Top 5 Executive Compensation Proxy ‘Gotchas’

As equity compensation programs continue to evolve and increase in complexity, preparing the ever-growing proxy statement becomes a more challenging task. There are countless data points to disclose and intricate calculations, like Pay vs. Performance, that are now permanent fixtures.

Unlike financial reporting disclosures that are subject to external audit and attestation standards, the proxy typically does not receive such scrutiny. This creates underappreciated risk, as the proxy has been growing in complexity and numerical density for two decades and can be a source of liability in a similar capacity to the financial reports (as recent executive compensation lawsuits have shown). Therefore, best-in-class companies have processes for gathering and reviewing proxy information that are as robust as their financial reporting, and they leverage experts across the organization.

With that in mind, we’re here to share the most common stumbling blocks in the proxy and how to avoid them.

Assumptions Made by Management and the Board

As we say often, cross-team alignment is essential during every stage of an equity award’s life. Even a plain vanilla restricted stock unit (RSU) can require significant collaboration among HR, legal, accounting, payroll, and others. The element we want to focus on here is communication between the board of directors and management at the time of grant, specifically for performance awards.

Recall that pure performance-based awards are expensed based on the probable outcome of the performance metric. Most often, the best estimate on the grant date is that payout will be at the target level, or 100%. However, it’s possible for a performance condition to be deemed above or below target at the time of grant. From an expense standpoint, this would result in the value amortized to be scaled up or down to the non-target expectation.

Critically, the same principle governing expense recognition is used to determine the amount recorded in the Summary Compensation Table (SCT). If the probable outcome at the time of grant is the maximum payout percentage—let’s say 200%—the value in the SCT will reflect that multiplier, thereby doubling what was likely anticipated as the value granted.

While this might seem like an easy outcome to avoid, it can slip through the cracks due to asynchronous review or approval of (1) financial forecasts and (2) performance award targets. Essentially, the board approves goals based on one version of the financial outlook, but the version that makes it to the accounting team is different. If the final forecast is higher than the initial plan used to set performance compensation targets, an above-target expected payout could result in a much higher value being reported in the SCT.

To avoid this outcome, we recommend developing clear lines of communication and streamlined documentation around all assumptions during the process of setting performance goals and valuing said grants.

Type III Modifications

Equity award modifications lead to complexity in many areas, including the proxy. We’ll focus on Type III modifications, where quickly learning the underlying rationale can ensure accurate filings.

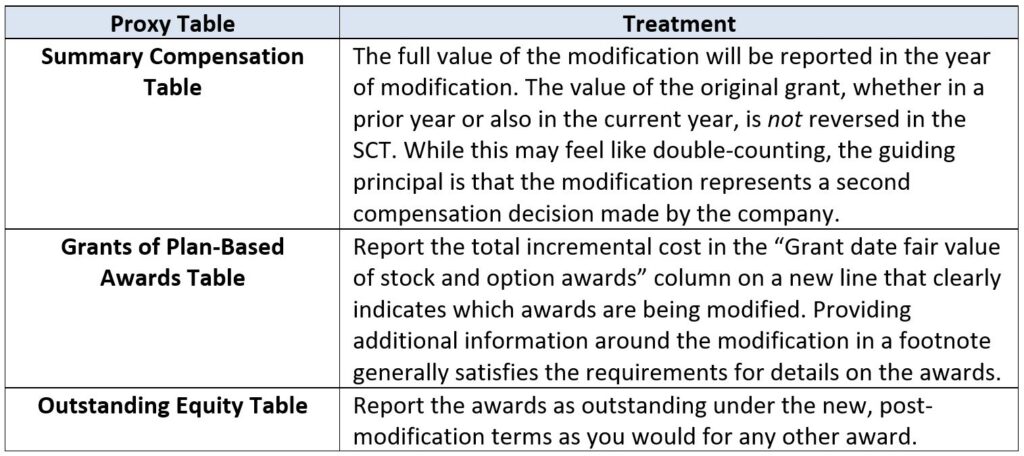

ASC 718 defines a Type III modification as a change to an award’s terms which causes the probability of vesting to switch from improbable to probable. From a financial reporting perspective, the pre-modification award is effectively forfeited (with all prior expense reversed) and the post-modification award is effectively treated as a new grant (with a new fair value). This framework is centered on the value of the original terms being zero due to the improbability of vesting and therefore the full value of the post-modification terms represents the incremental accounting cost to be expensed. The same logic carries over into the proxy statement in several ways:

Note that Type I modifications, where vesting is probable both before and after the modification, may also create incremental cost that would need to be disclosed in the proxy.

Market-Based Award Values in the SCT Footnotes

Let’s turn our attention to the instructions provided in Regulation S-K for the SCT. Specifically, a portion of instruction 3 to Item 402(c)(2)(v) and (vi):

In a footnote to the table, disclose the value of the award at the grant date assuming that the highest level of performance conditions will be achieved if an amount less than the maximum was included in the table.

At first glance, this appears straightforward, and for most performance awards it is. But awards with a market condition (such as relative total shareholder return, or rTSR) can trip companies up. The reason is that ASC 718 requires an award with a market condition to be valued using a Monte Carlo simulation (or similar technique that embeds the substantive characteristics). Often, awards with rTSR conditions have a fair value that represents a premium to the grant-date stock price. This grant-date fair value from the Monte Carlo simulation is then used for expense amortization, and for reporting the grant-date fair value in the SCT.

The key pitfall to avoid is using that Monte Carlo value in the SCT footnote. Given the many intentional alignments between accounting guidance and the proxy statement, it’s easy to mistakenly multiply the accounting fair value by the maximum payout percentage. But the grant-date stock price should be used instead of the accounting fair value because the footnote is concerned with the maximum potential value at grant.

The underlying logic is that for every target share being granted under a relative TSR award, the most it could be worth on the grant date is the product of the grant-date stock price and the maximum payout (not the maximum payout percentage and the Monte Carlo fair value, which itself contemplates the maximum payout and would therefore lead to double-counting). Using the grant-date stock price is consistent with all other share-based awards in the SCT.

Performance Levels in the Outstanding Equity Awards Table

The nuance of performance awards comes up again in the Outstanding Equity Awards Table, specifically around instruction 3 to Item 402(f)(2):

Compute the market value of stock reported in column (h) and equity incentive plan awards of stock reported in column (j) by multiplying the closing market price of the registrant’s stock at the end of the last completed fiscal year by the number of shares or units of stock or the amount of equity incentive plan awards, respectively. The number of shares or units reported in columns (d) or (i), and the payout value reported in column (j), shall be based on achieving threshold performance goals, except that if the previous fiscal year’s performance has exceeded the threshold, the disclosure shall be based on the next higher performance measure (target or maximum) that exceeds the previous fiscal year’s performance. If the award provides only for a single estimated payout, that amount should be reported. If the target amount is not determinable, registrants must provide a representative amount based on the previous fiscal year’s performance.

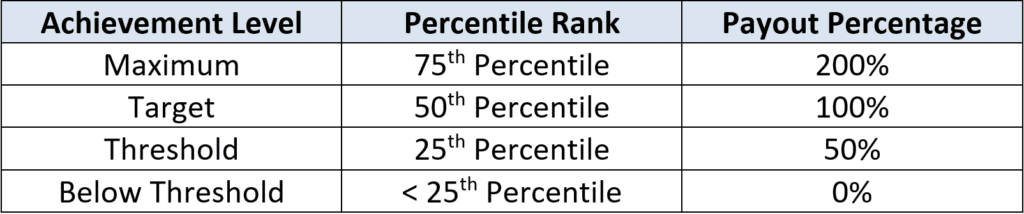

Focusing on the highlighted sentence, the goal is to provide clarity on which payout assumption to use when computing the number of awards (columns (d) and (i) refer to the number of options or stock awards, respectively, displayed in the table) and the market value of the award. In plain terms, we’re told to use a payout assumption one level above the specific award’s tracking at the end of the prior fiscal year. Let’s consider an award with the payout structure below.

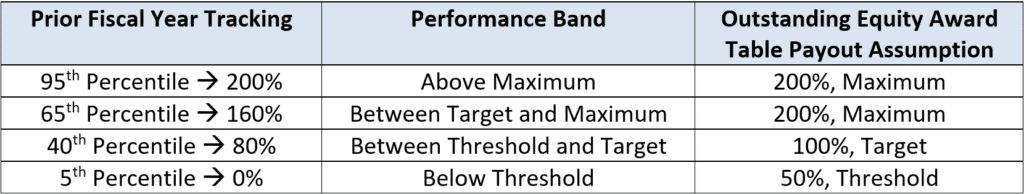

Now, let’s determine how to report this award in a variety of scenarios based on performance tracking at the end of the prior fiscal year.

As you can see, the general rule of thumb here is go one level up. So, when you’re preparing the Outstanding Equity Awards table, be sure to review payout schedules and how the accounting team tracked the award during the prior fiscal year, then go one level up.

Service Inception Date before Grant Date

As noted in ASC 718, the requisite service period for an award usually begins on the grant date. However, there are situations where the beginning of the requisite service period—known as the service inception date—starts before or after the grant date. While rare, it’s important to identify such cases because we’ve seen them handled incorrectly on multiple occasions.

We’ll focus here on service inception dates that precede the grant date, which have definitive conditions provided in ASC 718-10-55-108. When this happens, there are considerations for fair value measurement and financial reporting (as we explain here), as well as the proxy.

While the treatment of awards in both the SCT and Grants of Plan-Based Awards is generally linked to the award’s accounting grant date, the SEC has provided explicit guidance that awards where the service inception date precedes the grant date also need to be reported. The following is Question 119.24 from CD&Is issued in March 2010.

Question: In 2010, a company grants an executive officer an equity incentive plan award with a three-year performance period that begins in 2010. The equity incentive plan allows the compensation committee to exercise its discretion to reduce the amount earned pursuant to the award, consistent with Section 162(m) of the Internal Revenue Code. Under FASB ASC Topic 718, the fact that the compensation committee has the right to exercise “negative” discretion may cause, in certain circumstances, the grant date of the award to be deferred until the end of the three-year performance period, after the compensation committee has determined whether to exercise its negative discretion. If so, when and how should this award be reported in the Summary Compensation Table and Grants of Plan-Based Awards Table? In what year should this award be included in total compensation for purposes of determining if the executive officer is a named executive officer?

Answer: Use of grant date fair value reporting in Item 402 generally assumes that, as stated in FASB ASC Topic 718, “[t]he service inception date usually is the grant date.” The service inception date may precede the grant date, however, if the equity incentive plan award is authorized but service begins before a mutual understanding of the key terms and conditions is reached. In a situation in which the compensation committee’s right to exercise “negative” discretion may preclude, in certain circumstances, a grant date for the award during the year in which the compensation committee communicated the terms of the award and performance targets to the executive officer and in which the service inception date begins, the award should be reported in the Summary Compensation Table and Grants of Plan-Based Awards Table as compensation for the year in which the service inception date begins. Notwithstanding the accounting treatment for the award, reporting the award in this manner better reflects the compensation committee’s decisions with respect to the award. The amount reported in both tables should be the fair value of the award at the service inception date, based upon the then-probable outcome of the performance conditions. This same amount should be included in total compensation for purposes of determining whether the executive officer is a named executive officer for the year in which the service inception date occurs. [Mar. 1, 2010]

While the specific question is based on a fairly unique situation, the highlighted portions are clear that awards with a service inception date preceding the formal accounting grant date should receive the same treatment they would receive if the two dates were aligned.

Ultimately, the SCT and Grants of Plan-Based Awards Table should leverage valuation assumptions as of the service inception date (rather the accounting grant date or an interim financial reporting period end date). Consistent with our earlier pitfall about performance levels being disclosed, this includes assessing the expected performance outcome on the service inception date.

Worth noting, this C&DI also confirms that any awards with a service inception date preceding the grant date should be considered when determining who the named executive officers (NEOs) are for a given year.

Wrap-Up

There are a considerable number of details to get right when it comes to reporting equity awards in the proxy statement. Market and performance-based awards in particular carry unique and sometimes counterintuitive disclosure requirements. If you’re unsure about how to report a specific set of circumstances in the proxy, please don’t hesitate to reach out.