Unintended Consequences of ESPP Design Changes

Over the years, we’ve had the opportunity to help many companies design or modify their employee stock purchase plans (ESPPs). We’ve reviewed and modeled different ESPP features in order to determine the accounting cost versus employee benefit, an analysis necessary to thoughtful design decisions. While there generally aren’t black-and-white answers associated with this analysis, we’ll often back-test to see what the results of plan features would have looked like in the past to help with this cost-benefit analysis. We’ve talked about lookback and reset/rollover features before, so for this analysis we’ll get into some other levers available within an ESPP plan.

For this article, we picked five scenarios from actual client situations that led to surprising, or at least not obvious, accounting results.

Scenario 1: Adjusting the maximum allowed contribution percentage

Company ABC wanted to test the effect of the maximum contribution percentage in their plan. ABC is a west coast software company with a six-month lookback, 15% discount ESPP. Their plan contributions were capped at 10% of pay, but they thought increasing that cap would add even more value to their already lucrative plan. They came to us wondering how much increasing this cap would impact expense, so we modeled three different scenarios: a baseline scenario with everyone contributing at their current percentage, everyone contributing an additional 5%, and everyone contributing the new maximum of 15%.

The surprise: Rather than seeing a 33% increase in expense, we saw an increase in annual expense of about 13% in both scenarios compared to the baseline. We also saw a change in the timing of expense, with one quarter actually coming in with about 2% less expense than the baseline scenario and one quarter with an over 30% increase.

The why: The IRS limit allows participants only to accrue the right to purchase stock at a rate of $25,000 per year. With the 15% discount, contribution estimates are capped at $21,250 per calendar year. This particular company’s ESPP enrollment population was composed mainly of employees with high salaries, causing many of the participants to have already reached the IRS limit under the 10% maximum contributions. This meant that increasing the maximum allowed percentage no longer had any effect on the total expense for these employees (given the cap, there was no extra expense value estimated). Also interesting: The timing of the expense was shifting between quarters as employees were using more of their IRS limit in the first purchase, leaving them with less cap space for the second purchase.

Our takeaway: Under a qualified plan, increasing the maximum allowed contribution percentage is an effective way to increase the marketability of your plan with capped effects on expense. When looking at adjusting this design lever, we suggest running a scenario where all employees contribute the maximum amount allowed under the IRS limit to truly test the upper bounds on the expense amounts. Having a plan where employees are allowed to contribute 100% of their paychecks (subject to IRS limitations) may cost less than you think.

We also suggest breaking employee populations into different categories when modeling this scenario. For example, VPs and above may not change at all since they’re most likely to reach the IRS limit, so you’ll want to focus your model on employees more likely to increase their contributions due to a change in maximum contribution percentage.

Scenario 2: Allowing catch-up contributions (otherwise known as cash infusions) in a lookback plan

In this case, Company XYZ wanted to help employees take full advantage of their existing ESPP. So just before the purchase date, they sent an email notifying employees that they were allowed to make a one-time lump-sum contribution to the ESPP in order to reach the maximum allowed amount, separate from the normal payroll deductions they had been making.

The surprise: This change triggered mark-to-market accounting.

The why: Allowing the employees to make a lump-sum contribution made it so that there was not a mutual understanding of the terms of the award on the offering date. Even though there was a lookback feature, the award could no longer be valued on grant date. According to ASC 718-50-55-2 and 55-32, this is a “Type I” plan feature that undermines the mutual understanding of the key terms and conditions, thereby negating the grant date.

Our takeaway: Allowing cash infusions can be a great way to increase employee participation in the plan. However, this will need to be coupled with increased forecast modeling of expense at different stock price and participation scenarios so that the final expense doesn’t come as a surprise.

Scenario 3: Changing an existing plan’s offering period from four six-month purchases to one six-month purchase period

Here, Company A was considering decreasing the cost of their ESPP by moving from a two-year offering period with four six-month purchase periods to a simple six-month offering period.

The surprise: While this will ultimately decrease expense in the long term, there’s an initial acceleration cost that needs to be factored into the decision.

The why: By decreasing the offering length, the company was effectively canceling future purchases in the active offerings. This is known as cancellation without consideration, and the expense on those future purchase periods would need to be accrued and accelerated right away.

Our takeaway: The acceleration of expense required can be significant, and it may take quite a while to recover the cost incurred with this approach. The better option for this company was to start any future new enrollments with the six-month offering length. While this will take longer to transition, it more importantly removed the need to accelerate expense.

When looking at ways to decrease the cost of an ESPP, we recommend at least considering other options—such as limiting the contribution percentage or number of contribution increases allowed—before drastically diminishing the plan upside by decreasing the offering length.

Scenario 4: Increasing a plan with a lookback feature from a six-month offering period to a two-year offering with four six-month purchases

Company X was interested in increasing the offering period from six months to two years as a way to make their ESPP significantly more valuable to employees, especially in a rising stock price environment. In this scenario, employees will still be purchasing shares every six months, but they will get to look back up to two years.

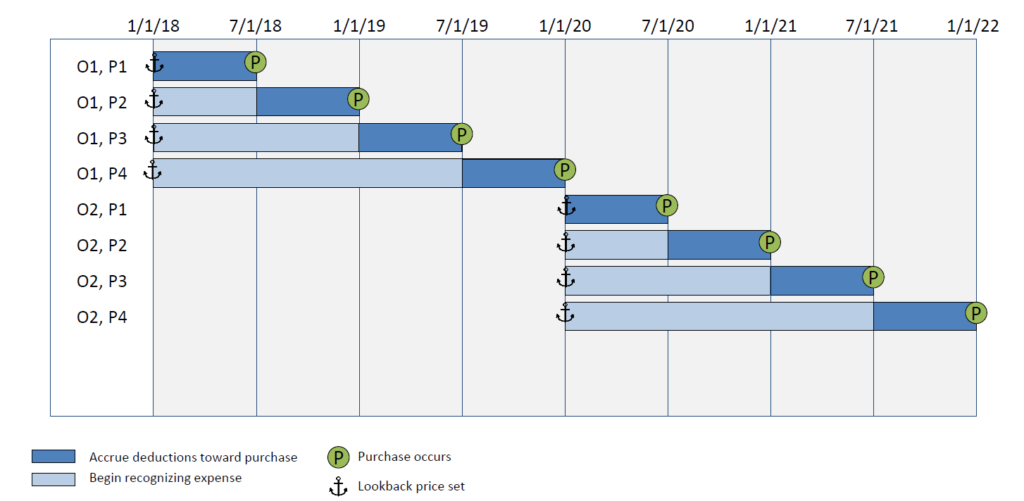

The surprise: It probably isn’t a surprise that your overall ESPP expense will go up when you increase the offering period length. But what can be a surprise is the timing of the expense, in that your ESPP expense will become front-loaded.

The why: Even for companies that use straight-line expense for time-based options and RSUs, graded expense amortization is a best (and common) practice for ESPPs. When you convert the plan, all of the existing employees will be enrolled in one two-year offering. Since all four purchases would start expensing from offering date, you would see a spike in expensing at the beginning of the offering and then less expense towards the end.

(A brief note on why graded amortization is better for ESPPs: It makes handling potential modifications easier. While straight-line amortization can be used, modifications can change the slope of the straight-line amortization calculation and make this method very difficult to get right. Since modifications are especially common in ESPPs, often driven by contribution changes or reset/rollover modifications, it’s important that the reporting process can handle modifications when they occur.)

The figure above illustrates the expensing pattern for a new two-year offering, with all four purchases beginning on enrollment date.

Our takeaway: When completing year-over-year or quarter-over-quarter expense flux analyses, this new two-year cyclical nature of your ESPP expense will need to be factored in. However, we don’t think that this should be a deterrent from offering this type of plan. The additional benefits employees derive from a longer lookback is very cost effective to grant compared to other forms of stock-based compensation. In the steady state following the plan transition, you will have multiple offerings overlapping. Although the expense won’t be perfectly even, it will even out more over time.

Scenario 5: Allowing contribution changes throughout the purchase period

Company Y wanted to asses the impact of allowing unlimited contribution changes throughout the offering period.

The surprise: This added a number of administration and accounting complications due to the need to track each contribution increase and calculate the associated modification accounting.

The why: According to ASC 718-50-55-29, an election by an employee to increase withholding amounts needs to be treated as a plan modification. However, according to ASC 718-50-35-2, any decreases in the withholding amounts are essentially ignored. So when the company allowed unlimited contribution changes, there was a large amount of tracking needed to identify all of the increases, perform a valuation using the stock price on the election change date, and ensure these were all captured in the financial reports.

Our takeaway: One alternative we’ve seen to reduce the additional accounting complexities is to allow unlimited decreases but only allow limited contribution increases—perhaps once per purchase period. However, adding unlimited contribution changes is a great perk and employees may be more willing to participate in the ESPP when they can adjust their election at any time.

For this company, we ended up developing an automated process to identify the contribution increases, perform additional valuations, and determine the associated incremental cost. Since a new valuation could have been required on each day throughout the quarter, a complex manual spreadsheet would have been untenable. We suggest using an automated approach if you would like to add this feature to your plan.

Ultimately, making changes to your ESPP design can be a great way to ensure you’re achieving the goals you established at the outset. But it’s important to have the right data to make informed decisions. This will mean doing some detailed modeling, since the results may not always be intuitive.

We’ve presented these cases so you can see some of the surprising outcomes we’ve run into over the years. If you’re in a similar scenario and you’re not sure where to begin, we’d be happy to help.