments later when the actual next five are finalized at the end of the year. For that reason, some companies may choose to apply an overall haircut for the next five employees. That would involve estimating the compensation that won’t be deductible—for example, based on last year’s compensation—and then truing up to the actual list at the end of the year.

8c. Will markets care about the new covered employees?

Probably not.

For most companies, the reduction in deductible compensation should be immaterial to financial performance. One open question is whether the ARPA rules require companies to disclose the names of the next five highest-paid employees. It would seem that disclosure isn’t required based on the following passage from the proposed rule, which distinguishes the disclosure of the top three from the next five:

Because section 162(m)(3)(B) determines the three highest compensated employees based on the total compensation required to be disclosed under the Exchange Act for executive officers, the Treasury Department and the IRS considered using this approach to determine the five highest compensated employees for purposes of section 162(m)(3)(C). These proposed regulations would not adopt this approach because, unlike the statutory text of section 162(m)(3)(B), section 162(m)(3)(C) does not reference compensation disclosure under the Exchange Act.

That said, market participants may be interested to see which employees are captured by the ARPA expansion, and perhaps there will be pressure to disclose who these employees are. It’s too early to say how disclosure practices will specifically evolve.

9. Goal Setting Process and Disclosure

Goal setting is hard and important enough on its own. But the process of goal setting is just as critical and tough to get right.

In a notable update this year, ISS began listing disclosure of forward-looking goals as a key part of its considerations around performance equity programs in the presence of a quantitative pay-performance misalignment. This would represent a huge change for most companies, where financial (non-rTSR) metrics are rarely disclosed due to concerns with competitive intelligence and setting investor expectations.

Even pre-grant, we’ve seen companies run into pitfalls in their internal goal-setting process. Usually this is triggered by the presence of multiple budget scenarios and internal misalignment on how those scenarios are used. For example, if goals are set based on one scenario and awards are accounted for based on another scenario, there’s a recipe for a proxy blowup since disclosures link to the accounting values.

9a. Will companies begin disclosing forward-looking performance stock unit (PSU) goals in their proxy statements?

Yes, but slowly and sparingly.

When we asked this question on our recent State of the Union webcast, most companies (62%) were still unsure, which was unsurprising given how early this push is. Interestingly, more companies than we expected (16%) said they already disclose these goals or are planning to do so. The remaining 22% said they wouldn’t, due to either optics or competitive concerns.

Even among the 16%, we expect that some of these companies grant only rTSR, where the goals are generally not sensitive or controversial.

Still, we expect many companies to disclose forward-looking PSU goals if they expect to find themselves under ISS scrutiny. They’ll want to get their disclosures in good shape. Companies that don’t expect this kind of scrutiny will likely wait and see, so it may be a few years before we see this practice settle into a long-run pattern.

9b. Will companies provide further disclosure around goal rigor?

No, but pressure and scrutiny here will continue to climb.

In the same guidance where ISS pushed for greater transparency around forward-looking goals, the firm cited numerous other red flags for its qualitative analysis. These include poor disclosure of closing-cycle vesting results, poor disclosure of rationale for program or metric changes or adjustments, and non-rigorous goals that don’t appear to strongly motivate outperformance. These factors are especially critical if pay quantum or opportunity is high.

Goal rigor has been a recurring theme with ISS. This year’s guidance updates are another push in that direction. Since it’s more ambiguous than forward-looking goals, we don’t expect a lot of companies to start overhauling their disclosures immediately. But if ISS doubles down on this type of analysis, leading companies will surely add a discussion of rigor to the disclosures in their proxies.

9c. What are some other best practices for internal goal-setting procedures?

Documentation of process and intent.

Every situation differs in the details, and many differ even in the broad strokes. But a pitfall for every goal-setting process is insularity. When goals are set and approved by one group of individuals (like the compensation committee) and then used by another group in a different context (like accounting), a disconnect could happen. Documentation and communication are key to avoiding this disconnect.

Take multiple-budget miscommunication as an example. Many budgets or long-range plans comprise a few scenarios based on different states of nature or sets of assumptions. One of these scenarios—typically, the one considered most probable—will likely be used for setting the goals on a PSU. The board’s determination of this as the most probable scenario must be documented and communicated for downstream stakeholders.

The way this can go awry is that the accounting team will begin accruing expense based on what they understand to be the probable outcome of the performance condition. If they’re making that assumption from a different budget, they won’t be expensing at target—and could be expensing substantially higher. Even if this isn’t material to the company’s income statement, it’s likely very material to the proxy disclosure of that individual’s pay, which must match the accounting value. This is a very difficult bell to un-ring after the fact, so it’s critical to avoid the disconnect in advance with good documentation and communication.

10. Goal Setting Uncertainty

Today’s macroeconomic environment brings uncertainty. New government leadership means changes in policy, tariff, and trade policies in particular will affect certain industries materially. Meanwhile, technological advancements like AI could be very disruptive.

All of this makes setting goals for an LTIP difficult. Three years from now, your company’s market might look similar to today. It could also look worse, better, or altogether different. For many companies, these potential differences would necessitate a different approach to goal setting. But each change in a goal-setting approach gives rise to a new set of questions and risks that must be addressed for a well-functioning PSU program.

10a. What are some implications of macro uncertainty on PSU goal setting?

Plan for even greater outcome variance, which means traditional goal-setting techniques may be ill-suited.

If the range of what might occur is wider, and your normal goal setting assumes a narrower range, then the risk in uncertain periods is a higher likelihood of below-threshold and above-stretch outcomes than you might have anticipated. Staying the course is always an option, but sometimes the risk of negated incentives is too high, and the goal setting needs to change.

There are a few different ways that companies can put different goal-setting approaches in action.

- Widen the range by lowering the threshold and/or raising the stretch goal, even if the target remains consistent

- Use shorter-term goals, such as a series of one-year goals that may be more reasonable to forecast than a cumulative three-year goal

- Maintain some amount of discretion or flexibility in how goals are set or managed (exercise caution; more on this in a bit)

10b. What’s a best practice for companies considering shorter-term goals?

Balance critical accounting differences with shareholder optics and participant incentives.

The first concern is the participant incentive, and making sure the PSUs will do what they’re designed to do. The second is shareholder optics and ensuring the shorter-term goals don’t create a say-on-pay issue. And the third is the accounting treatment, which can differ substantially across slightly different designs.

From a governance and shareholder perspective, the main pitfall to avoid is making the LTIP look like a glorified short-term incentive program. For example, we know that shareholders and proxy advisors prefer three-year goals over one-year goals. At the margin, they prefer a series of three one-year goal periods rather than a single one-year goal, especially if there’s a three-year relative TSR wrapped around the full award. But even this isn’t a slam dunk with proxy advisors. The participant and proxy advisor tradeoffs are real.

From an accounting perspective, the main risk to manage is a delayed accounting grant date. US generally accepted accounting principles require a “mutual understanding of key terms and conditions” in order to have a grant date, and one of these key terms is a known performance goal. If you aren’t setting the year two goal until year two, then the year two tranche doesn’t have an accounting grant date until year two. This has the effect of backloading expense and creating volatility in the proxy disclosure, since the award doesn’t hit the Summary Compensation Table and other proxy tables until it has an accounting grant date. For companies wishing to avoid delayed grant dates, a common design tweak is to set the goals by formula (say, X% above the prior year actual result) so that the mutual understanding exists up front.

To be clear, a delayed accounting grant date isn’t fatal, and many companies have this award design. But it does require thoughtful communication so that shareholders understand where the uneven disclosures are coming from, and the accounting team may need to customize their expense process to get it right. Still, this is a mountain we’ve helped many clients scale.

10c. What’s a best practice for maintaining flexibility in goal measurement?

Keep the flexibility as narrow as possible.

As we noted before, an accounting grant date requires a “mutual understanding of the key terms and conditions” of an award. This is generally achieved when performance goals are set. But if those performance goals have much flexibility or discretion, then they cease to be truly set goals. This negates a mutual understanding, which in turn negates a grant date. A lack of a grant date due to discretionary goals leads to very negative accounting and disclosure consequences, including variable liability accounting for the award’s whole life.

So the narrower the range of flexibility—that is, the more objective you can make the subjectivity—the better your chances of having a grant date and avoiding negative accounting and disclosure outcomes.

Part of this is form, and part of it is substance. In form, use “shall” as much as possible in describing the goals and adjustments. That means avoiding the words “may” and “discretion.” As for substance, aim to make the triggers, adjustments, and intent as objective as possible. For example, even if a given adjustment involves unknowns and therefore can’t be specified in advance, you may be able to make the trigger for such an adjustment objective, and you can spell out that the intent is to keep recipients whole before and after such a triggering event.

Every one of these gray-area cases will be decided based on facts and circumstances in discussion with auditors. But strategies to narrow the scope of flexibility increases the chance of a desirable outcome.