CEO Pay Ratio: An Update from the Field

The SEC completed its rule-making for the CEO pay ratio disclosure on August 5, 2015. While we haven’t yet met anyone nominating pay ratio for “proxy improvement area of the year award,” a lot of learning and discovery have happened in the six months since the final standard went live.

We’ve collaborated with companies on the calculation, interacted with industry professionals, and done our own technical and economic research. Here, we report back on what we’ve discovered.

Know the Risk You Want to Manage

We’ve found that companies have extremely diverse risks to manage in their pay ratio disclosure. The top five include:

- Bad press, potentially causing embarrassment for directors

- Internal friction when half the employee population finds out they are paid below the median level

- Stress on internal resources due to the cost and complexity of stringing together disparate data systems

- The calculation being “filed,” not just “furnished,” with the SEC

- The pay ratio fluctuating year over year, leading to general investor inquiry and scrutiny

When we first set out working with companies on pay ratio calculation and disclosure, we mostly focused on the first risk, assuming it was what every company cared about the most. What we found, though, was that concerns differ depending on the specific human capital, demographics, and industry of each organization.

Our recommendation: Socialize the CEO pay ratio disclosure rules with stakeholders and prioritize/rank the different risks. Because the SEC offers broad methodology discretion, knowing what is very important versus less important to your organization can be helpful as you begin to formulate processes and calculation conventions.

Take a Menu-Based Approach

The final SEC ruling offers considerable flexibility in the way companies get to choose the median employee. Any “reasonable measure of compensation” can be used, such as:

- Base salary

- Base salary plus actual bonus

- Base salary plus target bonus

- Base salary plus a bonus measure plus overtime

- Any of the above with or without pension change value

- Any of the above with or without equity compensation grant value

Once the median employee is picked, the pay ratio is computed by running the CEO and median employee selected through the proxy Summary Compensation Table (SCT) framework of compensation. This second component of the process offers much less discretion, so most of the effort centers on selecting the median employee.

At first, we figured the simplest measure (base salary) for identifying the median employee would win 90% of the time. But we discovered something interesting: Simpler measures tend to be more volatile year over year. They yield pay ratios that are overly influenced by outlier records, causing them to be artificially inflated or deflated.

We’re able to test the volatility over time by backtesting the methodology, since most payroll systems contain a full record of all the history. Some of this year-over-year volatility risk is mitigated by the fact that the median employee can be held constant for three years, although even then we still don’t like the risk of volatility when it does become necessary to refresh the median employee calculation.

Further, holding the median employee constant can be another source of noise. If this employee receives an extra bonus in the second year, it will cause a fleeting decline of the ratio that would not have occurred had a new median employee been identified.

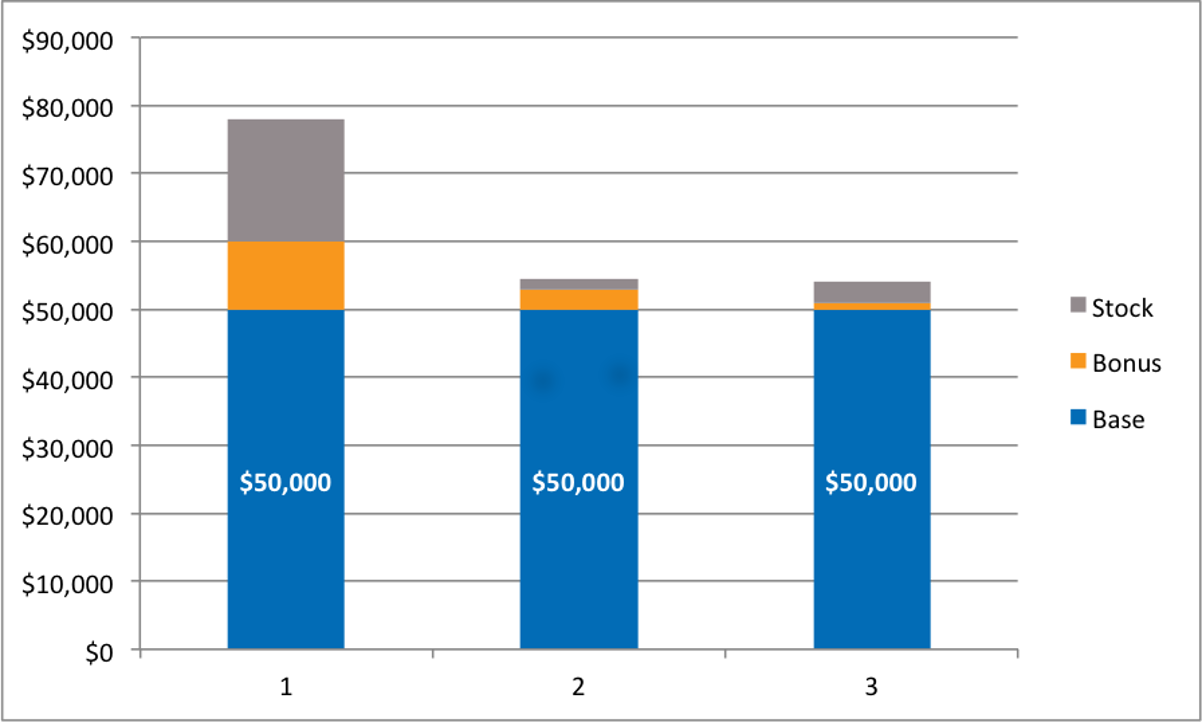

Why would a simpler measure be more susceptible to upward or downward bias? The answer is that the stack of employee data under a simpler measure actually can have two very differently compensated employees next to each other. For example, suppose you have a 1,000-person company. Employees 499 to 501 may all have a base salary of $50,000, suggesting they’re identical. But a fuller measure of compensation may result in employee 501 actually being reclassified down to number 400, employee 500 being reclassified down to number 420, and employee 499 being reclassified up to number 600. In this event, an entirely different employee would be the median, and the final result could be quite different.

In the above illustration, three employees with the same base salary occupy dramatically different places on the pay scale when total compensation is taken into account.

Our recommendation: Model as many different measures of compensation as possible before choosing the median employee. We call this a “menu-based approach,” because each measure of compensation is like a different menu item. Then it becomes much easier to evaluate the incremental costs and benefits of using a fuller or simpler measure of compensation.

Beware the ‘Back of the Envelope’ Measure

Related to the prior point, we’ve been surprised to see many back of the envelope pay ratio calculations turn out to be dead wrong. One such calculation fell from 300 to 200 when done more precisely. Another rose from 600 to 900. An article in the news media ballparked the ratio for one company above 800 and the actual was a little above 500. On the other hand, we’ve seen some ballpark estimates move very little with further refinement.

Our recommendation: Make sure stakeholders know that a ballpark estimate is just that, and is subject to change in the actual pay ratio calculation.

Know Sampling Is Harder Than Not

In an article slated for the April 2016 edition of WorkSpan, we show how hard it is to implement the SEC’s sampling framework. We find that to do sampling right and in a way that’s consistent with the SEC’s economic analysis, sampling may be even harder than using the full population. At the same time, it could yield a less accurate measure.

To do sampling right, the best shortcuts are off the table. We’re talking about excluding individual countries or segments of the population. The 5% exclusion (discussed below) will occasionally be helpful, but is too limited to unlock the intended benefits of sampling.

Additionally, sampling creates risk and difficulty. First, a repeatable process is much harder to automate and document. It takes more effort to document the sampling logic, which you want done to avoid disconnects in future years if sampling yields a much different number. Second, there is residual risk that too small a sample was created, which may cause the pay ratio to bounce around over time and clash with the SEC’s expectation of what constitutes a statistically valid sample.

We found that samples of seemingly manageable sizes (i.e., samples that were easy to create because they bypassed the normal data aggregation challenges) failed to produce results that converge with the results from using the full population. As we increased the sample size, our datasets approached the scope/breadth of the full population, and only then did the calculation results converge.

Thus, the data compilation costs are roughly the same between a full population and sampling approach done correctly. But sampling delivers much less certainty and numerical stability over time. Although we still explore sampling in the projects we do with clients, our sense is that the benefits of sampling are outweighed by the costs, except in unusual circumstances.

Our recommendation: Try to use the full population, especially since you have time. Still unsure? It’s fortunately pretty easy to test whether a sampling approach yields a similar result as the full population. Neither is it hard to simulate what the time savings (if any) would have been had sampling been employed. With this knowledge, you’re in a much better position to recommend a process once pay ratio goes live.

Block and Tackle Your Data

When we first began working on pay ratio issues, we knew it would involve merging and analyzing large datasets. We expected a relatively straightforward process. Large companies maintain payroll information in different and unintegrated systems, but we merge different data files all the time.

But two things surprised us.

The first was obtaining complete data files. Companies that have a single, global payroll system are in good shape. Then there’s everyone else: companies with multiple payroll systems, managed internationally and in a decentralized fashion. They’ve got problems. First, they need active project management to find the data owners internally and clearly specify requirements. Additionally, payroll managers should extract the data, strip personally identifiable information (PII) such as social security numbers or their international equivalents, and send this adjusted dataset. It’s not hard, but it can slow down the process.

The second surprise was resolving data problems and discrepancies. Although many of these problems don’t change the outcome, they’re still worth sorting out so that files tick and tie. Example situations involve:

- Employee mobility

- Rehires and whether their initial IDs have been recycled

- Late-entered terminations

- Illogical values reflecting data entry errors (e.g., salaries of $3,000 instead of $30,000)

The SEC’s requirement to include part-time workers and non-third party contractors is a driving force behind many of these difficulties.

Our recommendation: First, start early and ensure there is an active project management structure. A complete and usable data repository isn’t easy to get. Second, since the pay ratio will be filed with the SEC, calculation accuracy is critical. A lot can go wrong when merging and stacking datasets, so set up a formal review and tie-out process in advance. In short, data management isn’t the main event of the pay ratio calculation, but it does need managing.

Data Privacy and 5% Exclusion

The SEC offered both these provisions to help reduce the cost of compliance. Clients tell us the data privacy exclusion is useless and the 5% exclusion has limited benefit.

According to the data privacy exclusion, companies concerned about violating data privacy laws may appeal for a data privacy exclusion so that they won’t need to transport PII across country lines. The problem is data privacy rules are unlikely to prevent a company from transporting such information within its own systems. More importantly, PII is absolutely irrelevant to the pay ratio calculation: There is simply no reason why social security or other person-specific information is needed.

The 5% exclusion allows the exclusion of countries whose employees collectively make up less than 5% of the employee population. The value of this exception is limited as it tends to only apply to countries with limited operations. Another limitation on this exclusion is that these countries must be excluded completely. Therefore, it can’t apply to single employees, groups, or departments if there are other employees in the same country.

There are, however, some elegant solutions when dealing with tiny countries and difficult-to-extract data. Suppose there are 200 employees in Albania (and suppose further that the 5% exclusion has been exhausted or is off the table for some other reason). If you can prove that all 200 are below the median, then they do not affect the calculation and simply need to be added into the stack of employees without real data.

Our recommendation: Don’t hold your breath in hope of the data privacy and 5% exclusion yielding much simplification; on the other hand, look for elegant solutions when you do run into unexpected calculation roadblocks.

Decide How Much You Want to Disclose

There are two schools of thought about proxy disclosure. One says the disclosure should be as minimalist as possible—maybe just the ratio itself and nothing else. The other says the disclosure should include supplementary information and analysis. Supplementary analysis may include slicing the number by country, full-time versus non-full-time employees, or relating country-specific data to average comparable wages in that country.

We don’t know yet what the practice will be. So far, some companies have committed to the minimalist approach. Others are leaning toward supplementary analytics. Still others intend to run supplementary analytics for internal purposes, but only disclose the bare minimum externally.

Our recommendation: At least run the calculation across different employee segments so you can understand the drivers behind a pay ratio. The effort it takes to do this is so small relative to the insight it gives compensation managers. In general, volunteering supplementary information in the proxy disclosure may be appropriate, but we think it should be done only to address a specific risk or concern.

In Conclusion

At this point, the final pay ratio guidance has been in the public domain for six months and we’ve collaborated with a number of organizations on their reactions and planned methodologies. Many of our predictions were confirmed, such as the data privacy exclusion having a fairly insignificant effect. But we’ve also had some surprises, which we’ve discussed here.

Overall, the CEO pay ratio disclosure is one more step toward a more quantitative and numerically rich proxy. Love it or hate it, the required disclosure has numerous sensitivities tied to it, some of which are relevant internally more than externally. As usual, the best practice is to set up a process before the rule goes live. Since that happens in fiscal year 2017, we suggest that companies run a “dress rehearsal” this year so they can fix any issues and socialize their methodologies in advance of go-live.

Don’t miss another topic! Get insights about HR advisory, financial reporting, and valuation directly via email:

subscribe